Title IX aimed to get women into grad schools. Over 50 years, it shaped their role in sports.

Clarification: This story has been updated with additional context about the Cohen v. Brown University settlement agreement.

This project is a collaboration between USA TODAY and The 19th.

This June marks the 50th anniversary of the passage of Title IX, the landmark law that banned sex-based discrimination in schools. Initially introduced in hopes of getting more women into graduate schools, the law today is most commonly associated instead with athletics because of its seismic impact on women's sports. When the law passed, fewer than 300,000 girls played high school sports and 32,000 played in college. The exponential increase in girls’ and women’s participation over the past five decades, and the explosion in popularity of women’s college and professional sports, can be directly linked to the law.

But did you know Title IX offers a host of other protections, too? Since its passage, the law has been cited in court cases to defend students from sexual harassment and assault, ensure the rights of transgender students and protect pregnant students from discrimination. Though the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination in federally funded programs – including education – on the basis of race, color and national origin, sex was not included, which opened the door for Title IX’s passage just two years after Congress held its first hearings on sex discrimination in higher education.

Despite this, most people still don’t fully understand how the legislation works, or what it all entails. According to a poll conducted by Ipsos in April, nearly 75% of students and 60% of parents say they know “nothing at all” about Title IX. Still, most agree it’s been a force for good: According to a Pew poll, 63% of Americans agree the monumental civil rights law has had “a positive impact” on gender equality in the U.S.

Five decades after its passage, Title IX has changed the landscape of higher education. This timeline illustrates the law's impact on the field and in classrooms.

About the series

USA TODAY’s “Title IX: Falling short at 50” exposes how top U.S. colleges and universities still fail to live up to the landmark law that bans sexual discrimination in education. Title IX, which turned 50 this summer, requires equity across a broad range of areas in academics and athletics. Despite tremendous gains during the past five decades, many colleges and universities fall short, leaving women struggling for equal footing.

1972

Title IX passes as part of the Education Amendments of 1972, requiring schools that receive federal funds to guarantee gender equity across campus.

President Richard Nixon signs it into law amid little fanfare, but U.S. Rep. Patsy Mink, D-Hawaii, understands the long-reaching implications, later explaining her motivation in sponsoring the bill: “So long as any part of our society adheres to a sexist notion that men should do certain things and women should do certain things and then begin to inculcate our babies with these certain notions through curriculum development and so forth, then we’ll never be rid of the basic causes of sex discrimination.

“I suppose the purpose of my bill is really to free the human spirit to make it possible for everyone to achieve according to their talents and wishes,” Mink said.

1973

In a wave of renewed interest in women’s sports after the passage of Title IX, tennis superstar Billie Jean King beats self-described “male chauvinist” Bobby Riggs 6-4, 6-3, 6-3 in the “Battle of the Sexes,” a match watched by 90 million people worldwide. It is one of several seminal moments for women’s sports over the next five decades.

“I thought it would set us back 50 years if I didn’t win that match,” King says afterward. That same year King – who won 39 major titles, including 12 in singles, in her career – founds the Women’s Tennis Association to protest the inequity in prize money awarded in men’s vs. women’s matches.

1974

U.S. Sen. Birch Bayh, D-Ind., who sponsored the legislation in the Senate, insists on including sports in Title IX enforcement after pushback from colleges, coaches and conferences opposed to paying for women’s sports teams, too.

Motivated by protecting football, U.S. Rep. John Tower, R-Texas, introduces the Tower Amendment to exempt revenue-producing sports from Title IX requirements. It fails, and the Javits Amendment is adopted instead. Introduced by U.S. Sen. Jacob Javits, R-N.Y., it allows for “reasonable provisions considering the nature of particular sports” – meaning that spending on teams doesn’t have to be equal if there are different needs.

In Knoxville, the University of Tennessee hires Pat Summitt as its women’s basketball coach. Summitt would go on to win eight national championships, becoming one of the most iconic figures in sports. At the beginning of Title IX, 90% of all women’s teams were coached by women. Today, that number is 43%.

Also that year, Ann Meyers becomes the first woman to receive a four-year athletic scholarship, opening the door for thousands of young women to follow her. Though colleges were given three years to comply with the law, many schools took steps to start adding teams before that deadline. Meyers would go on to become a four-year All-American at UCLA and the first – and still only – woman to sign an NBA contract.

“I always knew I was capable of pursuing sports because I saw women doing it,” Meyers says now. “The young athletes today, they don’t know what Title IX is, they don’t understand it … I think that it needs to be taught — at the (Amateur Athletic Union) level, at the high school level and the college level. They need to continue to fight for this law.”

1975

The Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) – which would later be replaced by the Department of Education – passes final Title IX regulations, giving colleges three years to comply with the new rules.

1976

The NCAA sues to challenge the legality of Title IX, but the case is dismissed two years later.

At Yale, female rowers complain about their lack of access to post-practice showers at the boathouse. The men’s team readily had access, while the women had to ride, cold and wet, on a bus back to campus. The women protest in an administration office, writing “Title IX” on their naked torsos while reading a statement that says, “These are the bodies Yale is exploiting.”

1979

For the first time in the history of American higher education, female enrollment (50.9%) surpasses male enrollment. That trend continues today.

HEW establishes the three-prong test to gauge compliance with Title IX for colleges and universities. That test is still used today, as schools pick one of three ways to prove Title IX compliance with regards to athletic participation opportunities: proportionality, where gender breakdowns of schools’ roster spots reflect their enrollment; or showing a history and continuing practice of increasing opportunities for the underrepresented sex, usually women; or demonstrating that the athletic interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex are being met.

1980

The newly created Department of Education takes over federal education responsibilities, granting primary Title IX oversight to the Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

Elsewhere, five Yale students file a lawsuit arguing Title IX requires schools to have a grievance procedure in place to address sexual harassment. Though the students did not win in Alexander v. Yale, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals acknowledges that sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination prohibited by Title IX.

1982

The Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women folds after a protracted fight in which the NCAA uses its strength with men’s championships to force schools to choose between them.

1984

In Grove City v. Bell, the Supreme Court rules that Title IX applies only to programs receiving targeted federal funds – effectively ending enforcement of the law, but especially related to athletics. Grove City is a private, faith-based school in Pennsylvania that had long declined to take any direct forms of federal assistance. But when the government pointed out that 140 students received federal grants, it required the school to prove it was following Title IX and not discriminating based on sex. Ultimately, the court rules 6-3 that Title IX requirements do not apply across an entire institution but only to the particular program receiving federal dollars.

1988

Despite President Ronald Reagan’s veto, Congress passes the Civil Rights Restoration Act, restoring the protections nullified in Grove City v. Bell.

Also, in the first case tried against an athletic department for discrimination against female athletes, a judge rules in favor of the women in Haffer v. Temple University, resulting in new and stronger directions for athletic departments related to their budgets, scholarships and participation rates of male and female athletes.

“The Temple University trial and settlement showed schools around the country that they could and would be held accountable for violating Title IX,” said Arthur Bryant, one of the attorneys who represented the athletes and continues to litigate Title IX cases.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

1992

In Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools, a high school student sues after notifying the school of harassment by her teacher. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision allows for monetary damages under Title IX, opening a new way to help enforce the law. Previously, schools were punished only with probation.

Meanwhile, the NCAA commissions a Gender Equity Report, and a survey of its membership reveals that while undergraduate enrollment is roughly equal between men and women, men make up 70% of athletic participants and receive 70% of athletic scholarships, 77% of operating budgets and 83% of recruiting money. Additionally, it shows that fewer than 50% of women’s teams have female head coaches, as do just 1% of men’s teams.

1994

The Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act passes, requiring schools to report information about their athletic programs – such as sports sponsored, coaches and funding – to the federal government.

“Existing structures are hard to change,” former U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley Braun, D-Ill., who sponsored the law, says now. “When you get pushback and people are saying, ‘We’ve always done it this way’ or ‘Don’t fool with my fill-in-the-blank team,’ when you get that – particularly when people are not going to tell you the truth – what you want to do is set up a set of transparencies so people can see exactly what’s going on.”

1996

In Cohen v. Brown University, plaintiff Amy Cohen challenges the elimination of women’s gymnastics and volleyball teams. The school argues women are less interested in sports than men. Brown loses and is required to restore the programs. It remains under monitoring today. The plaintiffs argued Brown violated the Title IX settlement agreement in 2020 when it eliminated 11 sports – six men's and five women's – but then added back three men's sports, thus widening the gender gap beyond what the agreement allowed. The parties reached a new settlement that ends in 2024.

1997

OCR issues its first guidance establishing the responsibility of schools to prevent and address sexual harassment under Title IX.

Also that year, after massive growth at the collegiate level since the passage of Title IX, the WNBA tips off for its first season.

“The experience that I’ve had as a professional athlete has been the greatest thing that’s ever happened to me in my life,” says Nancy Lieberman, who at 39 was the oldest player in the WNBA’s inaugural season. “I am who I am because of opportunity.”

1998

In Chipman v. Grant County School District, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky grants pregnant students’ preliminary injunction after they were removed from the honors society shortly after becoming pregnant out of wedlock, arguing that male students who had premarital sex were not equally punished.

1999

In May, during Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, the Supreme Court establishes the “deliberately indifferent” standard for schools to be held liable for sexual harassment.

In July, the U.S. Women’s National Team wins the World Cup in front of 90,185 spectators at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California, setting an attendance record for women’s sporting events that would stand for more than 20 years. After scoring the winning penalty kick, Brandi Chastain celebrates by ripping off her jersey and falling to her knees, which becomes one of the most iconic sports images in history. The team was a direct result of Title IX, as the legislation opened the door for millions of young women to participate in sports.

“Obviously that was a ground-shaking moment,” Chastain later told ABC News. “To see a women’s event on that stage, with that capacity, with that attention, had never happened anywhere. It just captured the imagination, the hearts and the minds to say, ‘women’s sports matters.’”

2001

OCR issues further guidance clarifying schools’ obligation to address sexual harassment under Title IX.

2005

In Jackson v. Birmingham Board of Education, the Supreme Court rules that individuals, including coaches and teachers, have a “right of action” under Title IX if they’re retaliated against for protesting sex discrimination.

2011

The Obama administration’s guidance regarding sexual harassment prompts a sea change in university staffing, student activism and OCR complaints of schools failing to properly investigate or adjudicate sexual harassment.

2012

American women dominate at the London Olympics, winning 58 medals compared to 45 for the men, the first time U.S. women won more medals than their male counterparts. Had the American women been their own country, they would have finished fourth in the medal count. At every Olympics since, save for the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, American women have won more medals than American men.

2013

Building off the nearly two-decade success of the dominant U.S. Women’s National Team, and in a nod to the NCAA essentially being a feeder program, the National Women’s Soccer League kicks off. It is the third women’s professional soccer league in America since 2001; the other two previously folded.

In June, for the first time, OCR issues guidance clarifying the rights of pregnant and parenting students.

2016

The Department of Justice and Department of Education issue guidance on protecting transgender students, saying that Title IX bans discrimination based on a student’s gender identity.

2017

The Trump administration revokes the 2011 and 2016 guidance on sexual harassment and transgender students, among others. Led by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and complaints from men’s rights activists, the administration embarks on a rulemaking process that limits the scope of sexual assault complaints schools are responsible for and bolsters due-process rights of responding parties – moves that advocates argue are meant to deter survivors from coming forward.

“This will make schools less safe,” Jess Davidson, the executive director of End Rape on Campus, told Vox. “The goal here is to keep people from reporting.”

2019

High school participation numbers show that girls’ sports still have not reached the total of boys’ sports in 1972, when Title IX was first passed.

2021

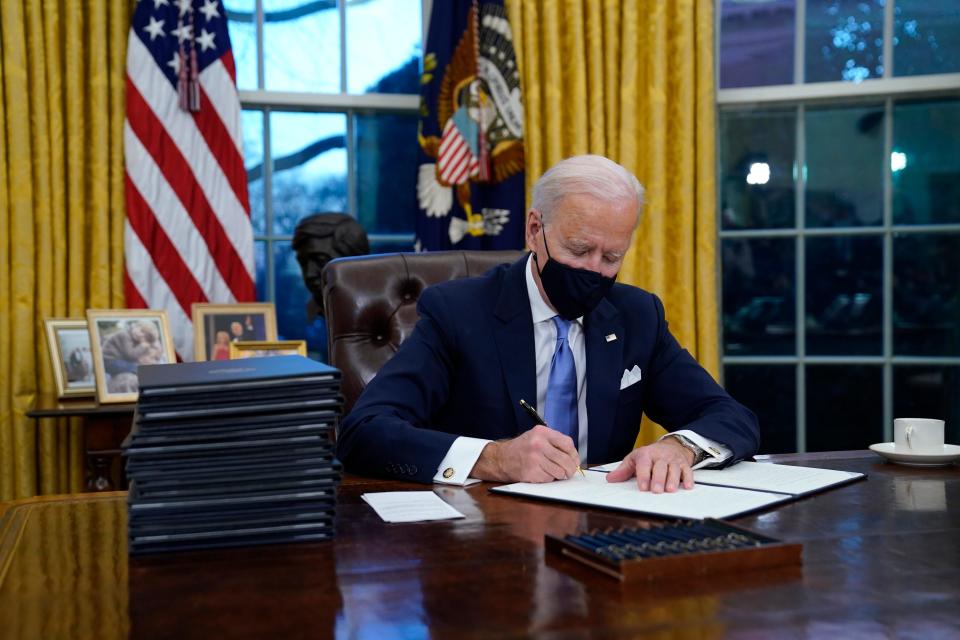

In executive orders spaced just six weeks apart, President Joe Biden cites Title IX to take steps to protect LGBTQ students. Executive Order 13988, signed on Jan. 20, states, “All persons should receive equal treatment under the law, no matter their gender identity or sexual orientation.”

In response to outcry over the disparate weight room facilities provided to players during the 2021 NCAA men’s and women’s basketball tournaments, the NCAA commissions an independent investigation and shares the findings. The first report, released in August, concludes that the NCAA “prioritizes men’s basketball, contributing to gender inequity” and specifically that the organization is “significantly undervaluing women’s basketball.” The second report, released in October, comes to the overall conclusion that the NCAA has neglected women’s sports.

“Title IX is an ongoing, living, breathing organism that you have to pay attention to every year,” says Texas executive senior associate athletic director Chris Plonsky.

2022

In May, the U.S. Soccer Federation agrees to pay U.S. Women’s National Team players $24 million to settle a class-action equal pay lawsuit filed three years earlier, and it commits to paying its men’s and women’s national teams the same going forward. The settlement is contingent upon a new collective bargaining agreement and, three months later, U.S. Soccer announces a first-of-its-kind agreement that will see both the men’s and women’s teams paid equally – including an equal split of World Cup prize money.

“What we’ve done is a landmark in progress (toward) gender equity,” says USWNT forward Midge Purce. “We set a new standard of value for women in the workforce.”

On June 23, Title IX turns 50. In the past five decades, participation in girls’ and women’s sports has exploded, with 3.4 million high school girls playing sports and 219,000 women playing in the NCAA. But reporting shows female athletes are still being significantly shortchanged by their schools.

“I think we’ve just gotten used to kind of playing with less,” says Oregon basketball player Sedona Prince, who has become a vocal advocate for equity in women’s sports. “It’s sad, because we’ve gotten used to being screwed over.”

Explore the series

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How Title IX changed college sports for women over the past 50 years

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports