I Represent Migrant Children in Immigration Court. This Is What It's Like.

The immigration judge cleared her throat and called *Layla’s name. An 8-year-old girl jumped up from her seat in the back of the courtroom and skipped up to the front. Layla was wearing shiny white shoes and a fluffy pink dress. Her long, black hair was neatly brushed into two bouncing braids. She took a seat at an empty table at the front of the courtroom. Across the aisle sat an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) attorney in a suit. He stared into his computer screen where he read information about Layla—my future client—as they began her deportation proceedings.

Layla was born in El Salvador, but fled to the United States after suffering sexual, physical, and psychological abuse in her home country. When Layla was 6 years old, her mother moved to New York in search of a higher income after years of struggling as a single mother. She left her only daughter in the care of family members in hopes of giving her a better life with the money she sent from abroad. To her horror, Layla’s mother later discovered that the girl was repeatedly raped, beaten with a broom, and forced to sleep on a towel on the floor of a closet while living with family. One day, Layla’s teacher contacted her mother in the United States and told her that her daughter showed signs of severe neglect. Layla’s mother was terrified for her daughter’s life, and knew that the treacherous journey to the United States was safer than having Layla remain with her abusive relatives.

Two weeks later, Layla left El Salvador with nothing but the clothes on her back in search of safety, stability, and a better future.

The child made the dangerous journey from Central America to the United States by car, bus, train, and on foot with a group of strangers. When she walked over the border into Texas, Layla flung herself into the arms of a border patrol officer, thinking she was finally safe, she told me later. Her mother is here in the U.S., and that’s enough for this place to be a beacon of safety. And although this is what most of our clients experience, it is actually a false sense of security considering the hurdles they face once in this country.

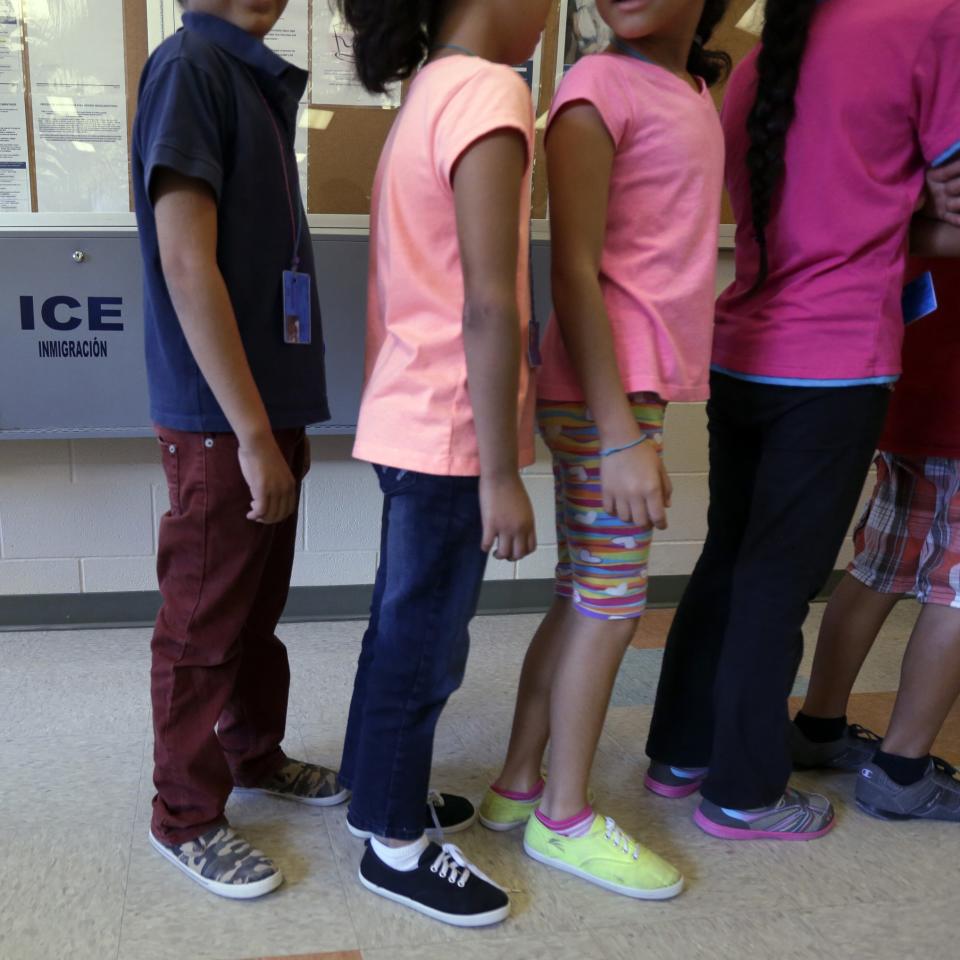

Because she did not have a valid visa, however, she was immediately placed in deportation proceedings. Layla was released to live with her mother in Brooklyn, pending her imminent deportation in New York immigration court. Because the U.S. government does not provide free attorneys to refugee children like Layla, they are forced to appear in immigration court alone.

On the day that I met Layla, she was wearing that pink fluffy dress and sitting at the front of the courtroom by herself. She tried to answer the judge’s questions and understand ICE’s explanation for why she is “removable as charged,” which is a difficult task for a trained immigration attorney like myself, not to mention an 8-year-old child.

I stood in the back of the courtroom and observed the hearing. While part of me was stunned by the sight of a little girl alone in court, I had also grown accustomed to this familiar scene. I am an attorney at the Safe Passage Project, a non-profit in New York City that provides free legal representation to immigrant children facing deportation. We are housed at New York Law School and, since our inception, have been located just a few blocks from the immigration court in New York. Our team of 20 people is currently providing free legal representation to over 700 children just like Layla.

Luckily, the judge granted a continuance that day in court to give Layla an opportunity to try to find an attorney. After the proceeding, Layla ran to her mother in the back of the courtroom. I approached them in the hallway and offered them a free legal screening to determine if Safe Passage could provide Layla with free legal representation. We walked down the hall and squeezed into the corner of an unoccupied courtroom where I asked Layla and her mother questions, taking notes on a worn yellow legal pad. I had only known them for five minutes, but I needed them to disclose personal and painful details about their lives in Central America in order to determine whether Safe Passage could take on Layla’s case.

KM_364e-20180726113221

The following week, I officially became Layla’s attorney and began the process of helping her apply for asylum. Asylum is a protection for people who are afraid to return to their home country because they have faced serious harm in the past or will face serious harm in the future. In order for me to successfully represent Layla, I had to meet with her regularly to build trust and learn more details of her abuse. I worked closely with the Safe Passage social work team, who enrolled Layla in therapy and helped me navigate the difficult task of talking to a child about such sensitive matters.

Each time we met to develop her case, Layla would get a running start and greet me with an enormous hug. She brought so much energy and happiness to the office. I would set up the meeting area with paper and markers; Layla is a talented artist and it helped her tell her story. She would draw through the pain and elaborate on the details of her abuse. We would take frequent breaks and play games and little by little we were able to build her case.

Layla’s asylum hearing was one of the most difficult yet rewarding days of my life. I met Layla and her mother that morning to embark on the long train ride to the asylum office. Loretta Lopez, the bilingual case manager at Safe Passage who was going to be interpreting for the hearing, joined us as well. When we finally arrived at the building, Layla’s mother gave her a kiss and then left us to wait at another location. She is undocumented herself and was too afraid to enter this U.S. government building. Layla, Loretta and I headed inside the building without her.

When she was asked to go into more details about the incidents of the rape, Layla turned to me, looked up, and whispered, “do I have to?”

We waited for four hours before Layla’s case was called. In the meantime we drew pictures, told each other fantastical stories, and listened to Layla’s made-up songs. We kept giggling in a silent room full of nervous people who were also waiting for their case to be heard. Many of them looked in our direction and smiled at us. The asylum officer finally called Layla’s case and led us to the room for her hearing. Then Layla was instructed to stand up, raise her right hand, and swear under oath that she would tell the truth.

For the next three hours, Layla testified about the sexual, physical, and psychological abuse she suffered in El Salvador. When she was asked to go into more details about the incidents of the rape, Layla turned to me, looked up, and whispered, “do I have to?” I swallowed the lump in my throat and gently nodded yes.

After Layla’s testimony was complete, I stood up and delivered my closing argument. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see Layla staring at me. I finished my closing and suddenly Layla leapt into my arms. I caught her embrace and looked over at the asylum officer. He was smiling. I then looked at my coworker, Loretta, and she was holding back tears. Layla’s hug had transported all of us outside of the formalities and legalities of the immigration process.

KM_364e-20180726113221

Three weeks later, we received the news that Layla was granted asylum. I immediately called her mother and we cried tears of joy on the phone together. Then I told Layla, expecting to hear excitement in her voice. Instead, she asked “But what about my mom?”

There is a harsh reality in a seemingly happy ending. Layla now has legal status as an asylee, but her mother remains undocumented. There is no legal way for Layla to immediately transfer her own status to her mother. When Layla turns 18, she can become a U.S. citizen through naturalization. It won’t be until Layla turns 21 that she will be able to apply for her mother to receive legal immigration status. But 10 years is an eternity for her mother to have to live in the shadows and hope that she is not detected by immigration authorities. This is an obstacle that many of our clients face. If the caretaker is deported, then the family is faced with the impossible decision of separating the family or having the child return with them to the country that they were fleeing from. Layla’s case demonstrates how the immigration laws in this country could tear apart families, and impact children who have a legal right to be here.

Safe Passage fights for children like Layla every day. In addition to representing children who have traveled here alone, we are also representing over 30 children who were recently separated from their parents at the southern border. We believe that no child should have to face the immigration process alone and that families should not be separated.

This particular case is one that will stay with me forever. I have kept a folder with the countless drawings that Layla has made for me. My favorite one is of me, Layla, and Loretta wearing capes and standing in the Wonder Woman pose. It is children like Layla that make it possible for advocates to keep fighting the fight. She has been through unimaginable pain in her life, but she still exudes light, happiness, and hope. She hugs limitlessly, laughs without restraint, and can see the endless possibilities for her future.

She is a reminder to me that every day, we have a choice.

*Name has been changed to protect privacy

Lauren Blodgett is an immigration attorney at a non-profit in New York, where she provides free legal representation to refugee children.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports