Kansas City came this close to having a downtown baseball stadium a half century ago

What would it be like to watch the Royals play in a downtown ballpark? Kansas City sports fans might have been enjoying Royals and Chiefs games in a stadium on a downtown hillside for the past half century had things worked out differently the last time the community contemplated where to build a new ballpark.

And because that stadium was originally supposed to have been domed, KC might have hosted a Super Bowl by now — something that hasn’t happened with the NFL skipping roof-less Arrowhead Stadium for “The Big Game” due to our disagreeable climate that time of year.

True, we wound up instead with two classic open-air stadiums that Kansas Citians have every reason to be proud of. The downside for some is that they sit side by side in a sea of concrete 7.6 miles east of the city center with only cars rolling by on I-70, rather than the downtown skyline, serving as a visual distraction from play on the field.

Mostly forgotten now is that Kansas City came close to choosing downtown over the land on which the Harry S. Truman Sports Complex is located. And only those above retirement age will likely remember that the community did not set out to buck national trends by building two sport-specific stadiums.

The goal at first was to build one multi-purpose venue for baseball and football. The only real question was where to put it.

During the 1960s, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Houston, Atlanta, San Diego, New York (Mets and Jets) and Washington, D.C., all had built or were planning to build circular, multi-purpose stadiums. Some were domed. Most were not.

Kansas City was ready to join the parade.

Jackson County officials began their planning in January of 1965 with a goal of replacing the city-owned relic that was Municipal Stadium at 22nd Street and Brooklyn Avenue.

With a capacity of 34,000, Municipal Stadium was too small to suit NFL standards, which set 50,000 seats as the minimum for stadiums as it prepared to merge with the rival American Football League, of which Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt was a founding member.

And Charles O. Finley, then owner of baseball’s Kansas City Athletics, never let anyone forget he thought Muny was a dump. The sight lines were atrocious, as fans’ views were obscured by the many support poles needed to make old Blues Stadium major league ready for when the A’s moved to town in 1955.

Four site finalists

The effort to build modern sports facilities for the teams began in January 1965, when county officials announced that land was available. An unidentified group of business folks had offered to provide for little or no expense land sufficient for a sports complex above an old quarry two miles northwest of where the stadiums now stand.

A meeting was convened at the U-Smile motel, 7901 E. U.S. 40, which included representatives of three top engineering firms. But it wasn’t long before the engineers decided that the Centropolis Crusher Co. quarry was not suitable, and so the site search expanded.

Ultimately, 17 locations were considered, from the stockyards district to the Truman Corners area near Grandview, to Lake Jacomo. Four made the initial cut announced in May 1965:

▪ The land where Municipal Stadium was located.

▪ The former Heart of America Airport and Heart Village trailer park, where Jackson County will soon begin construction of a new jail.

▪ The 350-acre Leeds site, which is where the stadiums eventually ended up.

▪ And a 90-acre site downtown west and south of Municipal Auditorium, roughly where the Kauffman Center now stands and the slope stretching to Southwest Boulevard.

“The engineers did not specifically recommend any one site,” The Star’s sports columnist Joe McGuff would write in recounting the history that led to passage of a June 1967 bond issue to finance construction of the sports complex.

“At that time there was talk of building an exhibition hall, a fieldhouse and tennis and swimming facilities in addition to the domed stadium.”

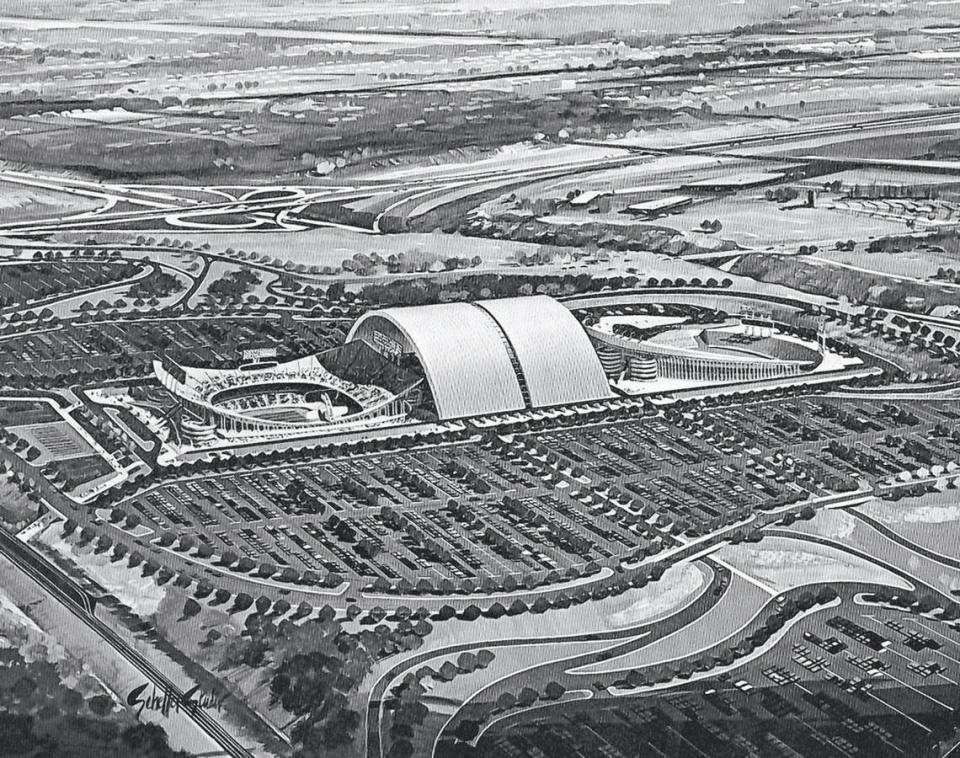

All on the same site. An artist rendition on the May 11, 1965, front page of The Kansas City Times showed how the stadium, arena (fieldhouse) and the rest might all fit alongside each other at the Leeds location.

Downtown and the Leeds site became the two finalists. Over the next year and a half, through the latter half of 1965 and all of 1966, downtown boosters and eastern Jackson County interests fought over which location was more suitable.

Headlined “Downtown, No,” a January 1966 letter to the editor from Robert L. Merrill of Lake Lotawana said it made no sense to replace Municipal Stadium with another facility in an “undesirable neighborhood” and hard to get to by car. Plus, downtown occasionally stunk of the odors rising from the West Bottoms, he noted, although a bit more delicately.

Municipal Stadium’s faults, he wrote, “cannot be corrected by building among the panhandlers and prostitutes in another inaccessible location, with the added distraction of the stockyards and the packing houses,” wrote Merrill, who headed the sports committee of the Jackson County Chamber of Commerce and led the campaign against the downtown site.

Downtown interests argued that the stadium deserved to be in the center of things, citing an engineering report that said the downtown site “has many outstanding qualifications to commend it and holds the possibility of being the most dynamic site.”

But East Jack partisans won, in part, because the downtown stadium would have been more expensive to build due to the price of land and cost of relocating 203 businesses. Also there was far less parking around the downtown location: a projected 7,200 spaces compared to 18,000 at the Leeds site at the time, news reports said.

The choice of where to locate the sports complex was announced in January 1967 at the same time the county said it would go with two open-air stadiums instead of one with a dome.

Why two? The operating costs of a stadium with a permanent roof over it were said to be too expensive and neither the Chiefs nor the Kansas City Athletics wanted to be the prime tenant. Hunt wanted to play in what he hoped would be the best venue to watch football in the nation. A’s owner Charles O. Finley, meanwhile, was insistent on moving his team to either Oakland or Seattle.

With assurances that Major League Baseball would grant Kansas City an expansion team, officials asked voters to approve two stadiums near the junction of interstates 70 and 435 and they did by a comfortable margin.

A rolling roof to cover both stadiums was promised, but cut from the project due to cost overruns.

More than a half century later, the Royals and Chiefs are still playing their games in stadiums that remain classics, whereas only three of the cookie-cutter, multi-purpose stadiums are still standing and only one of those, the Oakland Coliseum, still hosts sporting events as home to the A’s.

Those who wanted a downtown stadium in Kansas City were bitter at first, McGuff reported.

“It was some time before the anger died down,” he wrote in his column in the afternoon paper two days after the vote.

But the desire to have a downtown ballpark never has.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports