Tragedy of Kansas City Chiefs’ Jim Tyrer shouldn’t keep him out of the Hall of Fame | Opinion

One of the saddest chapters in Kansas City Chiefs history can now be closed, thanks to newly discovered evidence about the 1980 murder-suicide of Jim and Martha Tyrer. Whether Hall of Fame voters will demonstrate the courage to acknowledge it remains to be seen.

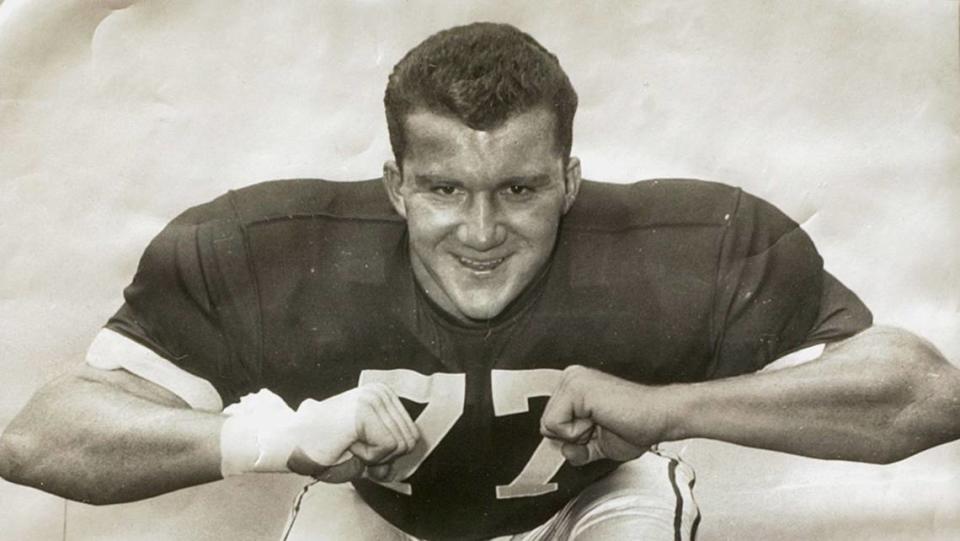

Jim Tyrer is a forgotten legend and the man responsible for protecting Hall of Fame quarterback Len Dawson. He did his job at left tackle better than anyone else between 1961 and 1975, earning nine Pro Bowl selections and six All-Pro honors. He played in Super Bowl I, was co-captain of the Super Bowl IV champion Chiefs and redefined the left tackle position for future generations. Off the field, he was a savvy businessman, humble friend and a husband who prided himself most on the four children he and wife Martha were raising: Tina, Brad, Stef and Jason. Tight end Fred Arbanas, shortly before his own death, told me that Tyrer was “The best I’ve ever seen play. He was a great athlete, a super father and a great friend.”

But outside the circle of those who knew and loved him, Tyrer is referenced in two ways: the greatest player not in the Hall of Fame and the guy who murdered his wife. In the pre-dawn hours of Sept. 15, 1980, Tyrer shot and killed Martha before killing himself. Former Kansas City Star sports writer Rick Gosselin recalls: “The city was in shock. He was the All-American story.”

In 2019, I began work on a film that detailed the tragedy, the stark contrast between the life Tyrer led and the way it ended, the kind and serene mother who was Martha Tyrer, and the admirable way her parents rallied behind their orphaned grandchildren, who responded in kind. I screened an early cut of the documentary for Tyrer’s Super Bowl IV teammates, including Arbanas, Ed Budde, Ed Lothamer, Bobby Bell and Jan Stenerud. It led to broader and deeper research for a yet-to-be-released documentary, “Beneath the Shadow,” about how the Tyrer children emerged from the tragedy and grew into the respected adults they are today.

Information I’d never guessed we’d find began to accumulate: A haunting and scattered psychological questionnaire Tyrer had partially filled out, a pastor’s recollections that Tyrer had been receiving counseling for headaches so intense “he couldn’t think straight,” and then the discovery of a doctor with firsthand information about his condition. Connecting with him was akin to throwing a Hail Mary into the distant past that connected with a stranger who knew the truth.

Douglas Paone, a former Kansas City internist now practicing in Florida, had been burdened by a memory about Jim and Martha Tyrer for more than 40 years. Martha had taken Jim to see Paone on Friday, Sept. 12, 1980, the weekend of the tragedy.

Tyrer was having headaches and abdominal pain but, more significantly, he hadn’t been himself for a while. Unable to pinpoint the problem, Paone asked the slumping and lethargic giant: “‘Jim, do you think you might have some depression?’ He said, ‘No, it’s more than that.’ But this was 1980. Brain trauma and (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) weren’t understood then.”

Paone scheduled a follow-up visit, hoping that together they could arrive at an answer. “As we were leaving my office and walking down the hall, Martha grabbed my arm and looked at me: ‘There’s something wrong with him.’ It kinda scared me. She wanted me to know there was something wrong with him. It got my attention.” He arranged for them to see a psychiatrist on Monday morning. They agreed. It was all he could think to do. “That was the last time I ever saw them.”

First-ballot finalist at time of murder-suicide

After my phone conversation with Paone, we arranged to meet at his office in Florida. In the interim, he dug into his patient’s case and the literature on brain trauma and CTE. When we met, he got straight to the point.

“He had CTE. No doubt in my mind. You couldn’t even pick a person that had a better presentation of the disease. As an internist, I have to make diagnoses without slides, without scans. If it walks like a duck, quacks, water runs off its back and its name is Daffy. It’s not a zebra. He had CTE.” Paone presented me with a written diagnosis. Like most neurodegenerative diseases, such as such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, CTE can’t be definitively diagnosed except in an autopsy.

Tyrer was a first-ballot finalist for the Hall of Fame at the time of the murder-suicide. Although the rules of the Hall of Fame are completely confined to the football field, his name never again appeared on the ballot. As Chris Nowinski, CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation explained to Tyrer’s eldest son, Brad: “I cannot imagine that they would want to even entertain the thought that you could forgive somebody for that act because it was actually football that changed his brain, changed his behavior and played a role in what happened.” It’s easier to avoid than it is to forgive.

Which leads to another thing never shared with the public: where Tyrer is buried. Recall that it was Martha’s parents who stepped in and raised the Tyrer children after the tragedy. They’d known Jim since he was a teenager. As Martha’s sister Jan Lundstrom says: “Mom and Dad were able to forgive Jim for this. Martha loved Jim, the kids loved Jim. Period. Mom and Dad loved Jim. And you can’t take all that love and turn it to hate.” So, when Martha’s father, Truman Cline, died in 1988, his wife Lucille suggested that the ashes of Jim and Martha be put in the coffin with Truman. Tina Tyrer tucked the box containing the ashes under her coat and went into the funeral home. “I opened the casket and put the box in there with a thank you note to Grandpa. I know that’s illegal. But, hey,” she said, shrugging with a chuckle. Grandma Lucille Cline would die in 2002 and be buried alongside.

What kind of person allows for the ashes of the man who murdered their child to be buried with them? Only someone who truly knew that man and forgave him.

Ignoring Jim Tyrer has been a convenient way for the NFL to sidestep its messy legacy. But in so doing, it dishonors players and their families who’ve made enormous sacrifices on and off the field. We have a diagnosis. We have context. We have forgiveness. What we don’t have is a public acknowledgment of Jim Tyrer’s rightful place in the Hall of Fame by the sport he unwittingly gave his and his wife’s life to.

Kevin Patrick Allen is a Kansas City-based documentary filmmaker. He directed the upcoming “Beneath the Shadow” about Jim Tyrer’s family.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports