Uncertainty for college women’s coaches, athletic departments after Roe v. Wade’s reversal

A University of Kentucky athlete who is pregnant is to be educated on “all available options,” so she can make “decisions that she believes are in her best interest.”

Yet nowhere does the athletic department’s current pregnancy policy, published in April 2020, acknowledge that the near-total ban on abortion that now exists in Kentucky might put those two statements at odds. Nor does it offer guidance – for the athlete, her coaches and the people who provide her with medical care – on how to navigate such a fraught contradiction on a decision that could forever alter a young woman’s life.

And it does nothing to address the whiplash speed with which abortion laws throughout the country are changing, with bans lifted one week and put back in place the next.

The Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, one Power Five coach told USA TODAY Sports, is causing “major panic” across women’s college sports.

Athletes, abortion & anxiety: As rights erode, fear for future of women’s sports

This ongoing series is in response to the June 24 ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court case that granted women a constitutional right to an abortion. If you are a current or former athlete, coach or athletic administrator who wants to share your abortion story, please email narmour@usatoday.com or lschnell@usatoday.com.

In the two months since the ruling, referred to as the Dobbs decision, roughly a third of states have banned or restricted access to abortion. In college athletic departments, this has prompted anxiety and concern about what the decision will mean for female athletes and the people their families have trusted to protect them.

Mostly, though, it has created uncertainty. Coaches, athletic administrators and support staff are trying to figure out, often on their own, what is allowed and what isn’t; what they can say and what they can’t; and what they will do if – when – an athlete comes to them and says she needs an abortion.

Kentucky’s ban is in place despite a court challenge. The state also has a constitutional amendment to ban abortion on the November ballot. Asked if the university informed students about these changes or if the athletic department is talking to athletes about them, athletic department spokesman Tony Neely said in an email, “The University has not made a formal campus communication regarding the Dobbs decision, but has communicated with deans and our campus health providers about what Dobbs does and does not do with respect to our practices so they can answer questions and communicate with students accordingly.”

USA TODAY Sports spoke with more than two dozen coaches, former coaches and administrators for this story. Few current coaches were willing to speak openly, some because they don’t want to run afoul of so-called “bounty laws” that allow anyone helping a woman obtain an abortion to be sued.

Many also fear drawing the ire of administrators and boosters, who might not realize athletes have – and will continue having – abortions, or understand how frequently reproductive issues come up within women’s athletics.

“If you played at a top 10 university, you didn't have babies, you won championships," said a former volleyball All-American, whose team won the NCAA title in the 1980s. "Think about that."

Athletes, abortion & anxiety: Women’s professional sports grapple with eroding rights

Avoiding the issue

At a girls basketball tournament in Chicago last month, one coach at a Power Five school physically backed away when asked about the Dobbs decision. Coaches of some top women’s volleyball teams – defending national champion Wisconsin, No. 2 Nebraska, No. 4 Minnesota and No. 13 Florida – declined to comment, as did Keegan Cook, coach of No. 14 Washington and president of the American Volleyball Coaches Association.

Even the CEO of Women Leaders in College Sports, which describes itself as the “premier leadership organization that develops, connects, and advances women working in college sports and beyond,” declined to comment.

“My gut feeling tells me that current coaches, and maybe even athletes, are going to be very reluctant to talk openly about this because they’re concerned about repercussions both from the public and possibly the administration,” said Greg Marsden, who coached the Utah women’s gymnastics team for 40 years until he retired in 2015.

“The Dobbs decision has made this a very difficult situation.”

Young athletes don't typically consider abortion laws when choosing a school, because they don't plan to get pregnant. As someone who worked alongside college women for 40 years, I know it happens more often than you might imagine. 1/4

— Greg Marsden (@UtahMarz) August 7, 2022

Yet it is one that cannot be ignored.

Studies have shown 1 in 4 women will have an abortion during their lifetime and college students, athletes included, are not exempt from that.

“I thought about that a lot in college,” said Kara Goucher, a two-time Olympian who starred at Colorado from 1996 to 2001. “How, if I accidentally got pregnant, I would lose everything. I would lose my opportunity to probably finish college. I would definitely lose my opportunity to run at the collegiate level, which means I'd probably lose my opportunity to run on a professional level.

“It’s like you mess up, sorry, you lose everything.”

According to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research and policy organization, women ages 20-24 accounted for 34% of abortions nationwide, the most of any age group. Women ages 18 and 19 accounted for 8% in 2014, the most recent data available.

And women ages 18 to 24 are at an elevated risk for sexual assault, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network.

That means heterosexual and LGBTQ athletes both face the possibility of unplanned pregnancies. The partners of male athletes, as well.

Marsden, who won 10 national titles and retired as the NCAA’s winningest gymnastics coach, said "a number" of athletes got pregnant during his four-decade career. Some continued their pregnancies while others miscarried, resolving the situation before a choice had to be made.

And some had abortions.

“There’s so much complexity to this, and sometimes it just happens – for a variety of reasons,” Marsden said. “And when it does, it’s an agonizing decision, an agonizing position they’re put in and have to decide for themselves.”

Pressure from patchwork laws

Now some athletes will face the added burden of inaccessibility.

According to Guttmacher, the average cost for abortions at 10 weeks was $550 in 2017, and the median cost for abortions at 20 weeks was $1,670, amounts that can be crippling for poor athletes and those who have to pay out of pocket. The NCAA has a Student Assistance Fund to help cover unexpected expenses for athletes. But that money is doled out by individual schools, so each school decides how it can – and can’t – be spent.

“That gets into a fuzzy area, because the athletic department would be using resources. It's not unlike companies that are doing that, (but) companies doing it is one thing, publicly funded institutions are another,” said Tom McMillen, president and CEO of the LEAD1 Association, which represents athletic directors at the Football Bowl Subdivision.

The funds also will not ease the challenge of getting to a clinic.

Two-thirds of the 38 schools in the SEC, Big Ten and Big 12 are in states with near-total abortion bans or ones where lawmakers are pushing for them. Women in states such as Indiana or Missouri will be able to go across their borders to Illinois or Kansas, but athletes in the deep South will be hundreds of miles, possibly more than a thousand miles, away from the closest abortion clinic.

Even if a student has the money and means to go out of state, there will be privacy concerns. Charli Turner Thorne, the recently retired women’s basketball coach at Arizona State, and others expressed worry about bystanders potentially making assumptions about why a student-athlete misses practices or games.

“Everybody within the institution wants what’s best for the player. I don’t think anybody in your department would turn someone in,” Turner Thorne said. “What it is going to do is make all of this more public. Some of these things have gone on very quietly, to protect the student-athlete. That’s going to be much harder in a red state now, where there’s heightened awareness (of it being illegal). If an athlete disappears for a few days, that can be challenging.”

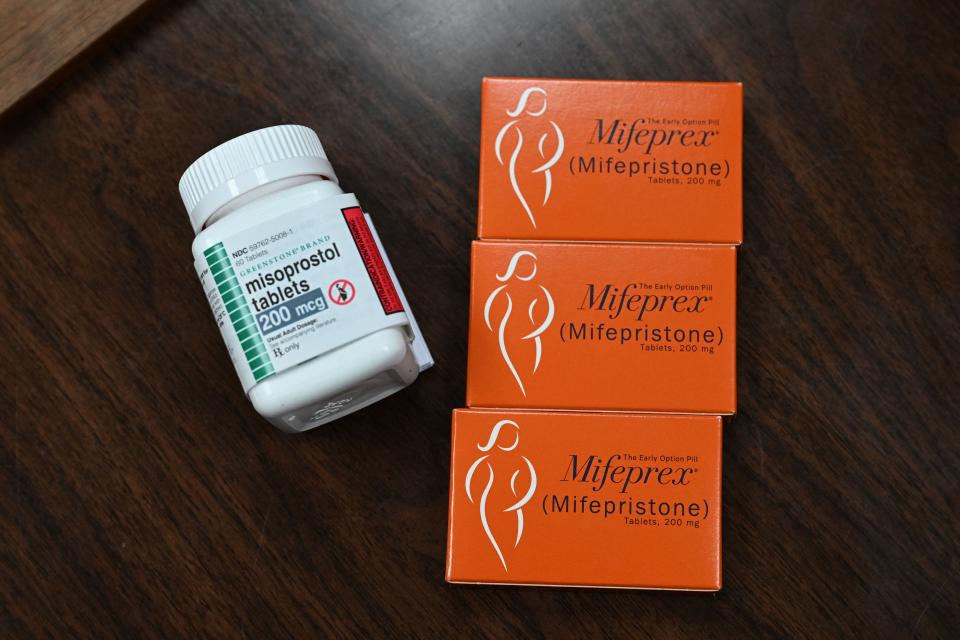

Medical abortion – using the “abortion pill” or Plan C early in pregnancy – accounts for more than 50% of all abortions in the United States. But many states with restrictive abortion laws are targeting that, too.

This state-by-state patchwork of laws creates confusion about a woman’s reproductive rights. Abortion might be permitted in an athlete’s home state, or in states where other conference schools are located, but not in the state where she goes to school.

One coach at a Power Five school in a Southern state said that was the focus of the information their school provided to athletic department officials: how state laws changed after Dobbs, along with a caution surrounding states may differ.

“Pregnancy in college student-athletes is crisis pregnancy,” said Elizabeth Sorensen, who co-wrote the NCAA’s pregnancy handbook, first published in 2008. “It’s a mental health crisis. They don’t know who to turn to for help. They feel tremendous pressure to make a quick decision.”

That pressure can have tragic consequences.

An outdated handbook

In the fall of 2007, a golfer at Bellarmine University in Kentucky and a volleyball player at Mercyhurst College in Pennsylvania were charged with killing their newborns. Both had concealed their pregnancies and given birth in their campus residences. Sorensen, a nurse who was then the faculty athletics representative at Wright State, said she was horrified and vowed to do what she could to ensure no other athlete found herself in such dire circumstances.

Using Title IX’s protections against pregnancy discrimination as the framework, the handbook details the obligations NCAA member schools have to pregnant athletes or athletes whose partners are pregnant.

Pregnant athletes cannot be stripped of their scholarships or kicked off their teams. They must be provided with medical care and granted accommodations if they continue to train. If an athlete chooses to have an abortion, she cannot be retaliated against.

“Schools must treat pregnancy and all related conditions in the same way as they treat any other temporary disability,” the handbook reads. “In other words, pregnant student-athletes are to be treated the same as student-athletes with a knee injury or mononucleosis.”

But the handbook was written when women had a constitutional right to abortion. Since the Dobbs decision in June overturned that right, Sorensen said she has not been contacted by anyone at the NCAA about updating the handbook.

The NCAA has been largely silent on the Dobbs decision and declined to comment after the state of Indiana, where the organization is based, approved a near-total ban on abortions. Nor has the NCAA provided additional recommendations on how athletes will be supported in states that no longer allow abortions.

“If she’s forced to have this baby, what, is the NCAA gonna start having day care available?” Goucher asked.

Many coaches and administrators, to say nothing of players, aren’t even aware the NCAA has a pregnancy handbook.

In a study that will be published this fall in the Journal of Intercollegiate Sport, Sorensen and other health care researchers found most female athletes are in the dark about their Title IX rights and had even less knowledge about resources available to them. Of 146 female athletes at a large Division I school in the Midwest, 90% said they were unaware of the NCAA’s rules on pregnancy, while 98% said they had not received any information from their athletic department.

The handbook encourages schools to come up with their own policies, and many have. But, again, those policies were created before the Dobbs decision, and anyone relying on them now could be running afoul of the law.

Clemson’s pregnancy policy says an athlete’s privacy “will be respected with strict confidentiality,” and provides resources for both adoption and abortion. Yet South Carolina, where Clemson is located, has a law now being appealed that bans abortion once a heartbeat can be detected, at about six weeks, before many women even know they’re pregnant.

Despite Texas having some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the country, Texas A&M’s existing pregnancy policy states the “Athletics Department will strive to provide an environment that respects all pregnancy and parenting decisions.” It also says athletes “cannot be discriminated against because of their parental or marital status, pregnancy, childbirth, false pregnancy, termination of pregnancy, or recovery therefrom” – even though Texas law prohibits abortion in almost all cases.

Texas A&M is in the process of revising the policy, but athletics spokesman Brad Marquardt said it is only to reflect organizational updates, not the changes in Texas law.

“It’s a good policy that speaks for itself,” Marquardt said. “Beyond that, we’re not going to comment.”

‘An ugly place to be’

Athletes aren’t the only ones who will be affected by the Dobbs decision. Texas and Oklahoma have bounty laws offering citizens at least $10,000 to successfully sue anyone who helps a women get an illegal abortion. Other states are considering versions of them.

These could have a chilling effect on anyone associated with a team. It could potentially make it difficult to hire assistant coaches and support staff, such as trainers – often the first people athletes go to for everything from birth control to reproductive care.

“How are you going to get assistant coaches if players come to you and say something and you’re not allowed to help them? I think hiring your staff, that’s going to be your issue,” said Muffet McGraw, the Hall of Fame former women’s basketball coach at Notre Dame.

But even with the threat, McGraw and others said coaches will find ways to help their athletes. They promise parents during recruiting they will take care of their daughters, and Dobbs doesn’t change that.

“If a young woman is in a moment of crisis, that is when they need to know they can rely on us,” said one Power Five coach in a state that bans abortion. “The ruling doesn’t change that it’s our job to support and serve these young women — it’s just made it a lot more challenging.”

Marsden has seen what can happen when women are pushed to the point of desperation. He was in high school and college in Arkansas in the days before Roe and remembers the female classmates who would disappear, some returning the next year with a baby, some without.

Then there were those who did not return at all.

“You had people who were trying to deal with it themselves … and some didn’t survive that,” Marsden said.

“It was an ugly place to be,” he said. “Certainly, by my choosing, we would never look to go back there. Yet, at least in some states, here we are.”

Too soon to know

Emphasizing proper use of birth control to athletes won’t be enough, either.

Birth control can fail. And some states with restrictive abortion laws are also moving to limit access to birth control, emboldened by Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring Dobbs opinion saying that right should be revisited, too.

Some pregnancies wind up not being viable or create significant health risks.

And the harsh reality is not all pregnancies are the result of consensual sex.

In a 2019 survey by the Association of American Universities, almost 26% of female undergraduates and 23% of LGBTQ undergraduates reported nonconsensual sexual contact.

“There's just so many other reasons (to need an abortion), whether it's the health of you as the woman who is pregnant or whether it’s the way that your child was conceived, you know, (if it was) without your permission,” said DiJonai Carrington, who played basketball at Stanford and Baylor before being drafted last year by the Connecticut Sun.

“There's just so many different layers to it.”

Because the Dobbs decision was issued after athletes in the current freshman class committed to schools, it’s too soon to know how far-reaching its impact will be.

It’s possible this will be one more factor athletes weigh when deciding where to go to school, along with coaching staff, playing time, chances to win championships and the prospect of name, image and likeness deals, or NIL. It’s also possible 16- and 17-year-old girls – and their parents – will dismiss a state’s abortion laws as a concern, believing they’ll never be in a position to need reproductive health care.

And with 75% of college students staying in-state for school, according to the American Council on Education, prospective athletes in states with restrictive abortion laws may already have their reproductive rights decided for them.

It’s also possible it will differ by school. The coach at the Power Five school in the Southern state pointed out larger schools have more support staff who can help athletes navigate any situation, while smaller schools won’t have those same resources.

“People will think it’s not going to affect them at first. And then we’ll start to hear these horrible stories, like we did with the 10-year-old,” Goucher said, referring to the Ohio girl who became pregnant as the result of a rape and couldn’t get an abortion there because of the state’s restrictive laws.

“And at that point, people will start to really realize that this is a really, really big deal.”

The team behind the project

Reporting and analysis: Nancy Armour, Lindsay Schnell, Steve Berkowitz, Josh Peter, Chris Bumbaca, Rachel Axon, Emily Olsen

Editing: Alicia DelGallo

Digital design and illustration: Andrea Brunty

Graphics: Jennifer Borresen

Photo editing: Di'Amond Moore

Social media, engagement and promotion: Rachel G. Bowers, Sherlon Christie

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Roe v. Wade reversal breeds uncertainty for college athletic programs

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports