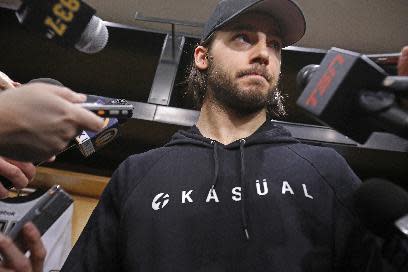

Kris Letang: 'I'm worried every day' but unafraid to play after stroke

You almost don’t recognize him as he walks through the dressing room. Is that Kris Letang? Gone are the long locks that used to spill out of his helmet. He looks young. But ask why he cut his hair, and he laughs.

“Getting older,” he says. “I’m just getting old.”

The man has aged years in months.

He had a stroke at 26 – rare for anyone, let alone a professional athlete. He sat out 10 weeks. He returned to play for the Pittsburgh Penguins, after doctors assured him hockey did not cause the stroke and would not increase his chances of another. He pushed himself harder than usual over the summer, anyway, just to make sure his body could handle it.

He’s 27 now. He feels good. He’s entering an eight-year, $58 million contract extension. He has a new coach, Mike Johnston, who preaches puck possession, and a new defense partner, Christian Ehrhoff, who can skate and pass, and both suit his skill set. Yet to say he’s back to normal isn’t quite right.

This is a new normal for him. He is dealing with the migraines he has had since childhood, monitoring himself for stroke symptoms, taking medications for both issues every day and talking to doctors often – all while trying to regain the form that made him a finalist for the Norris Trophy as the NHL’s best defenseman two seasons ago.

He isn’t afraid to play hockey. He’s eager to play hockey.

But that doesn’t mean he isn’t afraid.

“Yes, I’m worried every day,” Letang says in a matter-of-fact tone. “The percentage of that happening was point zero one percent. So the percentage of that happening again for me is still there. It happened once. Why not twice? That’s always in the back of my mind.”

* * * * *

The morning of Jan. 29, Letang’s wife, Catherine, woke up and found him on their bedroom floor. He was awake but couldn’t function. They didn’t realize what was going on. No one did. He felt well enough to fly with the team later that day, but not well enough to play against the Los Angeles Kings on Jan. 30 or the Phoenix Coyotes on Feb. 1.

“We didn’t know what it was,” says goaltender Marc-Andre Fleury. “We were kind of laughing at him. At first, it was no fear. And then when you find out …”

Pause.

“It’s humbling, I guess you would say.”

A series of tests showed Letang had a stroke.

Doctors explained how rare it was to have a stroke at his age – .01 percent. They told him they didn’t think he needed surgery to close a hole in his heart, a common condition and possible cause. They said he would be able to continue his NHL career.

Still, a stroke is a stroke. Letang and his wife have a son, Alex, who will turn 2 in November.

“It was pretty scary,” Letang says. “I was not sure I was going to play again. For that two months that I couldn’t do anything, it was perfect to just reflect on life and making sure I’m taking the good decision going forward. I have to respect the fact that I have a family, too, and if I want to put my life at risk if I’m going back to play.”

Even though the doctors insisted the risk was no greater on the ice than it was on the street, it was hard to overcome the fear – not just for Letang, but for the people who cared about him. Doctors cleared him to play long before Ray Shero, the general manager at the time, would let him return to the lineup April 9 against the Detroit Red Wings. Letang had to bug him.

“You want him to play hockey and do what he loves best – being out there on the ice, being with the guys,” says winger Pascal Dupuis. “At the same time, you don’t want his personal life to suffer, or …”

Pause.

“Something bigger.”

Letang played the final three regular-season games and all 13 of the Penguins’ playoff games, logging as much as 27:56 of ice time. He watched Shero get fired, then coach Dan Bylsma. He watched Jim Rutherford take over as GM, then Johnston as coach. He watched Ehrhoff sign a one-year deal as a free agent.

He went beyond his usual off-season workout routine – already considered freakish – to make sure no one had any doubts, including himself. He was followed by a neurologist.

“He’s a very determined guy,” Rutherford says. “He wants to be successful. It was just a matter of knowing he was healthy, which we know he is, and getting ready to come in and play under a new coach. I was impressed.”

Smile.

“He came in with a new haircut. I have to be careful how I say this, because I don’t have anything against long hair, but he looked like a real pro. He looked like he was ready to go.”

Letang makes it clear that he liked the previous coaching staff. But he seems best in a system like Johnston’s with a partner like Ehrhoff.

Bylsma wanted the puck up the ice as quickly as possible – fire it up the boards, chip it into the zone, crash on the forecheck. It stretched things out. Johnston wants to hold onto the puck and attack as a unit.

In theory, there should be fewer times when the Penguins throw the puck up the ice only to lose it, fewer high-risk plays that lead to turnovers, more time in the offensive zone and less time in the defensive zone.

Letang and Ehrhoff should be able to play off each other. In a preseason game Wednesday night in Detroit, Ehrhoff held the puck at the Pittsburgh blue line. He didn’t like what he saw in the neutral zone. Instead of chipping the puck ahead, he regrouped and passed from left to right to Letang, who waited, waited, found a seam and hit Sidney Crosby coming up the left wing.

“Possession is fun for me, because we’re not playing a waiting game to see if we’re going to retrieve the puck or not,” Letang says. “We’re proactive. We dictate the pace that we want. … I’d rather be in possession than chasing.”

Johnston also wants his defensemen to jump into the play depending on possession. If the Penguins have the puck under pressure, be careful. If they have solid control, go. Just don’t loiter deep in the offensive zone. Johnston says an attacking defenseman has one attempt at a quick strike. If it doesn’t work or the Penguins lose the puck, get back.

“I know he’s liking it,” Fleury says. “That’s for sure. He’s got more time with the puck, more room to skate, and he’s so good at it, so fast.”

Letang has come a long way since Jan. 29, and he has the potential to go much further.

“Last year, we talked,” Fleury says. “A few games [after returning from the stroke], maybe he was a little worried. You never know what could happen. But he got confident. He looks very good. He looks like himself right now.”

But there are still some things we don’t see.

* * * * *

Letang comes off the ice after practice Tuesday in Detroit with a headache – a debilitating, shut-it-down headache. But at least he knows it’s just another migraine, not another stroke. He says they are not related.

“I kind of can tell what’s the difference now,” Letang says. “There’s different things that happen during the day that I know it’s not normal for me.”

Letang knows the danger signs – trouble with balance, trouble with vision. He knows they might come if he’s really tired, so he tries to get a lot of sleep and keep himself fresh. He takes his medications. Every time he doesn’t feel right, he talks to a doctor and makes sure he’s OK. There is always one nearby. The Penguins take their doctors on the road.

“My life is a little different with it,” Letang says. “Obviously there is some change. But like we talked about at the beginning when it happened, I’m just going to get used to it. That’s the process. It’s a permanent damage that was done to my brain. I just need to deal with it, make sure I’m comfortable with it.”

He is comfortable with it. As comfortable as he can be.

“I would have never stepped on the ice if I didn’t feel comfortable,” Letang says. “If you ask around, hockey is my life. That’s what I love to do. [But] if I was not comfortable coming back, I would have never taken that chance, especially with my family. I feel 100 percent.”

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports