As one of our own, Whitey took us all from southern Illinois to Cooperstown

Before he made his major league debut two weeks ago in Los Angeles, St. Louis Cardinals center fielder Victor Scott II was asked by a reporter to describe his style of play to fans at home who might not have had a chance to see him move through the minor leagues.

“I guess I would describe it as Whiteyball,” Scott answered. “I’m just a new age Whiteyball.”

He was born on February 12, 2001, nearly 11 years after Dorrel Norman Elvert “Whitey” Herzog managed his last game in the big leagues. And still, more than two decades later, standing in the same Dodger Stadium clubhouse where Jack Clark and his teammates celebrated a home run which won the pennant in 1985, Herzog’s name could be invoked to instantly and definitively bring to mind a style of baseball which defined not only the rollicking 1980s but also the very identity of a team and its city throughout.

Whitey Herzog died Tuesday at age 92, and even still his influence courses through some of the game’s most vibrant and exciting players.

The Runnin’ Redbirds won three pennants and the 1982 World Series championship under Herzog’s watch and through the force of will of his singular vision. That he had both the talent and conviction to build a dynastic team would be rare enough, but it was the good fortune that allowed him to do so with his hometown team that made Herzog an undeniable legend.

Born and raised in New Athens, Herzog was a star athlete in both baseball and basketball before signing with the New York Yankees in 1949 and earning his lifelong nickname due to his resemblance to Yankees pitcher Bob “The White Rat” Kuzava. He served in the United States Army Corps of Engineers during the Korean War and would go on to play eight years in the majors for four teams, primarily as an outfielder.

He posted a respectable .257 batting average in his playing career, but stole only 13 bases and was caught 18 times. Whatever speed he lacked on the basepaths as a player, he sought voraciously as an executive.

Herzog won his first World Series championship as an executive for the 1969 Miracle Mets, working as the team’s director of player development. After being passed over in favor of Yogi Berra for the Mets’ manager job following the death of Gil Hodges, he would have brief stints in both Texas and with the California Angels before managing the Kansas City Royals between 1975 and 1979.

Crossing the state in 1980, then-owner August A. “Gussie” Busch Jr. gave Herzog control of the Cardinals as both general manager and field manager. The 1980 Winter Meetings would prove to be one of the most hectic in baseball history, and the action all centered on Herzog’s unflinching conviction in his ability to move pieces around.

As the baseball world converged on Dallas’s Loews Anatole Hotel, the late Hall of Fame baseball writer Rick Hummel of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch was delayed in his travel. Finally arriving, as Hummel relayed the story years later, he spotted an agitated Herzog in the lobby, who snapped, “where you been, Hum? I got deals to make!”

And oh, deals he made.

On December 8, in a staggering 11-player deal, Herzog and the Cardinals acquired legendary closer Rollie Fingers from the San Diego Padres. One day later, December 9, he swung another deal, acquiring Bruce Sutter from the rival Chicago Cubs with visions of constructing an impenetrable bullpen fortress to protect the back end of games.

Fingers, though, had no intention of splitting up the workload, and made it clear to Herzog that he expected to close every game for whichever team he played. Herzog then found him a new team, passing Fingers on to Milwaukee just four days after acquiring him, on December 12, along with Hall of Fame catcher Ted Simmons in exchange for a package of four players headlined by David Green.

It was a preposterous series of moves that never should have worked and would be impossible to imagine in a modern context. Two years later, though, the 1982 Winter Meetings would be a celebration of the newly crowned champion Cardinals, defeating the Brewers with Fingers and Simmons looking on from the opposing dugout.

If one thing ever defined Herzog’s Cardinals, it was moving fast. Faced with lightning-quick turf and cavernous dimensions at Busch Stadium, he simply worked to acquire players who could put the ball on the ground and sprint after it, bounding around the base paths as the ball bounded on the turf.

In a memorable scene from 1981, Herzog hauled Garry Templeton down from the dugout steps after Templeton directed an obscene gesture toward a group of heckling fans. That winter, he sent Templeton to San Diego in exchange for Ozzie Smith, the final and one of the most vital pieces of the 1982 champions.

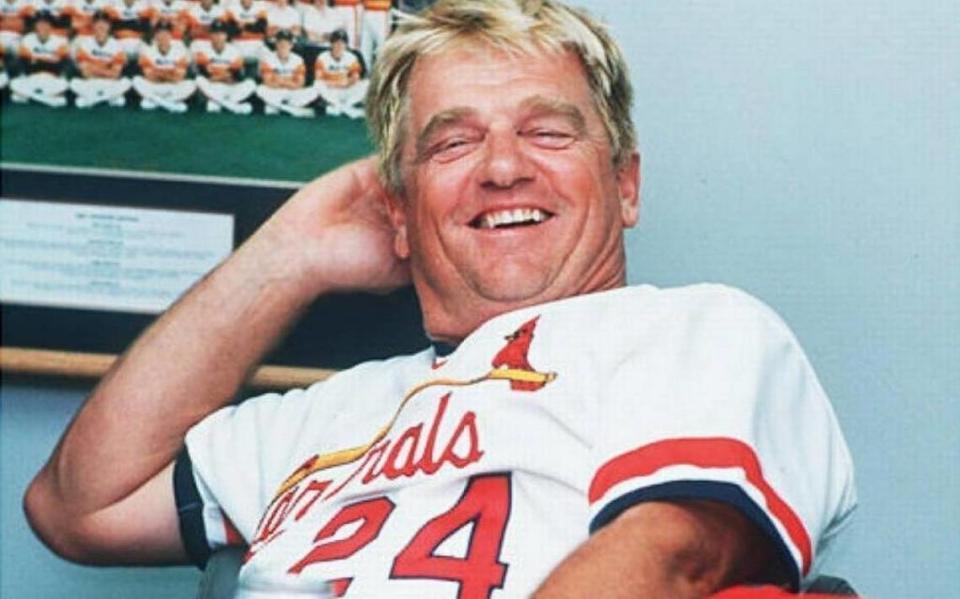

Those champions defeated the slugging Brewers – Harvey’s Wallbangers, as they were known – in seven games, and a photo from the postgame celebration showed Herzog at his office desk, laughing broadly, a can of Bud Light open on the desk. Just one week ago, at the 2024 Busch Stadium home opener, he filed into his seat in a box and acknowledged a roaring crowd with a wave of his hand, undeterred by the cold day.

In between was an induction to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2010 and the subsequent retirement of his number 24 that summer. There were also countless trips to the ballpark, to spring training, to events and signings and gatherings and innumerable galas, some at which he was celebrating and some at which he was celebrated.

Still, there was that delirious man at his desk with a cold beer, seemingly besotted by the joy of taking his team – his team, his town’s team – to the promised land. It’s the way so many remember him because it’s the way so many themselves were in the moment. And if Whitey Herzog could go from New Athens to Cooperstown and everywhere in between, why couldn’t everyone else?

It’s that mark on the game which makes it possible to find out, and it’s living – and in the lineup – still every day.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports