Youth hockey coach speaks out after receiving racist message from parent

Oct. 9 was a normal afternoon as Talha Javaid walked home from the Windsor, Ont., mosque he attends every Friday for congregational prayers. But when the 23-year-old hockey player and youth coach checked his phone, he stopped in his tracks.

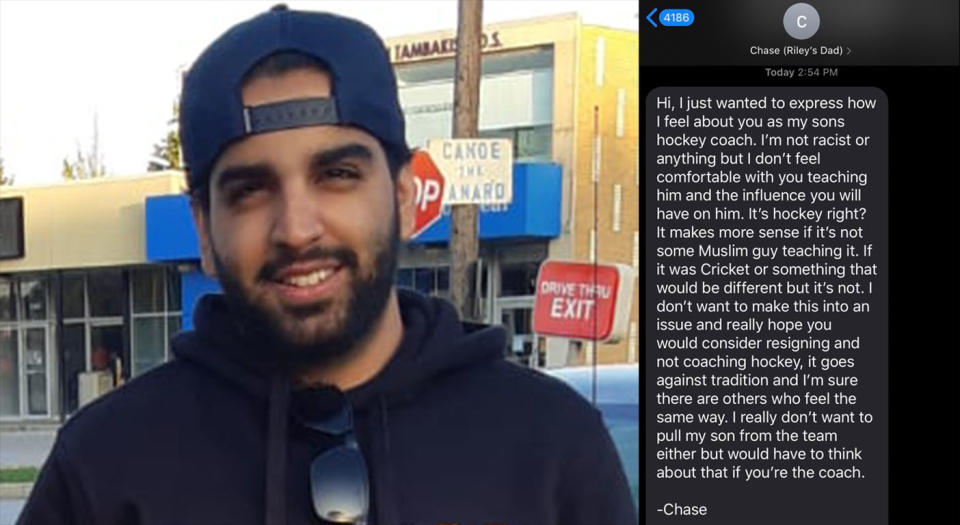

“I was like, ‘What. The. Hell,’” he told Yahoo Sports Canada. Javaid received a text message from one of the parents of a child he coaches. The text message was fully loaded with racist and xenophobic ideology and began with the unoriginal line, “I’m not a racist but…”

man imagine waking up on a friday and essentially being like “yooo, im gonna go be a racist ass muppet today and tell someone they shouldnt coach hockey because they’re not white, cant wait!!” pic.twitter.com/cNYEbsMB8t

— Talha (@flowseidon65) October 11, 2019

Javaid and his best friend Sebastian Nystrom travel to East Lansing, Mich., and pay for ice time out of pocket to provide free clinics and development sessions for players five to eight years of age. His dedication to the sport and to give back to the community was not good enough for one father, identified as Chase, who expressed that he doesn’t “feel comfortable” with his son being coached by a Muslim. Chase was concerned because of the influence Javaid would presumably have on Riley, his child.

In outrageous and ignorant fashion, Chase stated that if Riley was learning how to play cricket, then having Javaid as a coach would be well, more sensical.

Javaid does not, and has never, played cricket.

As a Pakistani-born Canadian Muslim, Javaid is one of the few people of colour in the hockey community in the Windsor-Detroit region. He has played ice hockey and ball hockey since he was a child. Much of his exposure to hockey was from a program at the local mosque called “Fajr Quran Hockey” (FQH) in which young kids go to the mosque for early morning worship and then play ball hockey in the gym downstairs. The Pittsburgh Penguins fan is a full time economics student at the University of Windsor. He volunteers as a hockey coach on weekends. His program has been running for less than a month.

In the text, Chase alluded to the hockey “tradition” that clearly did not include Javaid. He went as far as suggesting that Javaid ought to resign.

“Tradition is coded language for whiteness and the way things have always been,” said Dr. Courtney Szto, assistant professor at the School of Kinesiology and Health Studies at Queen’s University and assistant editor of the Hockey in Society blog. “And a Muslim coach throws a wrench into the whole thing. It doesn’t jive with our dominant narrative of who gets to participate in that culture.”

Javaid said he is overwhelmed by the amount of support he has received and appreciated the solidarity. He noted that his non-PoC friends were aghast and surprised by the incident. Javaid told them he’s used to it — something they found difficult to accept. But the reality is that often when people of colour share their stories, it serves, teaches and educates others with privilege who do not know what it’s like to be on the receiving end of abuse or discrimination.

Javaid’s tweet went viral and he has gotten the support of a few notable players, including Stanley Cup champion and Hall of Fame goalie Grant Fuhr and Minnesota Wild forward JT Brown. Brown, one of the few black players in the NHL, is someone Javaid has looked up to. Brown faced death threats after raising his fist during the Star-Spangled Banner at a game in 2017, in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement and other marginalized people experiencing injustices.

Javaid admits this was not his first encounter with racism in the hockey world — he has dealt with racial abuse and discrimination since he was five years old.

“People think that what happens in the USA doesn’t affect Canada? They’re wrong,” he said. “I remember 9-11, and what happened the next day. I got bullied by older kids at my school. I was five years old.”

And more recently, Javaid has had to endure bigotry from his own bench. “After Trump was elected, one of the guys on my rec team told me he didn’t want a Muslim guy being his captain,” Javaid recalled. “I told him ‘this is a you problem.’ I had the most points on the team and he had like two. I got the playing time I deserved, and I didn’t even bring it up with the coach.”

Javaid said that non-white players often have had to deal with this attitude. There may not be overt forms of racism like the one exemplified by Chase, but there are constant microaggressions that he puts out of his mind.

Javaid has not heard from Chase since the initial text and moving forward, he’s hoping to see Riley at practice despite the interaction with his father. “I want to have as positive of an impact as possible,” he said. “And maybe what I teach him overpowers what his father says about me.” Javaid said that none of the kids participating in the clinics, including Riley, seemed surprised or confused by his presence. They were simply interested in hockey. Other than Chase, the parents have been supportive of the program and the efforts of Javaid and Nystrom.

I would love more non-white and Muslim coaches in hockey because then maybe more hockey kids would grow up to not be racist

— Jashvina ShaAAAAAAAaah 👻 (@icehockeystick) October 12, 2019

Javaid is hopeful that conversations about racism and xenophobia in hockey will help change the toxic culture that does exist in the sport. He does not hesitate to stress that any of the abuse directed at him is worth it if it helps change things. “I don’t care if it’s at my expense. I don’t mind taking the hit,” he emphasized. “I want to help break barriers in hockey. And I’ll know that I helped make it happen.”

Unlearning and uncomfortable conversations are part of the process in white-dominated sports. Dr. Szto agrees that those conversations need to happen.

“We really need to push the narrative that hockey has very diverse and multicultural roots with the Coloured Hockey League and Indigenous contributions so that hockey isn’t so ‘common sense whiteness’ for people like Chase — so to challenge the narrative that hockey is a white man’s game.”

More hockey coverage from Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports