The comic that sparked Japan's interest in the NBA

Growing up in Hong Kong, one of my favorite hobbies next to begging my parents to buy me every single toy car was reading manga. I devoured every single Japanese comic I could get my hands on.

As a kid, it would be a blessing when my mom would actually buy a comic for me. They usually came in volumes (think: the equivalent of graphic novels collecting single issue comics in America). I would read it right away, finish it too fast, go back and read it again, and revisit it before the next volume came out.

Most of my manga reading came from visiting my cousin’s apartment. He was older, and could afford to purchase the volumes for himself. On his shelf was the most prestigious manga collection I had ever seen.

He was usually at work or out when I visited, which allowed me to bury myself in his collection and read for hours. It was one of those lazy afternoons when I pulled a manga series I had never heard of from the shelf.

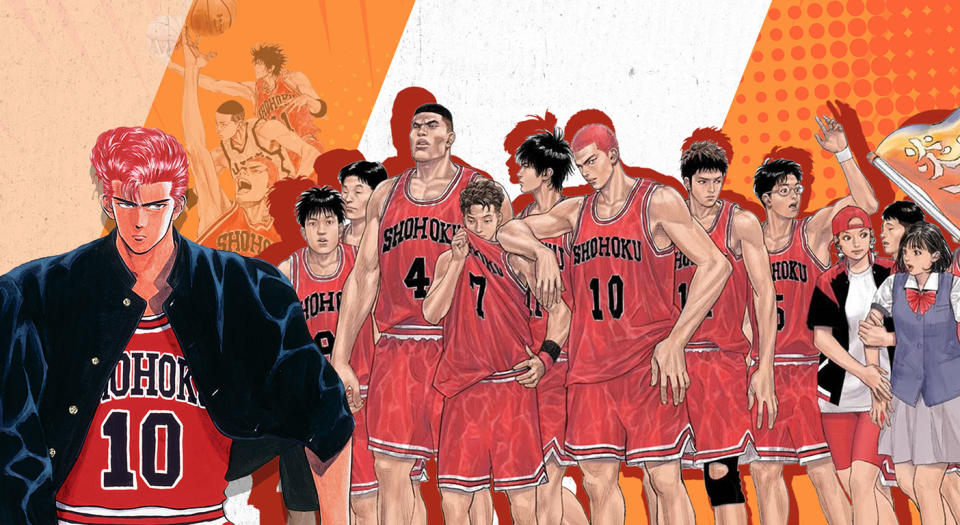

It was called Slam Dunk.

Based on the cover of the manga, I expected a basketball story. Instead, the early chapters featured the beginning of a high school love story. Hanamachi Sakuragi, a high school slacker and the main protagonist of the story, is willing to do anything to impress Haruko Akagi, the girl he is in love with. So, even without any knowledge of the sport, he joins the school’s basketball team.

Through Sakuragi’s lens, the manga explores his journey from basketball novice to someone who eventually falls in love with the sport. Through 276 chapters collected over 31 volumes, Slam Dunk introduced some of the most iconic characters and storylines I’ve ever read in manga form.

The story was impossible to put down. Over the next few years, I managed to track down and read all of the volumes. When I finished Slam Dunk in its entirety for the first time, I went back and read it again. Every few years, I still revisit bits and parts of the story.

Slam Dunk was my first introduction to basketball.

It also inspired an entire generation of basketball players in Japan.

***

This week, the Toronto Raptors and Houston Rockets will be playing two exhibition games in Japan. Basketball still isn’t a top-tier sport in terms of popularity in Japan, but it is growing, and it’s not an exaggeration to credit Slam Dunk for influencing an entire country’s interest in it.

Written and illustrated by Takehiko Inoue, Slam Dunk ran as a weekly serialized manga series from 1990 to 1996. It came at a time when the NBA’s popularity was reaching new heights, thanks to the USA Dream Team’s performance at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, and the dominance of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. Basketball started becoming relevant in mainstream pop culture, and became a global sport.

Inoue was one of the people overseas who was paying attention. He played basketball in high school and was inspired to write and draw Slam Dunk to share his enjoyment of the sport with a wider audience.

Inoue drew clear influences from the NBA at the time. Sakuragi’s delinquent behavior and obsession with becoming “The Rebound King” appears to be inspired by Dennis Rodman. Sakuragi’s teammate and captain of the Shohoku basketball team, Takenori Akagi, is a physical center reminiscent of Patrick Ewing. Kaede Rukawa, the best player on the team, is the character closest to Michael Jordan.

The manga was a resounding success in Japan, selling over 120 million copies. It was also adapted into an anime television series. A pop culture phenomenon, Slam Dunk action figures, posters and other manga-related merchandise were sold everywhere. In 2014, Nike released a pair of Air Jordan 6 “Slam Dunk” featuring Shohoku colors and imagery of Sakuragi on the sneakers.

The manga has been licensed in 17 countries, including by Viz Media, an American manga publisher who started releasing Slam Dunk in English in 2008. David Brothers is a Viz Media editor. He discovered Slam Dunk a decade ago.

“It works as a drama, a sports comic and a way to gradually introduce people to basketball,” Brothers says. “The characters have weight, they have energy, and thanks to his dramatic writing, they have genuine, resonant motivations too. The book’s not just focused on winning. It’s focused on getting better at your craft and becoming a better person by learning to work as part of a team rather than a lone wolf.”

One of the best qualities about Slam Dunk is how it avoids to tell a cliché sports story. The Shohoku team doesn’t always win. Sakuragi’s path from basketball novice to irreplaceable player on the team isn’t without failures along the way. The ending of the story is left open-ended.

Slam Dunk’s other appeal comes from Inoue’s illustrations. Some of the basketball scenes in the manga are inspired by Inoue’s favorite NBA moments.

Andy Nakatani has worked at Viz Media for two decades and discovered Slam Dunk when he was living in Japan in the 1990s. “The manga makes it feel like you’re right there on the court in the middle of all the action,” Nakatani says. “The story pulls you in with amazing character development, perfect comedic timing and dramatically moving moments that give you goosebumps.”

In 2012, the manga was voted the second most popular manga of all-time in a survey.

***

The legacy of Slam Dunk won’t be its popularity in Japan, but the fact it actually inspired basketball players who are now in the NBA.

In June, Rui Hachimura became the first Japanese-born player ever taken in the first round of the NBA when the Washington Wizards selected him ninth overall.

There are currently three Japanese players in the NBA. Hachimura is joined by Yuta Watanabe, who went undrafted last year after a four-year career at George Washington University and appeared in 15 regular season games with the Memphis Grizzlies, and Yudai Baba, who signed with the Dallas Mavericks in September and is part of their training camp roster.

Hachimura, born two years after Slam Dunk ended in 1996, has credited the manga series for influencing his interest in basketball growing up. Watanabe has a similar story. Although he was born in 1994, at the height of Slam Dunk’s popularity, the 24-year-old discovered the manga through his father.

“I got into it and couldn’t stop reading it,” Watanabe says. “I finished it in like three days.”

In the years since he first discovered the series, Watanabe estimates he has re-read Slam Dunk over 100 times.

“I’m not even kidding,” he says. “I’ve read it over and over and over again.”

Watanabe most recently read the series in April, when he went home to Japan after Memphis’s season ended.

An avid manga reader growing up, Watanabe says Slam Dunk is his clear-cut favorite. He runs through a long list of characters when asked to choose a favorite, before settling on Akira Sendoh, one of the most talented and easy-going, care-free characters in the series.

While NBA players in North America often talk about pretending to be Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, or Michael Jordan growing up, for a generation of Japanese players, their inspirations came from fictional characters like Sakuragi, Rukawa and Sendoh.

In 2012, the Japanese Basketball Association recognized Slam Dunk’s influence by awarding Inoue with a special commendation for his contribution to the popularity of the sport of basketball in Japan, in addition to recognizing a scholarship program Inoue established in 2007 which helped send Japan’s best basketball players to study abroad in the United States.

Without the popular manga, it is arguable whether players like Hachimura and Watanabe would have pursued a professional basketball career. Today, Watanabe still can’t believe he went from drawing inspiration from a manga to playing in the NBA.

“I was just a kid when I started reading Slam Dunk,” Watanabe says. “Now I’m a guy who made it in the United States and is playing in the NBA.”

***

Despite the craze over the manga series in Japan, Slam Dunk has never crossed into the mainstream in North America. Michael Montesa, an editor at Viz Media, admits sales numbers for the manga series was disappointing.

“The Venn diagram intersection of sports fans who are manga fans and manga fans who are sports fans is very small,” Montesa says. “Sports manga have always struggled in the U.S. market unless there was some other factor that appealed to general manga fans. Or maybe the way to say it is, manga fans don't read sports manga because they're intrinsically interested in whatever sport it is that's being featured, they're into it for certain specific aspects of the characters.”

Brothers views Slam Dunk as a series that could appeal to anyone looking for an entertaining drama about a high school basketball team.

“Something more Friday Night Lights than Bad News Bears, but with similar elements of both,” Brothers says. “If you want to read a series where characters actually grow and change, and victory isn't assured, Slam Dunk is a wild ride. It's like watching basketball, one of my most favorite sports, from an all-new angle.”

In the end, the cultural differences when it comes to appreciating comics and anime might prevent Slam Dunk from becoming popular in North America.

“Our respective comics industries are so different,” Brothers says. “We don’t really have a sports comics tradition here. The superheroes dominate the conversation [here].”

To Brothers’ point, even as NBA players have gravitated towards manga and anime, most of them lean towards more superhero-centric series like Dragon Ball Z and Naruto.

Watanabe says he hasn’t talked to any of his NBA teammates about Slam Dunk. While he sounds unsure about whether they would actually give it a chance, Watanabe has no doubt if they did, they will appreciate it just as much.

“If they start reading,” Watanabe says. “I think they’ll really enjoy it.”

Watch more from Yahoo Sports Canada on YouTube

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports