Randy Johnson Steps Behind the Camera

Photographs: Chris Loomis, Getty Images; Collage: Gabe Conte

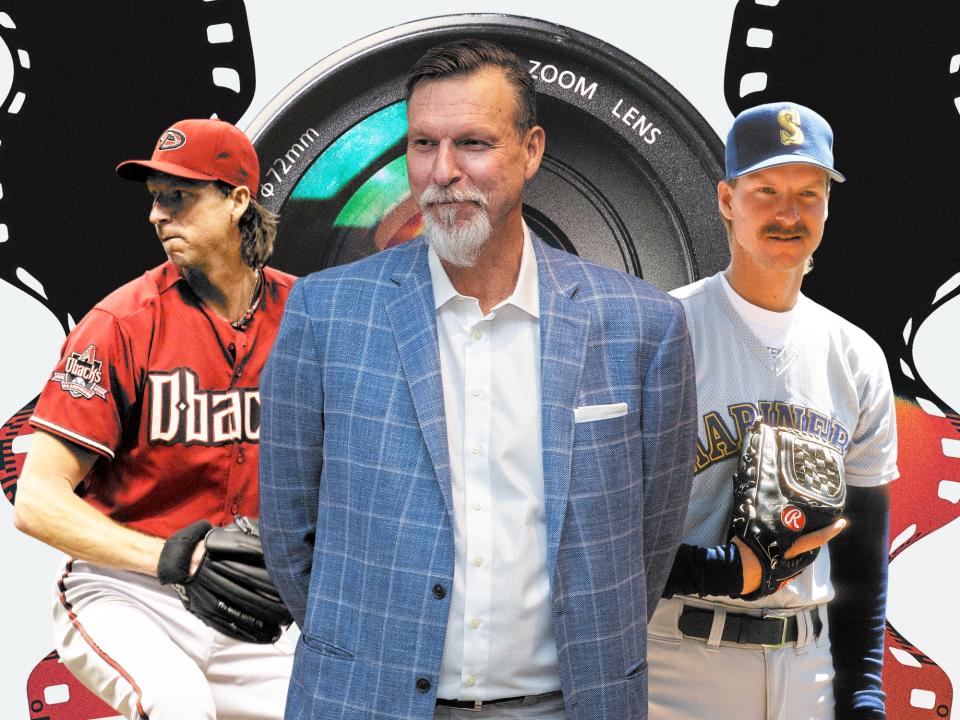

Picture Randy Johnson. What do you see? The mullet, the mustache, the electric arm. A snarling oak tree planted atop a mound. Lefthanded batters would sooner take the day off than risk a 100-mph gust of wind behind the ear. Even righties never dug in too deep. He was an icon at the last moment baseball players could be icons.

But here comes Randy Johnson, 15 minutes early, striding towards the double doors of the Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts. He wears a short-sleeved button down, blue jeans, Vans Old Skools, and a G-Shock watch. His goatee’s turned gray and his mullet’s gone; now he wears his hair short and gelled into a side part.

In the 15 years since he hung up his spikes, Johnson has moved behind the camera: the man who’d spent a quarter-century on the mound, eyes and viewfinders trained upon him, has quietly built a second career as a photographer. At some point, all the great ones shift from player to persona. But these days, Johnson, 60 and a bit creakier for all of the miles, mostly looks like a 6’10” dad.

Mostly. He hasn’t seen me yet as I watch his arm stretch to the end of that impossible wingspan, up into the sprawl of the desert sky. The Big Unit takes a selfie.

We’re here because Johnson is mounting a new exhibition of his work: 30 shots of elephants, wildebeests, and portraits of locals from six different trips to Africa. (Later this spring, a hotel in Phoenix will be showing 50 of his concert photos: of Slayer, Elton John, Billy Joel, Metallica, and more.)

We take a seat in the center of the white-walled gallery. The Hall of Famer now wears hearing aids and talks loud, a giant’s voice that bounces off the high ceilings. He’s still a mountain of a man, but the rough granite has smoothed a bit. It wasn’t, he explains, all that rough to begin with. “That was something created by other people,” he tells me. “I didn’t sit in front of the media and go, ‘I’m intimidating.’ But other players did and so it just kind of snowballed. Then you might hear about it a little bit more and so you try to play into it; you try to be maybe a little bit intimidating.”

“If you’re nervous about coming up to the plate,” he continues, “then I already got you beat halfway.”

For a time, Johnson thought his first and only career might be as a photographer: he grins easily as he tells me of his time shooting for the Daily Trojan newspaper while studying photojournalism at the University of Southern California. His fastball was otherworldly then, but he had no control. His teammate Mark McGwire was USC’s star; Johnson still was a project. A music lover, he’d walked into the Daily Trojan newsroom and told the photo editor Jon SooHoo (who now is the Dodgers team photographer) that he wanted to shoot rock shows. SooHoo said sure, that his height might be helpful in the pit, and Johnson relished the gig. He remembers walking across the street from campus to the L.A. Memorial Coliseum, flashing his press pass, and getting in to see The Who. The Clash were opening that night. In February, he shared a shot from that concert to his 119 thousand Instagram followers: Joe Strummer wears sunglasses, a mohawk, and a sleeveless shirt open to his navel.

But photography took a backseat to the work of finding the strike zone after he was drafted by the Montreal Expos in 1985, he says, and he never really picked his camera up again until he left the game. “I kick myself,” he tells me. Think of the pictures he could have taken—in the dugouts, on the buses, backstage with his Seattle grunge friends soon to become legends.

In retirement, he’s made up for lost time. He studies photographers he loves, and then reaches out on Instagram to talk shop. He points to a shot from his first trip to Ethiopia and shakes his head. “It was a great experience, but something was missing,” he explains. He hadn’t done the preparation to be ready when the image presented itself. Johnson can’t help but see parallels between his onetime livelihood and his passion. “It was a matter of executing. You didn’t always execute. And sometimes you got away with it, sometimes you didn’t,” he says. “But it wasn’t gonna be for lack of effort, or lack of preparation.” Each trip back to Africa, he tracks his growth—still a pitcher jotting down batter tendencies and bullpen notes. “If you set the bar and strive to be better then you will eventually get better because you’re pushing yourself and not being complacent,” he tells me. “I do that with photography, and I did it with baseball.”

As a ballplayer, Johnson liked to pick the brains of team photographers and the guys at the magazine shoots, asking about film stock, camera settings, studio lighting, and shutter speeds. That’s how he met Michael Zagaris, a longtime Bay Area photographer—that and their shared love of rock ‘n’ roll. Zagaris remembers Johnson, then a Yankee, asking to come by his place to buy some of his shots of drummers—the Big Unit always had a drum kit. He tried to talk Zagaris into a friends-and-family discount. “Randy goes back into the clubhouse, and [Yankees Manager Joe Torre] goes, ‘Z Man, don’t give him a fucking deal. He’s making 20 million a year!’” Zagaris says. “Then he says, ‘Maybe I can get some pictures. Can you give me a deal?’”

There was a game in Oakland in the late '90s, Zagaris tells me, and Johnson hadn’t let up a hit. Before the 7th inning, Zagaris crouched behind the plate to snap some shots of the towering lefty getting loose. Johnson started waving his glove, but Zagaris didn’t know why. “Then the third pitch came and just whizzed by my ear,” Zagaris says. “And I’m like, ‘What the fuck?’ And he’s like, ‘Get the fuck outta there!’” The next inning, the A’s broke up the no-no. Years later, they were hanging out and Johnson brought up the story unprompted—Zagaris had to break the news that the photographer was him. “And he said, ‘No way. That was you?’” Zagaris remembers, laughing. “‘I buzzed that guy. If I knew that was you, I would have drilled your ass!”

Zagaris had heard Johnson studied photojournalism, but he’d never seen his work. When Johnson posted a photograph of a wild dog, Zagaris reached out to tell him that what he has can’t be taught. “That passion that drove him in baseball, it’s driving him now in photography. This is just who he is. He has a zest for life and for living and an innate curiosity,” Zagaris says. “He’s always been inquisitive and he’s still searching.”

The photos are much better than you’d expect from an old ballplayer—not high art, but good nonetheless. But it’s the taking as much as what is taken that draws me in. What does The Big Unit see in Africa? What is he looking for? He tells me his white whale is a straight-on black-and-white portrait of a massive bull elephant called a Super Tusker, whose tusks scrape the ground. Another pitching metaphor: that evasive shot, he says, is his “perfect game.” He didn’t throw a perfect game until he turned 40, he reminds me. We’re still in the early innings of his photo journey.

But as we talk, it becomes clear that something else has drawn Johnson back so many times. “When I’m in Africa, I don’t get noticed. Nobody knows who I am,” he says. “I’m just a big, tall guy with a camera that’s taking pictures.” He can move freely, chasing images on three-week trips. He’ll snap 20,000 photographs, waking up at 7 a.m. to look for big cats or head to villages to shoot portraits. There, he isn’t the fearsome lefty, the legend, the Big Unit. He’s just an exceptionally tall dude with a camera and the means to explore.

Johnson points me to his favorite shots that hang upon the gallery wall, but I ask if any of his old ones, from his college days or his playing career, have stood the test of time. There are just two, he says, that he’s deemed worthy to frame and hang on the walls of his Arizona home.

The first is from the early ‘80s. He was walking on campus one night, near Fraternity Row, and saw a dumpster in an alleyway with a Mini Cooper tipped in. He had his Pentax K1000 with him and snapped a photograph.

A lot of the negatives from that era were thrown away during one of the many moves—from Montreal to Seattle to Phoenix to New York to San Francisco and back to the desert again. But that Mini Cooper one survived. “It was in black and white,” he says. “Kind of timeless.”

The second photo is from the early '90s, when he was just getting going in Seattle. “I was single and on my own walking the streets at night during the offseason,” he remembers. It was snowing near Pike’s Place, and he was right by an old bookstand with his Pentax 67 film camera. “I got my back up against a wall with a wide-angle lens,” he continues. “You can see the guy stocking the magazine rack and that’s about three quarters of the viewfinder. Then the other bit is the sidewalk, the background outside, and a light pole.” Another man walked towards him in a trench coat and a big hat, and the slow shutter speed cloaks him in an eerie blur.

Both pictures come from before the first of his five Cy Youngs, before his life forever changed. Still, at 6’10”, even then it was a rare luxury to disappear. But with camera in hand in a dark alleyway or pressed against a wall on a snowy night, Johnson could be unseen.

The camera is a mirror, but it’s also a spotlight. Johnson tells me it’s changed the way he sees the world. Now, when he watches movies, he finds himself noticing every angle the cinematographer chooses. When he travels, or bikes, or hikes, or walks around town, he’s always scanning, looking for a perfect shot. “My eyes are a little bit more open,” he says.

He’d long been a subject, of stares and flashbulbs, of adulation and hate. He’d had to move more quickly then. His dinners would be interrupted; in New York, he’d be trailed by photographers hoping to sell a shot. These days, he can stand alone, focused on a job, hidden behind his camera. Hidden, at least, as much as a giant can ever hide.

I’ve spoken with athletes who explain retirement like a first small death. Johnson, though, says leaving the game wasn’t so hard for him. He misses the camaraderie and the competition, sure. He loved that you could put all of yourself into something and then let it go, because you had to do it over again five days later. “I mean, I played 22 years. The gamut. Four years in the minor leagues. Three years in college. I got my fill. Do I miss it? Yeah, there’s certain things I miss,” he says. “But my body… you know, I just had full knee replacement. I have a torn left rotator cuff that I hurt the last year of my career that’s probably just scarred over now. I had three back surgeries. So, it ran its course. My body broke down because of the demands. But I wouldn’t want it any other way.”

But he doesn’t view life in the past tense. He’s got more to see, more photographs to take. “As soon as my knee heals, I’m not too old to pack a bag,” he says. “If I could live over in Africa in a village and be where I want to be for a month, I would do it.” Backpacking across Europe, maybe. Picture it: the Big Eurail Pass. “Maybe for a year go do that. I mean, that’s living the life. That’s seeing the world,” he continues. Johnson leans back in his chair. Now he’s smiling again. “And I would like to do that with a camera.”

Originally Appeared on GQ

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports