Marvin Miller is the poster boy for a larger Baseball Hall of Fame dilemma

The Baseball Hall of Fame’s got a Marvin Miller problem.

Every few years, Marvin Miller’s on a Hall of Fame ballot and he’s not elected, and for a day or two there are stories all over the internet about the former executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association not getting elected.

It’s not a huge problem. Baseball fans aren’t going on hunger strikes. Cooperstown’s economy isn’t about to collapse.

It is a problem, though. Nobody wants to read negative stories about themselves, and so it can’t be any fun for the folks who run the Hall of Fame.

You might argue that Miller is just the poster boy for a larger problem: the Hall of Fame’s got a problem with people who made enormous, perhaps revolutionary contributions to baseball, but don’t quite fit into one of the traditional boxes.

The solution? The Hall of Fame should create a Pioneers Committee, which should be composed of credentialed historians with a demonstrated knowledge of baseball history, which would meet every few years with the charge to consider, well, that’s the tricky part.

There’s very little precedent for electing the sort of pioneers we’re talking about. Of the 35 Hall of Famers in the Executive/Pioneer category, only three, all of them from the 19th century, might be categorized largely as pioneers: Candy Cummings, elected for (supposedly) inventing the curveball; Henry Chadwick, for inventing the box score, and baseball reporting generally; and Alexander Cartwright, elected for essentially inventing baseball itself, though his early contributions have been greatly exaggerated for more than a century.

A new committee could address the Cartwright mistake by electing Doc Adams, described by MLB’s official historian John Thorn as “first among the fathers of baseball.”

Adams isn’t the only worthy pioneer. Buck O’Neil’s fans howled in 2006, when 16 men and one woman were elected to the Hall on the strength of their contributions to the old Negro Leagues, but O’Neil wasn’t among them. Even though he was MLB’s first black coach, one of MLB’s first black scouts, and instrumental in the creation of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. O’Neil was, in the words of his biographer, Joe Posnanski, “an African-American voice in baseball when there were very people listening to an African-American.”

In fact, nobody’s been elected as a pioneer, unofficially or otherwise, since before World War II.

Maybe it’s time, again.

There’s certainly no shortage of candidates. Just off the top of my head, in addition to Doc Adams and Buck O’Neil, you could make fine cases for Curt Flood and Lefty O’Doul and Sean Forman.

But there are three pioneers who should be at the top of the list: Marvin Miller, Frank Jobe, and Bill James.

In 1966, Miller took over as executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association.

Before Miller, the players had essentially no substantive rights, and just a small, ill-funded pension program. Within a decade, Miller: supported Curt Flood in his ultimately unsuccessful fight against baseball’s longstanding “reserve clause” that tied a player to his team for as long as it wanted him; guided the players in a 1972 strike that greatly enhanced their pension; and ultimately helped the players achieve freedom of movement for veteran players, which led to huge increases in their compensation.

Not long before Miller died in 2012, super-agent Scott Boras called him up. “I asked him for some time,” Boras said. “I flew to New York and spent two days with him. He told me that to get to the truth of the game, we had to separate ownership from talent. He said, ‘I’m not going to worry about who owns the paintings, but instead about the value of the artist who paints them. The talent of the game is the true attraction. I wanted to make sure the expression is shared in many museums. Not just one.”

St. Louis Cardinals infielder Joe Torre was right in the middle of things, especially in 1972 when the players went on strike for the first time.

“Marvin wanted 100 percent on anything we did,” Torre said. “For instance, when we went on strike in 1972, I was in Dallas for the union meeting, 1st of April. And we were split on when we should go on strike. A lot of the players wanted to put it off for as long as possible. Strike before Opening Day? We didn’t want to do that, and a number of guys voted for the All-Star break. And Marvin just said, ‘Remember, at the All-Star break there will be four first-place teams.’

“I think a big part of Marvin’s success was gaining trust of the players,” Torre added, “and laying out options; he never told players what to do. He was very rational, very easy to understand. I was in negotiating sessions and saw Marvin’s patience in negotiating. I marveled at it. He never changed his tone, and he would always listen. It was a real education for me.”

I’ll admit to being slightly bemused when, in recent months, Tommy John was touted as a deserving Hall of Fame candidate. But not for his pitching. While a fine starter for a long, long time, certainly there’s little separating him from the likes of Jim Kaat and Jamie Moyer. Rather, because he was the first player who underwent ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: Tommy John surgery.

It was revolutionary. But if we’re using Tommy John to tell a story, then why not really tell the story by electing the Hall of Fame’s first doctor?

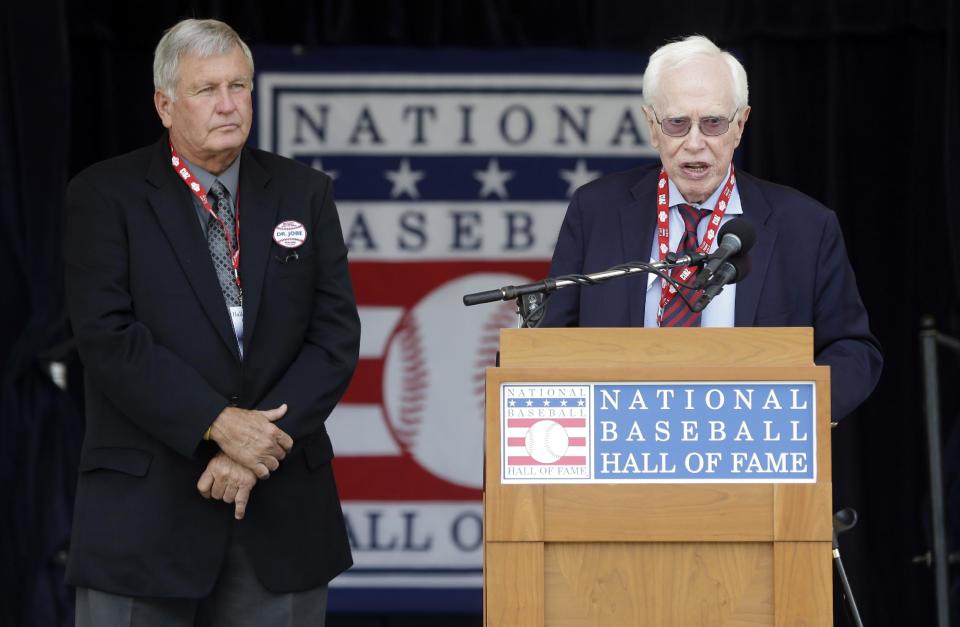

Hardly anybody seems to consider Frank Jobe a serious Hall of Fame candidate — except, it seems, around Dodger Stadium — perhaps because the various committees today simply aren’t tasked with considering anyone who wasn’t a player, manager, or executive. But when one considers just how many hundreds of major-league pitchers have been able to keep pitching only because of modern surgical techniques, wouldn’t it make sense to consider a surgical pioneer?

“Dr. Jobe was a creative genius,” ex-major leaguer hurler and longtime pitching coach Tom House said. “And in addition to being a brilliant surgeon, he had a genius understanding of what might be done to stabilize the joint.”

Yes, if Jobe hadn’t done it, eventually someone else would have. But the same might be said of almost every pioneer, right?

Even Bill James. It’s difficult to imagine 21st century baseball without James, though. When Theo Epstein was still in grade school, he picked up one of James’ “Baseball Abstracts,” and never looked at baseball the same way again. All Epstein has done since is build three World Series-winning teams.

Epstein’s hardly the only baseball executive whose career hinged on James’ early work. Billy Beane’s last year as a player was 1989, after which he went to work for A’s general manager Sandy Alderson, who “almost literally came in and threw every Bill James book at me,” Beane recalled. That winter, he also started listening to James’ nationally syndicated radio show.

“Between listening to the radio show every week and reading the books and being around Sandy, it was quite an education,” Beane said. “At that point, there was just no turning back. Bill literally made order out of chaos.

“And it’s not just baseball. It’s easy to say just baseball, but that’s a myopic view. Bill’s influence transcends baseball, in this world of big data and objective information.”

Does “Moneyball” exist without Bill James? Do the World Series-winning, curse-defying Red Sox and Cubs exist without Bill James? Or for that matter, any of the other data-driven champions in other sports in recent years? Probably not. There would be data-driven champions, of course. But probably not the same ones, and not as data-driven.

But should there really a special place in the Hall itself for the likes of James and Jobe and Miller, and other pioneering figures? Is that necessary to tell the game’s grand history?

“The Hall of Fame gallery is where the game is celebrated,” said National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum president Jeff Idelson. “We’ve got a 50,000-square-foot building, and 90 percent is devoted to history. Which leaves 10 percent for celebrating the great figures who have been elected to the Hall.”

Which is to suggest that the Hall exists largely for the famous figures; the figures people come to Cooperstown to see. But then you think about the owners from the 1920s and ’30s, or some of the more obscure players from the old days. Are they more famous, more worthy of celebration than Marvin Miller, or Bill James? Not today, they’re not.

So let’s imagine a perfect world, in which the Hall of Fame strives, in the coming years, not only to honor the great players of the last 30 or 40 years, but also to tell the story of big-league baseball by celebrating the sport’s most influential figures. Including not only the players and managers and owners and league presidents and commissioners, but also the real pioneers, without whom the game might look quite different than it does today.

“A pioneer award,” Joe Posnanki says, “would add some much-needed life to the thing. The arguments have just gotten so stale. What about the people who made the game more fun? Made the game better?”

Actually, Posnanski prefers the term “contributor” to “pioneer.”

Hey, call it what you like. Just find, somehow, a lasting place for the people who made this great game what it is.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Eagles fan reveals truth behind viral subway video

• Gisele is apparently ‘dead serious’ about Brady retiring

• NFL rejects AMVET’s Super Bowl program ad

• WWE star fired after graphic rape allegation

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports