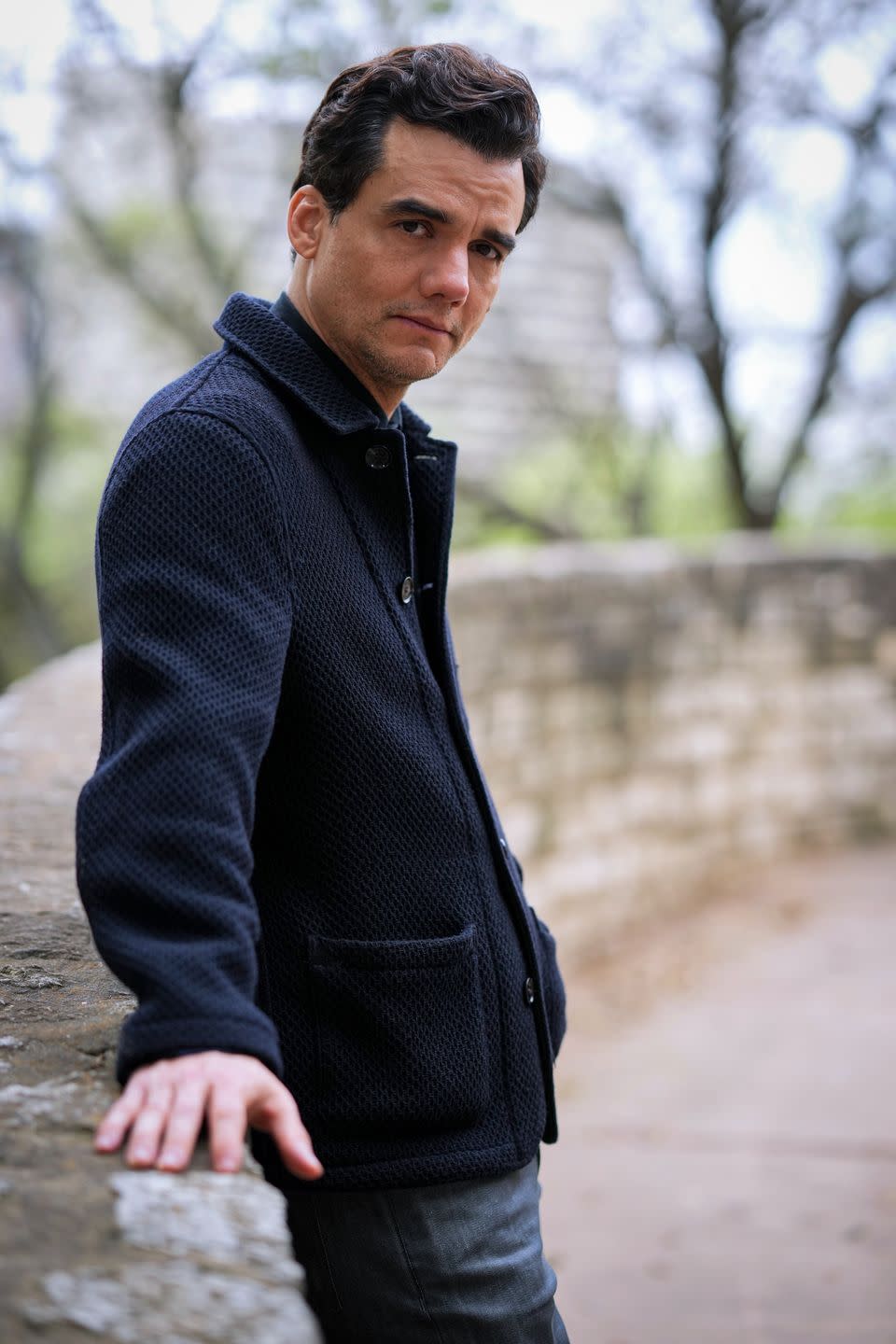

Wagner Moura Is Chasing the Truth

Civil War, the new genre-bending thriller from director Alex Garland—writer and director of meditative sci-fi feats Annihilation, Ex Machina, and Devs—is, at its core, a Very Serious Movie. The film is violent, vengeful, and something of a troubling harbinger of America’s political state. Actor and director Wagner Moura, as a toothsome lead, has famously played some Very Serious Characters—a corrupt police captain (Elite Squad), a potbellied drug lord (Narcos), a mustachioed backstabber (The Gray Man)—with villainous aplomb.

For many, the forty-seven-year-old actor’s face is still synonymous with his forty-pounds-heavier Narcos run, for which he received both critical and popular acclaim and has been irrevocably, delightfully memed. In fact, when Moura recently appeared onscreen on Amazon Prime Video’s Mr. & Mrs. Smith, slimmed, smiling, and wielding an organic juice, one could be forgiven for momentarily wondering, What’s Pablo Escobar doing here?!?

On Zoom (our method of conversation), at least, Moura is quieter and more reserved than his onscreen personas. He weaves from lamenting the despotic politics of Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro one moment to reminiscing fondly about voicing the Big Bad Wolf in Puss in Boots (“a beautiful film”) the next. In Civil War, Moura brings a touch of Big Journalist Energy to the role of weathered reporter Joel, a kind of swagger before the storm, and an antidote to his colleague Lee’s (played by Kirsten Dunst) nihilistic outlook.

At first, Garland’s film drops viewers off for a ride-along in the indeterminate future with four journalists—three grizzled veterans (Moura, Dunst, Stephen McKinley Henderson) and one ingénue (Cailee Spaeny)—bound for the nation’s capital. America, self-destructing in real time, has divided into amorphous but lethal factions in response to an authoritarian federal government, and the muckraking cadre is hoping to score one final interview with the president (Nick Offerman). For a brief period, it seems that what’s to come might veer into reductive satire—which would’ve been slightly too on-the-nose, given the current state of affairs. Instead, Garland’s audience is quickly rocketed into something else entirely. In the span of a single scene, Garland abandons his road-trip movie for a horror-plagued epic—one whose recognizable dimensions proffer a worst-case scenario for America’s hardening political reality.

Ahead of Civil War’s release, Moura talked about life before and after Narcos, the beliefs that fuel his artistry, and the question from Garland’s script that stopped him in his tracks.

ESQUIRE: You originally studied to be a journalist. Did you work as one, too?

WAGNER MOURA: I graduated as a journalist. I worked as a publicist from 1989 to 1990 and for a newspaper in my hometown, in Salvador, Brazil. But I was very disenchanted with journalism back then. When I studied it, I thought I was going to change the world doing investigative pieces. In the beginning, the things that I was assigned to do, the kind of stuff they gave me, it was—

Crap?

Crap. And I was already working as an actor. I started working as an actor when I was fifteen. But to be an actor in Salvador in the nineties, it felt like I wasn’t going to go anywhere. So I studied journalism, and it was amazing. I learned so much. All the things I read were also opening space in my mind for art.

Your career started early, but it feels like Narcos is what brought you global recognition. What was your life like before the show?

It’s a complex question. When we decided to make the move to the U.S. because of Narcos, Brazil was in such bad shape, with Bolsonaro about to become the president. I had just directed [my movie] Marighella, and he kind of boycotted my film and censored it. The way he destroyed mechanisms of culture—it was a dark time.

And then Narcos changed my life in very different ways. People knew who I was. It became a hit in the U.S. It opened up working opportunities that I hadn’t really paid attention to before. And now I live here. My kids live here. Brazil is in better shape, and we’re always asking ourselves if we should go back. The kids don’t want to.

When you did Narcos, did you speak any Spanish yet?

No. It was crazy. I had to learn a full language in order to play a character, which pushed me into it in a very strong way. But it was super hard, super difficult. It’s funny because Brazilians like to think they can speak Spanish. You gotta respect them. They go to Argentina once and it’s like, bue-nos diazzz!

Joel is asked, ‘Where are you from? What kind of American are you?’—that I held my breath when I read it,” says Moura.' expand='' crop='6x4'][/image]

Americans do that, too.

The story with Narcos is that I’d worked with the director [José Padilha] before in this film called Elite Squad, and he was like, “Hey, you’re going to play Pablo Escobar. And I told them you speak Spanish.” Netflix didn’t even know at that point that I was being considered to play the part. So I just threw myself into Medellín—I spent four months there by myself. I went to this Spanish class for foreigners and I was in a class with a group of Japanese teenagers, some German dude, and a few hippies. It was so funny, but it was a great experience.

I was walking around, too, all the time—going to see a soccer game, going to other people’s houses. It was very important to me culturally. Brazilians, we really consume our own culture. We listen to Brazilian music, and we don’t really know the things that our neighbors are doing that are amazing. I remember when I came to know some of the rock ’n’ roll bands from Argentina, like Soda Stereo. I’d say things like, “Soda Stereo is awesome, man,” and everybody was like, “Yeah, of course they are.”

How did you meet Alex Garland?

I met Alex because of Devs. I couldn’t do the role we spoke about then because I was doing this other thing. I was really happy that he remembered me for Civil War. He called me for it; I remember thinking, Oh, this meeting is going well.

He’s a guy who’s very direct. I read the script and felt that there was a perfect film in there for me. I love political movies. My film, Marighella, kind of belongs in that genre. When I see a Costa-Gavras-directed film, or a Gillo Pontecorvo—The Battle of Algiers—I want to follow in the steps of those directors that I admire.

How are you feeling about Civil War right now?

I’m really proud of this one. I knew—I think we all knew—from the beginning that this was going to be no ordinary thing. What I’ve been trying to do as an actor is to find something that’s timely but also interesting for people to engage with. I never liked the idea that in order to do something popular, you have to do something silly. I think Alex got the balance right with Civil War—he’s made a film that’s politically relevant, that captures the so-called zeitgeist, and is interesting for someone who’s just looking to be entertained.

Your character swings between levity in one scene and grief in the next. I’m sure it was difficult to film certain parts of the movie.

There’s one scene in particular—when [my character] Joel is asked, “Where are you from? What kind of American are you?”—that I held my breath when I read it. The way it was written, I had to stop for a moment. That scene really feels like a nightmare to me. I don’t know how I would react to that question in real life. Would I just breathe? Would I be aggressive? Would I respond? I don’t know. I was really, really emotionally distraught filming it, because we ran it so many times. At some point, I was like, “Alex, let’s just finish this.”

I like the fact that Joel lightens things up throughout the movie when they’re all in the car. When I did Narcos, I spoke with so many people that lived in Colombia back in the eighties, when Bogotá was basically the most dangerous city in the world, and everybody was like, “No, dude. We still had a life. We went out, we went places, we went to bars.”

How was it after you wrapped Civil War?

I felt relieved. Civil War was a heavy load. It was an amazing shoot. The fact that we all got along and liked each other—if it wasn’t for that, it was going to be very difficult, because of what we saw in the scenes every day. So much trouble, so much shit.

And it was so loud.

So loud. The volume was a great decision because it really put us in the middle. We were not pretending. We really were affected by the noise, the gunshots. When I went home after that, my body felt a lot. To shake that off afterward, it takes its time. At the end of the day, it was: I need to watch Seinfeld and relax.

Do you want to keep directing?

Yes. I’m going to direct myself in my next project, a film that I’m doing in the U.S. based on the book Last Night at the Lobster, by Stewart O’Nan. I’m working with this great producer on it, Peter Saraf, who did Little Miss Sunshine and Adaptation. He’s someone I really respect. My friend Elisabeth [Moss] is going to make a beautiful cameo in it. It’s this sort of anti-capitalism Christmas movie, but it’s funny, too.

Any chance we’ll see you in another season of Mr. & Mrs. Smith? You were such a charming sociopath.

It’s been a long time since I’ve done comedy, and it was just so fun. I loved it. I hope they have a second season. There was a moment in the last scene where [Maya Erskine] was supposed to shoot me in the head and kill me. And at some point, I was like, “Guys, is there going to be a second season?” And they’re like, “Yeah, man. That’s what we were thinking. But I just think we should kill you.” They kind of shot me in the eye. [Shrugs.]

When you look back at everything you’ve worked on so far, is there anything in particular that really surprised you?

I like to say that movies don’t reflect the process, because I’ve done films where everything was so great, everything was so amazing, the vibe was good, and then you see it and think, Oh. I’ve also had the opposite experience, where the shoot is very chaotic and I’m wondering, My God, what’s going to happen with this thing? But then the movie comes out fantastic.

I try to do things that are meaningful to me, things that I can learn something from. I’m a very political person and I stand up for the things that I believe in. I’ve never done anything for money or for the sense of Oh, this project, people are going to see this, so your career is going to do X. I never care about the thing of Oh, this is going to be a big Hollywood film. If it’s not saying something that matters to me, then I really don’t care. I have to keep doing things that make sense to me, for the person that I want to be, and hope for the best.

You can’t control the risk. You can’t control how people will read you. A movie might be read now that will be read differently ten years from now, depending on how society is organized by the time that thing is being shared. I find that fascinating.

And with Civil War—like I said, I’ve done some things where it hasn’t quite come out as expected. But with this, I’m really proud of it. I’m very happy.

Jacket by Wear London; jeans by Rag & Bone; sneakers by Greats.

Photographs: Jordan Strauss/January Images

Grooming: Michelle Harvey

Styling: Chloe Takayanagi

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports