Remembering the day Jackie Robinson played in Raleigh, breaking the city’s race barrier

In 1950, Raleigh’s humble baseball park with its rickety bleachers and patchy infield grass hosted the base-stealing, hit-smashing star of the Brooklyn Dodgers, a towering civil rights hero who was very likely the first Black player on its scruffy diamond.

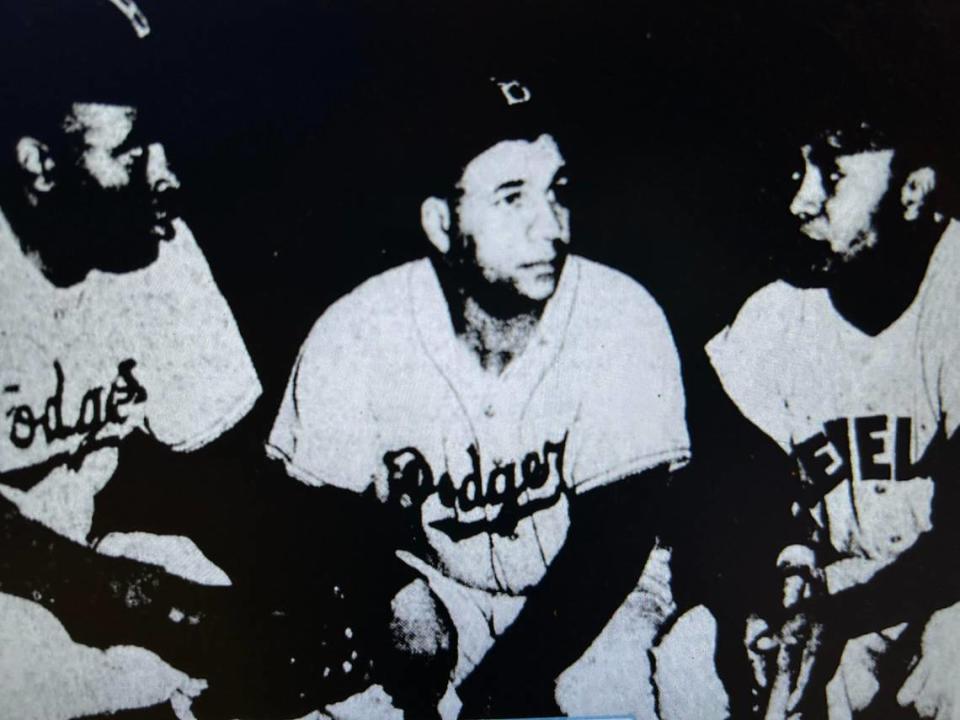

When Jackie Robinson brought his barnstorming all-stars to Devereux Meadow that October, he qualified as the most-famous player to sink cleats in its dirt — partly because he batted .328 in the majors that season, but more because he loomed to superhuman size for breaking baseball’s color barrier.

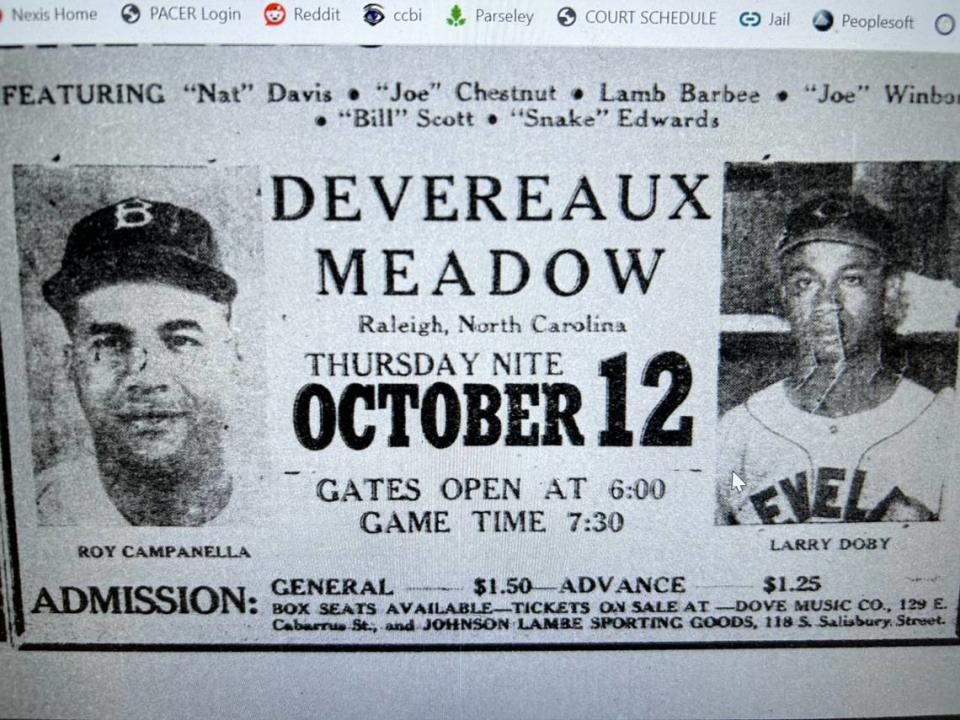

The all-stars beat the Raleigh Tigers 16-2 that night, a crazily lop-sided game that newspapers scarcely bothered to cover other than to mention the big names: Roy Campanella, Larry Doby ...

But that forgotten contest stands out for reasons unrelated to balls and strikes.

Special arrangements

Normally, the Raleigh Capitals played at Devereux — a sad-sack team that finished in seventh place, notable only for having the real-life Crash Davis on second base. And normally, their fans in the grandstand were white.

Normally, the Raleigh Tigers played 2 miles away at Chavis Park, an even more humble diamond. And normally, the fans in the bleachers were Black. Neighborhood kids could watch for free if they brought water for the players.

But Jackie Robinson’s achievement was so large, and his fame so large, that his all-Black team and the all-Black Tigers competed in the Raleigh park that normally restricted them. On that night, special arrangements had to be made to seat white fans.

It begs this question:

“Did Jackie Robinson break the color barrier in Major League Baseball and also break the color barrier in Raleigh’s Devereux Meadow?” asked Ernest Dollar, Raleigh’s director of museums. “I would love to know the answer.”

That answer appears to be yes, as The Carolinian trumpeted the news across its Oct. 7, 1950 front page:

RALEIGH PARK JIM CROW ENDED

The decision, strangely enough, came via the local Board of Education, four years in advance of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. The Carolinian declared a racial barrier had fallen “with a resounding crash.”

See Raleigh’s baseball past

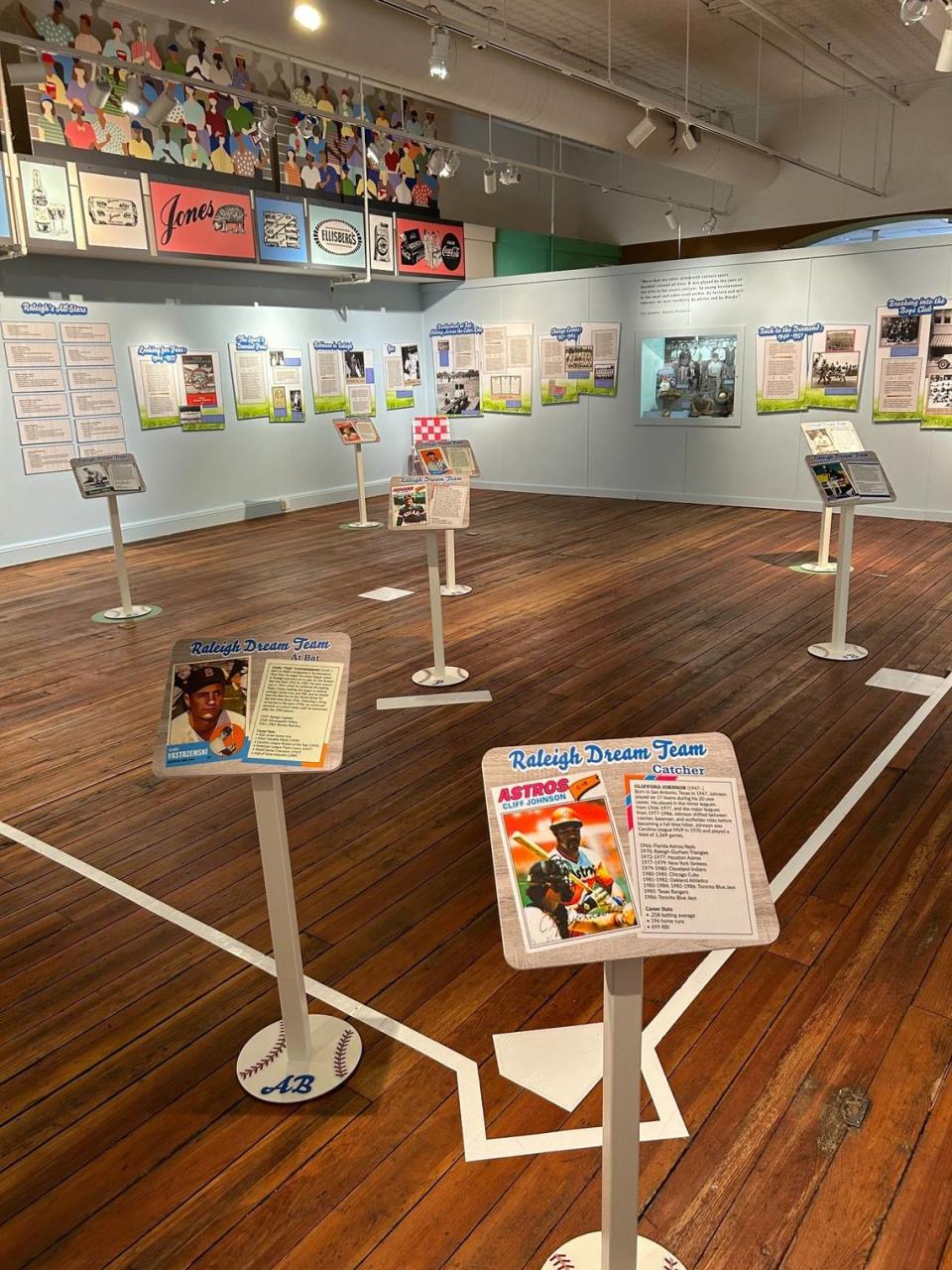

Robinson’s all-stars resurfaced this summer as part of the “Diamond Days” exhibit at the City of Raleigh Museum, which aims to show the Oak City is far from a baseball-free town despite lacking a pro team since 1972.

Not only did Hall-of-Fame Red Sox giant Carl Yastrzemski play here, knocking home runs onto what is now Capital Boulevard, but so did Hank Greenberg, hitting .314 when he was only 19.

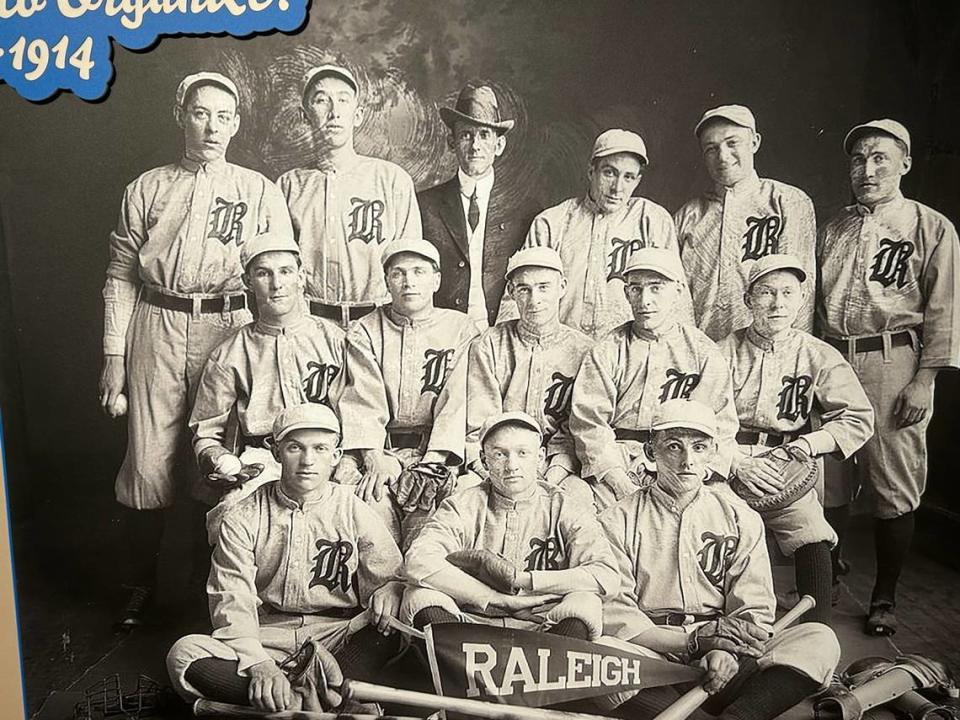

Raleigh embraced the sport shortly after the Civil War, when Union soldiers would challenge all comers from the outlying towns. The museum walls are lined with black-and-white portraits of the Raleigh Capitals of 1914, and the St. Augustine’s College squad of 1949 — all of them squatting on one knee and greeting Raleigh from another century, grinning under their jaunty caps.

But Robinson and his traveling all-stars conjure the most powerful picture, especially considering The N&O interviewed him after the game while he practiced his golf swing at Devereux Meadow, driving balls deep into the outfield.

The reporter that day hardly bothered with the all-stars game, drilling Robinson about his shaky status in Brooklyn.

“The fans in Brooklyn have been wonderful to me,” he told the N&O between swings. “But you’ve got to be ready to move at any time in this business, and it wouldn’t surprise me at all if I’m with another club next year.

“It won’t be the Giants, though,” he continued, throwing some shade toward a rival manager. “I’d object to such a deal. (Leo) Durocher and I had our differences when he managed at Brooklyn, and they still exist. I know this feeling is mutual, too. No, I wouldn’t care to play with the Giants.”

Robinson’s all-stars moved on that day, playing Durham, then Greensboro, then Charlotte — all mostly meaningless games built on star power.

But the fact that he walked here inside a stadium destined for the wrecking ball, waving to a crowd that wouldn’t let him eat at a lunch counter downtown, elevates us as a city — lending greatness by association.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports