Russia’s cyber gangs are attacking the soft underbelly of the UK economy

Previously the scariest thing that could be said about Klopp was his teeth – that was until the manager of Liverpool football club paid for cosmetic dentistry to transform his crooked gnashers into a set of dazzling white pearlers.

Now, there’s a new and far scarier version: Clop – a Russian cybercrime outfit behind a massive hack that has exposed the personal details of tens of thousands of employees at the BBC, British Airways and Boots.

The proliferation of cyber attacks against major UK companies and institutions is one of the biggest threats that this country faces today.

The assaults are becoming more frequent, more damaging, and more sophisticated as cyber-criminals hone their skills, in a constant attempt to stay one step ahead of the systems designed to repel their raids.

No organisation is safe, and there is nothing it seems, that the gangs aren’t able to obtain.

BA, which has 34,000 employees in the UK, has told staff that hackers may have stolen their bank account details, national insurance numbers, home addresses and dates of birth, which pretty much covers the entire gamut of private information that you could collect about any individual.

This is the soft underbelly of the British economy.

The rise of the internet and the smartphone mean every detail of our personal lives now exist in hundreds of different databases, which in turn are in the hands of every major corporation that touches our lives, and yet too many of these companies are unable to guarantee that they can be trusted to keep our data safe.

Every one of us is complicit in this deeply uncertain arrangement. Whether it’s our bank, utility supplier, holiday provider or increasingly any major retailer, we unquestioningly hand over highly sensitive information all the time that any cyber criminal would regard as a treasure trove.

I did it twice today on the train into London with two separate online purchases on my iPhone, signing up to companies that I have never used before – without batting an eyelid.

We set up new customer accounts, create new usernames and too often use the same password for everything, again with little thought as to the possible consequences. But too often our data ends up in the wrong hands with dire consequences.

Part of the problem is that the hackers are becoming more sophisticated, and harder to identify as a result of the blurring of the lines between criminal enterprises and state-sponsored activity.

Clop is part of a growing web of Russian hacker gangs who are targeting the West, and whose malevolent activities are increasingly being sanctioned by the Kremlin.

It is, in effect, an unofficial or private army, not unlike the Wagner Group of mercenaries that have been doing much of Moscow’s dirty work on the frontline in Ukraine.

Wagner founder Yevgeniy Prigozhin is also suspected of links to what the UK Government called Russia’s “most infamous and wide-ranging bot-farm”, the Internet Research Agency.

The St Petersburg-based group is accused of being at the forefront of the Kremlin’s large-scale disinformation campaign to manipulate international public opinion on Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine.

It is the merging of genuine conflict with economic warfare, and the West’s sanctions against Russia, while necessary, have dragged companies onto a more dangerous international frontline.

But companies can, and must do more to prevent such attacks.

A recent major hack at Capita prompted it to promise to invest millions more in reinforcing its cyber security defences, which is the same as saying that it hadn’t spent enough on IT security previously.

That may explain why it took the company ten days to discover the breach.

Many are paying the price for outsourcing technology in an effort to cut costs but how can any chief executive be certain that someone else’s IT is properly safeguarded when most can’t be sure that their own firewalls are sound.

Zellis, the payroll provider at the heart of the data breach that the BBC and others have suffered, claims to handle contracts for 42pc of the FTSE 100 with a total value of £28bn.

The breach stems from a widely used piece of software called Moveit, which is used by thousands of companies around the world.

No wonder that cyber experts are warning that the incident could be the tip of the iceberg.

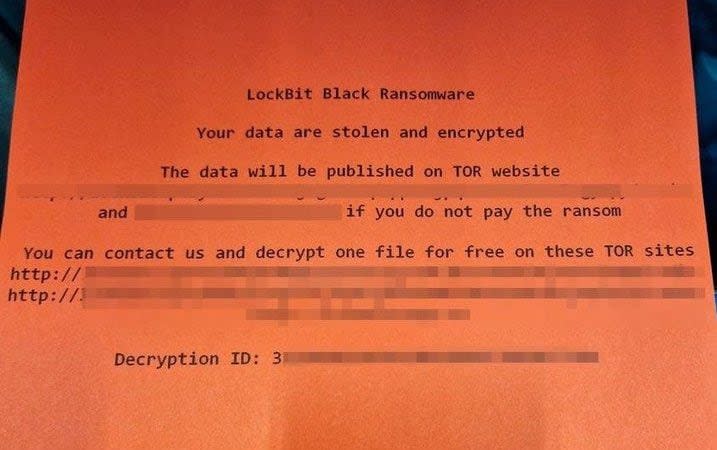

The costs alone of failing to batten down the hatches should force a wake-up call. It took the publisher of the Guardian newspaper three months to get back on its feet after it was hit by a ransomware attack last December.

Imagine if that was the NHS or the national grid.

When it comes to corporate cyber security there is more than a whiff of complacency, mixed with ignorance and naivety at the top.

The issue has gone from being something that someone else should worry about to something the board should worry about but it hasn’t happened fast enough.

In the past, too many firms have paid little more than lip service to cyber attacks, setting aside a few hundred words in the annual report to talk about how seriously they are taking the threat, without actually taking it seriously.

But warm words are not going to keep a business safe from today’s cyber terrorists.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports