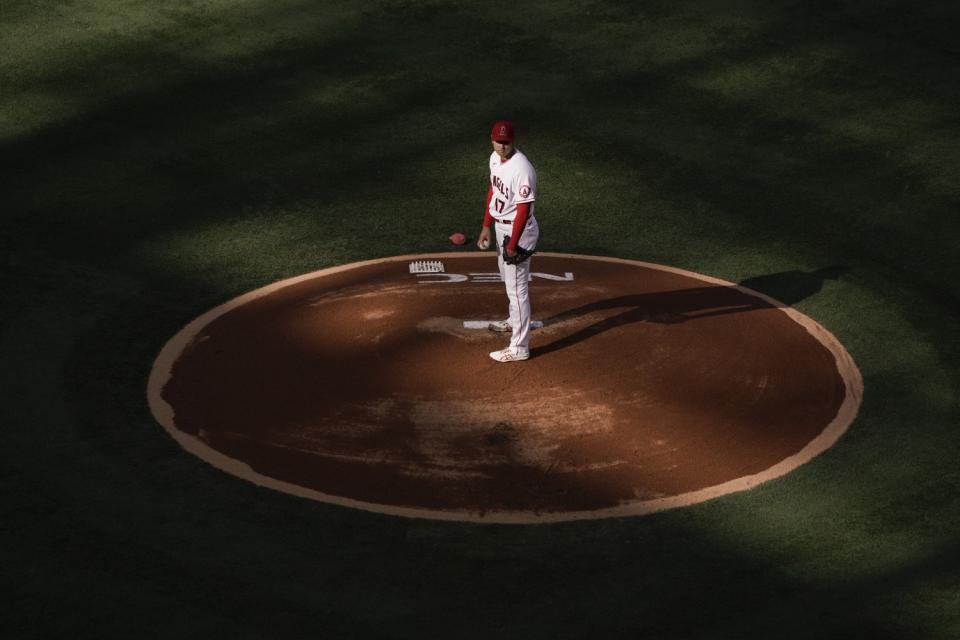

Two-way marvel Shohei Ohtani bypasses superstardom for something larger: Superhero status

His swings are forceful but fluid.

His pitches electric with ease.

For doing something so rare this season, Shohei Ohtani has made his two-way role with the Angels look almost routine.

“It is exceeding what I thought we would see by now,” manager Joe Maddon said. “In both arenas, hitting or pitching.”

There’s no one way to measure the magnitude of Ohtani’s campaign thus far.

As a hitter, he began play Saturday tied for the most home runs in the majors with 14. He leads the majors with 26 extra-base hits, and has a .920 on-base-plus-slugging percentage and 155 wRC+ (an all-encompassing stat in which 100 is considered league average).

As a pitcher, his 2.37 ERA ranks in the top 20 among those with at least 30 innings, while his .152 batting average against and 13.35 strikeouts-per-nine-innings are both sixth-best in MLB.

In Fangraphs’ combined wins-above-replacement leaderboard, his 2.0 WAR ranks sixth in the American League.

And in the wake of teammate Mike Trout’s long-term calf injury, Ohtani now has the best betting odds in the race for American League MVP.

The individual highlights are just as impressive, a reel that grows a little longer almost every night.

He played his first two-way MLB game against the Chicago White Sox during the season’s opening weekend, striking out seven and crushing a long home run. He hit a 440-foot go-ahead home run in the eighth inning against the Houston Astros last month, then an even more dramatic game-winning shot hooked inside the right-field foul pole at Fenway Park to beat the Boston Red Sox last week.

A couple days before that, he golfed an opposite-field home run way over the Green Monster, connecting on a pitch well outside the strike zone. When the Angels returned home this past week, he went deep again on a fastball as high as his chest.

There have been testimonials from current big leaguers and former stars — New York Mets pitcher Marcus Stroman in a tweet called Ohtani “a mythical legend in human form," while former six-time All-Star CC Sabathia declared him “the best baseball player on this planet … ever” — and unwavering praise from his teammates and manager.

It hasn’t been a flawless season — Ohtani missed time on the mound in April with a blister, inexplicably lacked his normal velocity against the Cleveland Indians in his last start, and is striking out as a batter at a career-high 29.5% rate — but it has erased most of the questions and doubts that surrounded his two-way future entering the season.

Three months ago, many wondered if Ohtani’s two-way career would ever come to fruition. Now, he’s one of the sport’s biggest attractions.

“He does not want to be held back,” Maddon said. “I love all of it.”

::

The first time Angels general manager Perry Minasian saw Ohtani in person, Dan Evans was there to witness it.

It was early in Ohtani’s career in Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball league, back when Minasian was the Toronto Blue Jays’ director of professional scouting and Evans, the former general manager of the Dodgers, was the Blue Jays’ top scout for the Asian Pacific Rim region.

Evans had sent Minasian and other club executives plenty of video. But once Minasian laid eyes upon Ohtani, he turned and looked at Evans, who recalled the conversation recently.

“I’ve never seen a guy like this,” Minasian said.

“You may never again,” Evans answered. “But this guy’s for real.”

Minasian’s response: “Oh, I can see it.”

Ohtani’s tools have always been clear.

Evans began following Ohtani since the player’s professional career began as an 18-year-old in 2013 — instantly intrigued upon hearing about a two-way prospect actually interested in pursuing a two-way role.

Evans made several extended visits to Japan each year, coming back more impressed almost every time. Ohtani produced among “the most unbelievable rounds of batting practice I had ever seen,” Evans said. He floated around the base paths and the outfield with a powerful stride and “reckless abandon.”

“I’ve never been so sold on a player, about not only him and his character, but his upside,” Evans said. “I just felt this is a guy who can be a cornerstone of your franchise.”

The question really was whether Ohtani could be a two-way player on a full-time basis. Evans thought so, but not every MLB scout was so sure. Even in Ohtani’s first couple seasons in Japan, he would get regimented off days before and after almost every start, limiting the number of at-bats he got at the plate.

But things changed in 2016. Ohtani got off to a scorching start in both roles, and began hitting more often on the same day he pitched. When a blister forced him to miss a couple months, he flourished as the team’s everyday designated hitter. Once his finger healed late in the season, he became a two-way force in the playoffs, earning the league’s MVP award and helping his team win a Japan Series championship.

“Witnessing it,” said Chris Martin, an Atlanta Braves reliever who was also on the Nippon-Ham Fighters that season, “I was like, ‘Yeah, this guy might be the real deal.’ ”

Like others, Martin was skeptical when he first heard about his two-way teammate.

“A lot of the other foreign guys were like, ‘Hey, we got a guy here that’s two-way. Throws 100 [mph]. Hits 500-foot homers in BP,’ ” Martin recalled. “I’m like, ‘Yeah, right.’ ”

Then, he watched Ohtani hit a leadoff home run in an early July game and pitch eight scoreless innings. When Martin, the team’s closer, hurt his ankle during the playoffs, Ohtani earned the save in the clinching game of their first playoff series, setting an NPB record by hitting almost 102 mph with his fastball.

After serving as the starting pitcher in Game 1 of the Japan Series, Ohtani delivered a walk-off single in the 10th inning of Game 3 — sparking the team’s comeback from a 2-0 deficit in the series.

He finished the season with a .322 batting average, 22 home runs and a 2.12 ERA.

“Watching him in ‘16, it made that season a lot of fun,” Martin said.

And to Evans, it only cemented his belief in Ohtani’s future: “I never had a doubt that he could play seven days a week.”

::

The start lasted just five innings. It included seven walks and only one strikeout. The man on the mound did limit the damage to four runs, and his team went on to win the game too.

But for the roughly 12,000 in attendance at the Polo Grounds on June 13, 1921, this was not the dominant pitching performance they were accustomed to seeing from Babe Ruth.

These days, most conversations about Ohtani inevitably circle back to Ruth, the two-way dynamo who changed baseball and became one of the sport’s biggest legends.

But there are only so many comparisons that can be made between the two, and not just because they played a century apart.

Unlike Ohtani, Ruth wasn’t a two-way player from the start. During the first four years of his career with the Red Sox, he was primarily a pitcher. He hit regularly in an era that predated the designated hitter. But it wasn’t until 1918 that he began to play other positions.

That year, Ruth led the majors with 11 homers and posted a 2.22 ERA in 19 starts. He continued the two-way role through the first half of 1919. But after July of that season, he pitched only three more times for the Red Sox.

Following his trade to the New York Yankees in 1920, he converted to the outfield full-time, making only four starts on the mound the rest of his career as he transformed into MLB’s first 700 home-run-hitter.

“He wanted to transition primarily into a position player,” said Shawn Herne, executive director of the Babe Ruth Birthplace and Museum in Baltimore. “Later on in his life, his daughter told me he was most proud of his pitching records, and he pitched a few times for the Yankees here and there, but not very often."

That game at the Polo Grounds in 1921 was one of the exceptions — an outing that recently became relevant again thanks to Ohtani. He begun that day as MLB’s home run leader (and then hit two more in a 13-8 defeat of the Detroit Tigers). On Apr. 26, Ohtani became the first player since then to start a game as a pitcher while holding the same distinction.

“When Ohtani came to the majors in this country, Babe Ruth’s daughter … told me her father would have been delighted,” Herne said. “He loved it when people went after. He felt records were there to be broken. It’s good to see somebody who can still do it.”

After Ruth, permanent two-way players became virtually non-existent on MLB rosters. There were a handful of examples in the Negro Leagues, such as Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, but even those were several generations ago.

Ohtani’s own history reinforced the difficulty of the task. In his final season in Japan in 2017, an ankle injury limited him to five appearances as a pitcher and necessitated an offseason procedure.

He played both ways during the first two-plus months of 2018 — albeit on a far less intense schedule that saw him play only 43 of the team’s first 63 games — before suffering an elbow injury that eventually required Tommy John surgery.

And after only hitting in 2019 — he also dealt with a knee issue that led to a third straight offseason with a surgery — he was shut down as pitcher in 2020 after two starts because of an arm injury and never looked right at the plate, batting a career-low .190 in the shortened season.

“I knew he was better than that at the plate. I saw him throw the baseball last year, and I knew he was better than that on the mound,” said Maddon, in his second season as Angels manager. “But I didn’t know how much better.”

It all adds to the folkloric feel of Ohtani’s current campaign, when even his bunt singles and stolen bases can whip a crowd into a frenzy.

“The easy nature of how he plays is the deceptive part,” Evans said. “Unless you’re really dialed in, or you’re an evaluator, or you’ve got a really keen eye, I think you don’t realize how good this guy can be.”

::

There are likely plenty of players with the physical tools to play both ways.

It’s something that the staff at Driveline Baseball, an advanced training center in Seattle that works with dozens of major league pitchers and hitters, has been theorizing about recently and plans to study with some of its athletes this summer.

“Rotation is rotation,” said Bill Hezel, Driveline’s director of pitching, speaking broadly of two-way skills and not Ohtani specifically. “Generally speaking, if a guy can rotate extremely well and can produce high rotational velocities and sequence their lower and upper half well, then they probably have the ability to hit a baseball very hard.”

It’s all the other skills, Hezel said, that make a two-way role such a Herculean task.

“I think the question is, how many of those guys make good swing decisions? How many of those guys consistently barrel the ball? How many of those guys can throw a breaking ball that is above the league average?” Hezel said. “I think it comes down to some of those ancillary things. It’s just got to be really hard, to think about the workload you would have to take on.”

And beyond all the stats, all the highlights, all the plaudits, those are the unseen difficulties behind Ohtani’s season — the countless little tasks that all have to be achieved in order for his skills to translate on the field.

Ohtani recognized as much this winter, taking advantage of the first fully healthy offseason of his MLB career to prepare his body and mind for a return to playing both ways.

He focused on rebuilding strength in his lower half, something he identified as a culprit in his poor offensive numbers last year. He visited Driveline, which has mastered the use of biometric analysis and scientific training methods, to work on both his pitching mechanics and his swing.

And when he arrived in Tempe, Ariz., for the start of spring training, he and his interpreter Ippei Mizuhara were pulled aside one day by Maddon and Minasian, who was meeting Ohtani for the first time as the Angels' new general manager.

Their message to him was simple, and hasn’t changed as the season’s gone along: They wanted to remove the playing time restrictions to which Ohtani had previously been subjected. Through communication, workload management and a belief in his abilities, they wanted him to master the rarest of tasks.

They wanted to see him become a full-time two-way player again.

“Revealing to him how we wanted to work this through, how to deal with him daily, and really proactively promote him to take charge of his own situation — I think there’s a confluence there that’s really influencing what you’re seeing right now,” Maddon said.

“I believe you’re going to continue to see him get better. Just got to keep him healthy, we’ve got to figure out the rest when it’s necessary. But he is so focused and motivated right now. And that’s the biggest difference I’m seeing."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports