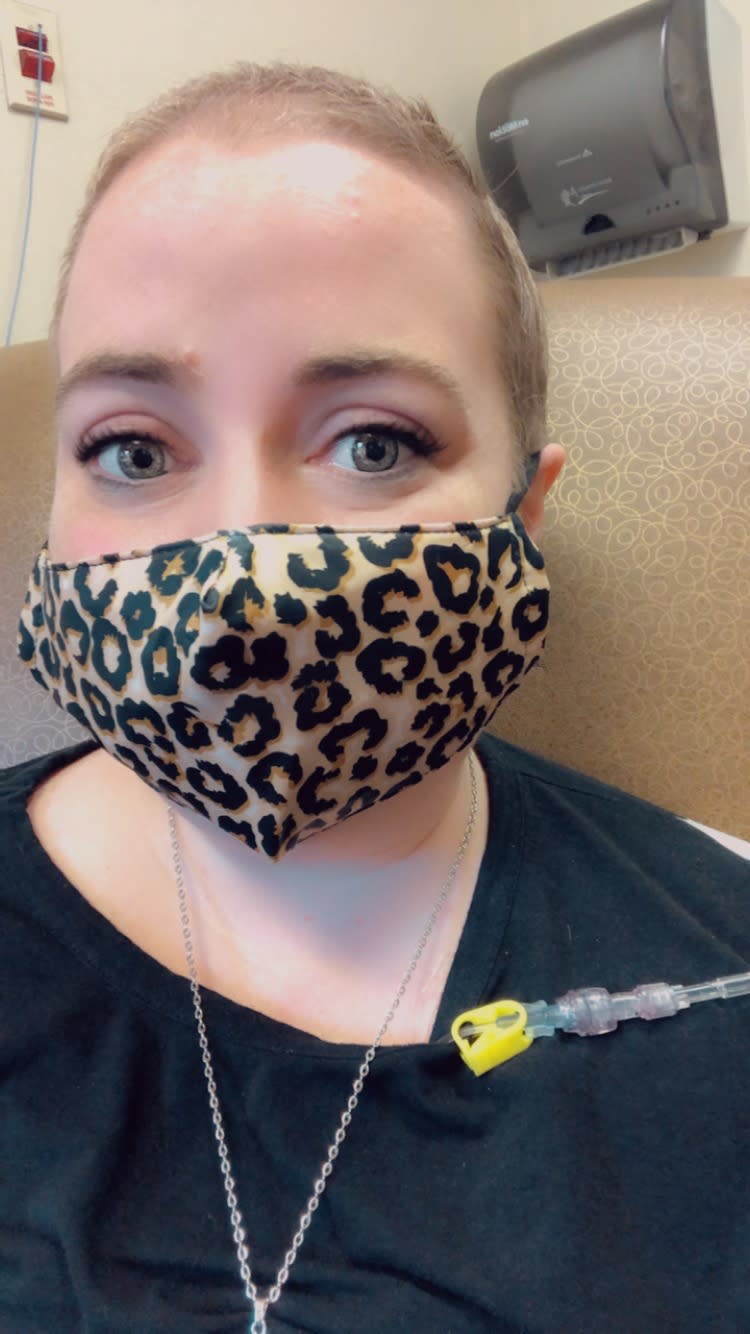

'Am I going to be here in 2 years?': 34-year-old living with stage IV breast cancer grapples with treatment amid pandemic

Over these past seven months, many people have been quelling their anxiety about the coronavirus pandemic by clinging to a belief — that this too shall pass, maybe even in a year or two. But that’s cold comfort for Tori Geib, a 34-year-old Ohioan who has been living with metastatic, or stage IV, breast cancer since 2016.

“There were things I would do before COVID, maybe pushing myself, but I was trying to get experiences — like I had gone to Europe last year and was planning to go back this year for Oktoberfest,” she tells Yahoo Life. But then it was canceled. “Not being able to go and experience what you want to experience when you know you’re on borrowed time … is a gut punch.”

Not to mention, she adds, “You hear, ‘You’re going to have a [COVID-19] vaccine in a year … but with metastatic disease, about 75 people who were diagnosed when I was won’t be alive at the five-year mark. So when I think about a year from now, or two years from now, it’s hard to think about what it will look like and if I will even be here. I had to call the airline and cancel my flight, and they said … ‘You have two years to use your ticket!’ All I could think about was, ‘Am I going to be here in two years to use it?’ That’s not something the average person would think about.”

But Geib is not your average person. At 30, right when her career as a professional chef was soaring, she was experiencing back pain that led her to see a doctor — who noticed something that no one else had from a year-old scan: lesions on her spine and a crushed vertebra. A subsequent biopsy found breast cancer and that it had already spread to her bones and liver.

“I never knew early-stage breast cancer,” she says, explaining that, as a young person, she had also never given any thought to breast cancer, let alone one that could be deadly. Her diagnosis left her in a state of shock and disbelief.

“At first, I didn’t understand the gravity of metastatic breast cancer, because I hadn’t ever heard of metastatic breast cancer,” she says, referring to breast cancer that has returned in or, in Geib’s case, spread to, another part of the body, typically an organ or bones, and is no longer seen as curable.

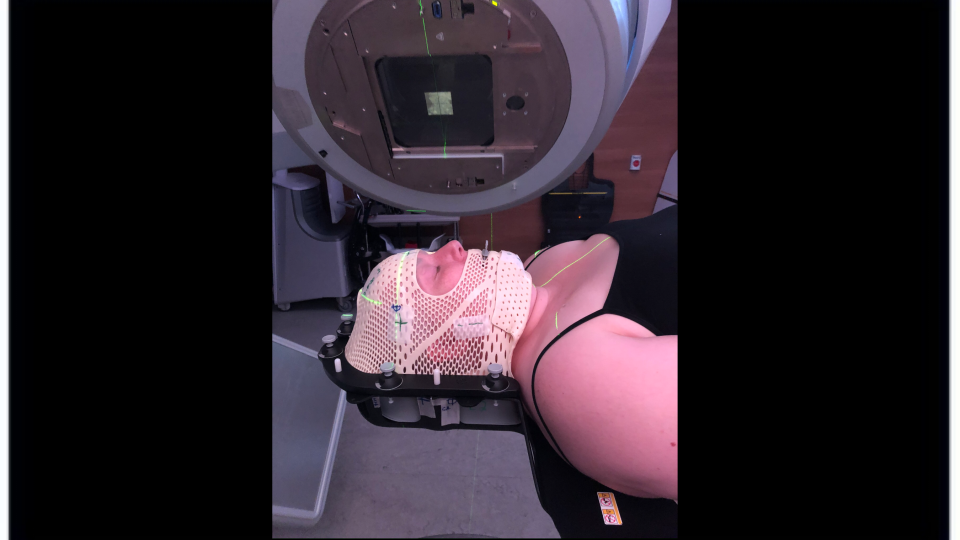

“You see all the success stories with the pink and the celebration, so I thought, obviously these people are OK, why would I worry about this? I didn’t know that people still die of breast cancer,” she recalls, adding that when her oncologist confirmed it was breast cancer detected in her spine, “she said words that will always stick with me — she said, ‘This is no longer curable, but it is treatable.’ I was just, like, what are you talking about? I thought this was a year out of my life — you do the chemo, you do the radiation. It took me a little bit to wrap my head around it.”

Especially as a “de novo patient,” she says, which means someone diagnosed as metastatic from the start (representing 6 to 10 percent of all new breast cancer diagnoses), there was a harsh learning curve. “They typically don’t do breast surgery on those patients,” she says. “So when I was diagnosed and told I was stage IV and that surgery was no longer on the table, that was the first moment I realized that something was really different and that I really didn’t understand this disease the way I thought I did.”

Now, as a full-time breast cancer patient advocate for funding and awareness who has worked with the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, Living Beyond Breast Cancer and More for MBC, she’s striving to help others understand too, including by speaking to Yahoo Life in honor of Breast Cancer Awareness Month and Metastatic Breast Cancer Awareness Day, on Oct. 13. Some of the biggest points she wants to make are that more research is needed, as well as the need for heightened awareness among people of all genders and ages.

“We need to not only be talking about this as an older women’s disease … it also affects young people,” stresses Geib, who is currently on her 11th targeted therapy and who saw her metastasis spread even further, to her brain, in July. “I’ve seen girls as young as 18 with metastatic breast cancer, and while it’s not in the norm, it still is happening. For me, I didn’t know my risk, even though I had a family history of breast cancer, because everyone was in their 50s or 60s when diagnosed.”

Though an estimated 155,000 people are currently living with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in the U.S., 61 percent of people admit to knowing very little about the disease, according to the Metastatic Breast Cancer Network. Still, it’s estimated that 20 to 30 percent of all breast cancer cases will become metastatic, with a median survival rate of three years. Breast cancer is the No. 1 cause of cancer death in women under 50, and, compared with white women, African-American women are diagnosed at a higher rate under age 40 and are more likely to die from breast cancer at every age.

It’s not quite the norm for high-profile celebrities to share metastatic diagnoses, but some, like Shannen Doherty, Bershan Shaw and Olivia Newton-John, have been very forthright — something that Geib appreciates. “I think it absolutely helps when ... celebrities open up about living with stage IV breast cancer in a truthful way, letting people know stage IV is different from early stage, and how,” she says. But the level of helpfulness can decrease, depending on these stories are reported.

A post shared by ShannenDoherty (@theshando) on Sep 30, 2020 at 1:55pm PDT

“I think the media is trying, but you see stories still laced with so many inaccuracies, being afraid to say ‘metastatic’ outright — or … leading their audience to think this person has breast cancer and bone cancer when that’s not the case,” she says, explaining that breast cancer in the bone — or brain or liver or anywhere else — is still breast cancer. Further, she has a strong distaste for the type of “battle language” that often takes over media coverage of breast cancer.

“That, in turn, turns into an unintentional way to blame patients for their success or failure on a treatment. Any time I see an article where it says someone ‘lost their battle,’ it is nails on a chalkboard,” Geib says, echoing the thoughts of many others. “I don’t get why we can’t just acknowledge that breast cancer is a killer, and it’s not about battling or fighting. Doing the treatments for as long as you can is a given. But in a diagnosis where the long-term survival is only 2 to 3 percent, it’s not about ‘winning a battle’ — it’s about facing this every day as long as you can until eventually, the cancer mutates beyond your treatments. That is not a patient’s fault.”

Also not a patient’s fault? The fact that only 2 to 5 percent of all funds raised for breast cancer research goes to studying metastasis.

“Someone dies from breast cancer every 14 minutes. This number has not decreased significantly in nearly 40 years despite a huge movement to raise awareness and funds for breast cancer research,” according to Metavivor, which cites that while more metastasis research is needed, it lacks the necessary funding.

“When you do anything, you want to be successful at it — so if you’re doing something that you’re going to get accolades for … like for early-stage breast cancer, and you’ve figured out how to not have women die when the cancer doesn’t leave the breast,” then that’s what a researcher will want to keep focusing on, Geib says.

“I look at the urgency with COVID, to find a vaccine, and I wish we looked at cancer with the same amount of urgency,” she says. “But the anger isn’t going to help anybody. Making sure research doesn’t stop or stall [because of the pandemic] is critical. Some publications are coming out and saying breast cancer deaths will potentially rise by 10,000 in the U.S., because of the stall in research and clinical trials not being able to happen in the way they need to in order to help patients.” She adds about COVID-19 and breast cancer research, “I don’t think it’s an either-or — I think both need to be studied and that neither needs to take a back seat to the other.”

COVID-19 has affected Geib’s treatment directly too — first by canceling clinical trials that she might have been a candidate for but that, by the time they reopened, she was not because of her brain metastasis (“mets”). Further, it has left her, like so many other breast cancer patients, in all stages of the disease, having to go to treatments and tests all alone.

“With COVID, they’re not letting support people into the building with you,” she says. “I heard I had brain mets in a room by myself. … I had an anaphylactic reaction to one of my chemos, and I was by myself when I lost consciousness. For me, that was really difficult, knowing my mother couldn’t come into the building afterward when I was coming to and scared to death. The way COVID has impacted me and my friends the most has been that [loss of the] support model.”

Despite setbacks, though, Geib is still doing the best she can to look toward the future.

“Long-term survival is only 2 to 3 percent, but you don’t know if you’re going to be that person, or who that person is going to be, and you need to plan on being here,” she says. “There could be a breakthrough tomorrow.”

Read more from Yahoo Life:

How the pandemic has changed breast cancer treatment for women: ‘I went to everything alone’

What to say — and not to say — when a friend tells you, ‘I have breast cancer’

Want lifestyle and wellness news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Life’s newsletter.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports