Christine and the Queens turned to Angels in America and Madonna to craft his most personal, painful album yet

Chris wants to be it all: a "mother lover," a "generator of electricity," a Nietzschean superman with a goal of nothing less than earthly transcendence. On a recent Paris evening, fresh from a day of rehearsals, the French singer-songwriter talks as if his feet are still a few inches above the floor. "It's very intense right now," he says, before cracking a grin. "It's always fucking me a bit."

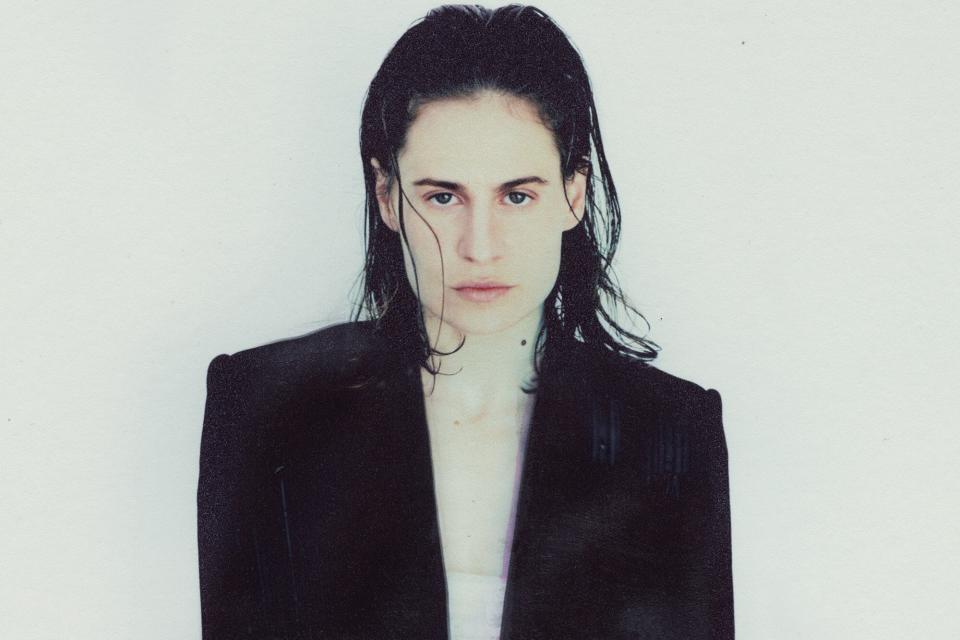

When we speak, Chris — born Héloïse Adelaïde Letissier — is still in his performance garb: pinstripe suit, wet-chic hair, and graphic makeup that evokes tufts of grass sprouting from his eyelids. For his new album, Paranoïa, Angels, True Love — a three-part song suite that stretches his synth-pop to Wagnerian proportions — he is planning a stark, theatrical stage show inspired by Japanese Butoh, the Russian ballet maestro Vaslav Nijinsky, and Western rock greats. "Freddie Mercury!" he shouts. As we speak, he flings his body on the table as if the Queen frontman had crashed through the rafters, and screws up his face in an expression of fear and awe. "Imagine if he just arrived, like, Aargh!"

If there is a constant in Chris' electronic-pop project, Christine and the Queens, it is his desire to never stop changing, like a snake shedding skins. As the romantic dandyism of his 2014 breakout Chaleur Humaine evolved into New Jack Swing–inspired tributes to "horny, hungry, and ambitious" women on 2018's Chris, he has always created a sense that his stylistic shifts and increasingly queer-coded looks went a little deeper than workaday pop reinvention, suggesting a more private project about an identity in flux. In 2019, an unthinkable tragedy struck: Chris' mother died unexpectedly in the days between his two performances at Coachella, leaving him bereft. Grief underscored 2022's Redcar Les Adorables Étoiles, a shimmering prologue to this new record named after the red cars he kept seeing in the wake of her death. Then, before its release, Chris came out as trans in a TikTok video. "I've been a man for a year now — a little more officially in my family and in my relationship," he said. "It is a long process."

Paranoïa, Angels, True Love is Chris' most ambitious undertaking yet, a cinematic journey that, with the help of co-producer Mike Dean, dispenses with pop formulae for luxurious, unruly songwriting, and brings his work closer to the conceptual rock operas of the '70s or the work of art-pop legends like Laurie Anderson. Inspired by Tony Kushner's landmark play Angels in America, particularly the "deep, painful becoming" felt by the central character of Prior, it pinballs from broken-yet-tender catharsis to lusty hedonism, braiding the profane with the divine (with some help from Madonna, who features on three tracks as a godly matriarch). Chris is eager to perform his new material live, and rolls his eyes at the idea of toning down his show for festival audiences this summer. "Mais I would even go bolder," he says. "I'm ready to be a bit surprising."

He is on his way to meet his team for a rehearsal debrief over tapas. But our conversation feels unhurried and warm as he explains his thoughts on working with Madge, what Pride means today, and how he channeled psychological turmoil into an artistic pop spectacle.

Jasa Muller Chris of Christine and the Queens

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: The playwright Tony Kushner has said Angels in America is about "a specific historical moment" with its themes of the AIDS crisis and Reagan-era America. What convinced you that it was time to revisit it?

CHRIS: The conversation around being an outcast in America still burns the same fire [that is] inside all the words of Tony Kushner. Things have evolved slightly, but really the outcasts are still the same. So if you bring back that piece now, it is still very relevant. But what I like about the play is that the conversations are imperfect and raw. The characters are all very layered, good and bad. During lockdown I looked to the Mike Nichols adaptation. I was praying already, and I think the humanity of the piece [meant] I could lay my bones inside of it. It was as deep, fun, and sad, and [like a] Greek tragedy, but with this Jean Genet whip. I needed it to map my brain out.

The record is very raw and was made after the loss of your mother. Was it a part of your grieving process?

The music emulates what happens inside you, especially if the practice is that personal. I was just not ready for where it would take me. The interesting part of this record is that it announced itself from afar. The first song I wrote was "We Have to Be Friends," and I felt almost observed by something wiser. The music just resonated with those deeper dimensions, and it changed me. And there were odd coincidences where it felt like this record was weirdly guided.

You know, going to [producer] Mike Dean's house [in Los Angeles], I had to go past the Archangel Michael Church. He wrote to me at such a weird moment — I didn't know he knew about my work. At the time, I was starting to think of angels as like a sonic sculpture to work on. So everything felt like it was clicking so strangely. The invisible started to fascinate me — how it was acting on things, and how music came from the invisible. But the loss was also heartbreak. It was both grief and heartbreak. So, a double loss.

You improvised many lyrics while in the recording booth. How did that add a new dimension to your music?

This is something that has defined my work. I have often done songs in one take, like "Saint Claude," "Doesn't Matter," and "La Marcheuse." Those songs are precise because I've surrendered. I've been studying Marvin Gaye, especially a song called "Is That Enough." It's a precise unfolding. For this record, I was like, "I want it even more unfiltered and systematic, and I want to just respect this unfolding." The voice you hear on all the songs is the first take.

That's amazing.

The striking thing about this record is that it arrived consistently. Every morning, I woke up at around eight or nine, and I did the song. It was a very intense experience. It shook me up a bit because I wasn't sure what was happening. I felt blessed and a bit terrified because I was like, "What if it never happens again? Or what if it's actually the beginning of something new for me?" I feel like music is a wiser entity than us. It teaches me where to go.

Jasa Muller Chris of Christine and the Queens

Do you feel you've processed the album with more clarity now?

I think in the moment I was clear and lucid as well. I started to circle back on the work of [surrealist filmmaker] Alejandro Jodorowsky and thought of my music more and more as an expression of a subconscious that knows way more.

Madonna plays a character on the record called One Big Eye. Her work here is unusual — outside the box of what featured artists typically do. How did that collaboration work?

I hate boxes. I despite them. [Laughs] But it was super fast. When I was writing the songs in the first takes, a voice started to emerge. I was like, "Who's that character?" I named it Big Eye because some representations of angels depict them with thousands of eyes. I started to find the character very ambivalent. It could be dystopian, a camera like HAL [of 2001: A Space Odyssey]. Or it could be my mom peaking from the other side.

Then I was with Mike one night working on "Angels Crying in My Bed" and I was like, "I should give the lyrics to Madonna." She's a fantastic, clever actress. Mike immediately picked up the phone, and I had to pitch it fast. She was listening on FaceTime, with her piercing blue eyes. I was like, "You need to be this all-encompassing voice in the nothingness of the quantum field. You need to be the mom married with the cyborg. The everything." She was like, "You're crazy. I'll do it."

Do you have any plans to perform the songs together?

I asked her. But then for some reason, it solidified differently as I'm working [in rehearsals]. I think the more bare and bold, the better. I would love to work [more] with her. I would love to paint her one bright color. Maybe all red, like an Archangel Michael iteration, but you can just see her big blue eyes.

Jasa Muller Chris of Christine and the Queens

That would be beautiful. So this is Pride Month. What do you think the purpose of Pride should be today?

You want me to be super blunt?

Yes.

I don't really like the concept of, like, a delineated month. I don't like the fact that we have to stay patient and resilient and take [prejudice] all the [other times]. I would like the pride-ness, the queerness to just be in the conversation. I feel like Pride Month is just a relief of a few weeks. It feels necessary, because it's a place for us to be more exposed and have more speaking [opportunities]. But I want that all the time for us. I want even the question of Pride to be questioned collectively and intersectionally. I would love all these conversations to bleed into each other. I feel like we're scammed by the few things they give us. We are still minorities. We are still fighting for our rights. We are still banned somewhere. We are still threatened with death. So it's a good month, but it's just a small fire. We are the ones that need to blow that flame up.

Has your transness changed how you look back on the way your earlier music explored gender? I think of the "Five Dollars" video, which was inspired by American Gigolo.

Before, I was segmenting a lot. I think the big shift was that I understood how carefully I was being myself on stage. And they were calling it a performance — it was not performance. Have you seen the drag queens that cry during their performance, because this is the only place they feel present in their truth? I felt that for me. And I was explaining it so badly because I was unaware of who I was. My music has always been saying it. That's the beautiful thing about me: I've always been there in my art. So now I see my younger [self] playing with all the tools of my truth, but so unaware of it. I was like, "It's just a game." Oh, no, it was not. [That recognition] saved my life. And now I'm just living my truth everywhere.

Paranoïa, Angels, True Love is out June 9.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free daily newsletter to get breaking TV news, exclusive first looks, recaps, reviews, interviews with your favorite stars, and more.

Related content:

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports