An old-school Las Vegas bookie takes on a new era of sports betting

LAS VEGAS - It was 1:30 a.m., and Chris Andrews, sportsbook director for the South Point hotel, was asleep at home when an unfamiliar customer approached a betting window at the casino, wanting to wager 300 grand on the 49ers to beat the Chiefs in the Super Bowl. A supervisor woke Andrews to approve the bet, only for the customer to realize he didn’t have enough cash on hand.

Andrews got to work Friday morning eager for updates on “Mr. 300,000,” who returned about an hour later carrying a cone from the hotel’s ice cream shop as well as the money, converted to South Point chips, and this time opted to bet $243,000 on San Francisco. Andrews chatted briefly with the man before wishing him luck.

Andrews and his right hands at the South Point, Jimmy Vaccaro and Vinny Magliulo, have a combined 147 years of experience taking bets in Nevada - and a philosophy that dates from a time when relationships and a human touch ruled an industry that has rapidly changed. For them, bookmaking remains a blend of art and science, in which odds are adjusted depending on what respected “wiseguys” are betting. That means being able to size someone up in an instant and know whether they’re sharp or square.

Around town, sharp money mostly backed San Francisco at this year’s Super Bowl, while recreational bettors heavily favored Kansas City. Yet Andrews suspected “Mr. $300,000” was a square, albeit an exceptionally deep-pocketed one, and his wagering history supported that. He had lost about $22,000 to the South Point last Super Bowl, a colleague relayed to Andrews. In other words, the colleague said, “He’s just a gambler.”

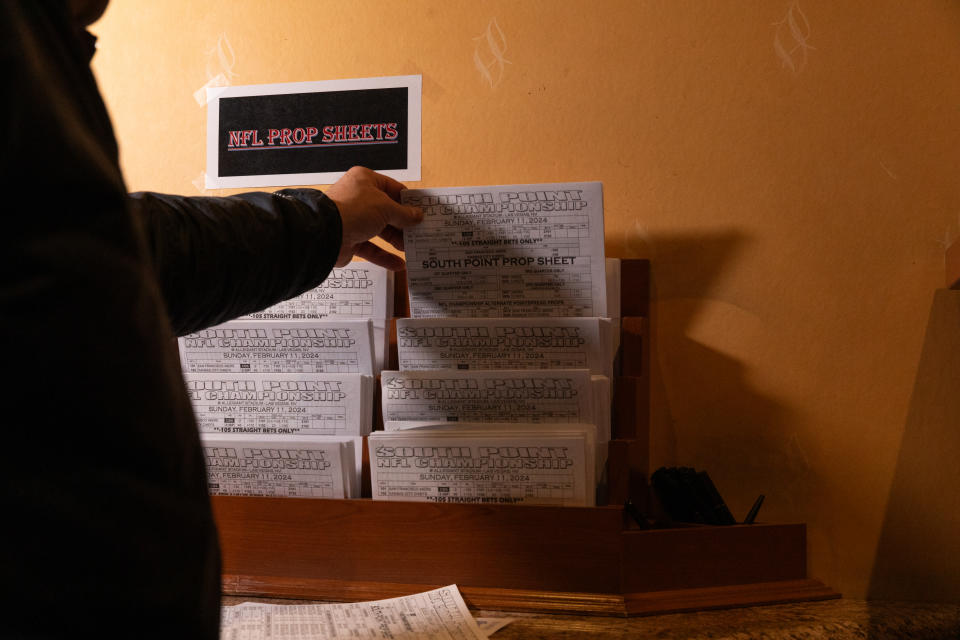

Getting a six-figure bet from a square “is like finding a diamond ring,” Vaccaro quipped in the sportsbook’s back office, where the South Point gave a reporter a rare opportunity to observe some of Las Vegas’s most respected bookmakers in action during their busiest weekend of the year.

The South Point doesn’t have the bottomless advertising budget needed to get Peyton Manning or Jamie Foxx to hawk its sportsbook. It doesn’t pay media stars like Bill Simmons and Pat McAfee to promote elaborate same-game parlays that benefit the house. Instead, the hotel’s distinctly old-school sportsbook, located about six miles south of the Strip, lures customers with reasonable odds, friendly service - and $1.50 hot dogs.

One of the last family-run hotels in town, it’s owned by Michael Gaughan, 80, who sat in the sportsbook’s office two days before the Super Bowl with a hint of mustard on his lower lip from a lunchtime frank. He enjoys hanging out there, seated next to a sign on the mini fridge that reads, “Do not drink the Dr. Brown’s root beer. They are for Mr. Gaughan only!” The fridge also contains a jar of Grey Poupon that Andrews keeps for a professional bettor who once complained that the hotel only serves yellow mustard.

Nationwide, the vast majority of sports betting now occurs online, but Andrews said his sportsbook does roughly three-quarters of its business in person, while still managing to take more bets than any operator in the state.

Marveling at the sight of thousands of bettors passing through the casino to wager on the Super Bowl, Andrews reminded Magliulo, “We don’t do it with advertising and other sh--. Value, value, value. That’s our thing.”

Gaughan supports anything that can boost foot traffic, such as serving $2 Budweisers on NFL Sundays or Andrews’s idea to offer -105 odds on the Super Bowl point spread instead of the standard -110 - roughly a five-dollar discount on every $100 wagered.

Ahead of Vegas’s first-ever NFL title game, greed was a frequent topic of discussion in the back office. Corporations “want to kill the golden goose yesterday,” Gaughan said, grumbling about a hotel on the Strip charging $160 for valet parking that weekend.

Five years ago, some Nevada casinos feared that the spread of legal sports betting would threaten their bottom line. Now business is booming here like never before. Nevada took a record $185.6 million in bets on the Super Bowl - more than any of the 37 other states where sports gambling is regulated. Andrews had expected to handle around $10 million of that.

But while sports betting might be more popular than ever, Andrews and his peers are dismayed by much of what the industry has morphed into: shrieking ads, deceptive promotions, astonishing margins. They vent about the “European model” of bookmaking that’s taking hold across the country, in which customers who show winning tendencies are aggressively limited on how much they can bet, sometimes down to pennies.

“It’s not gambling,” said Richie Baccellieri, a former South Point bookmaker who now works at the downtown hotel Circa. “Everybody just wants to fleece the customer.”

The South Point welcomes big bets from sharps so that it can refine its odds accordingly. Last weekend, Bill Krackomberger, a baby-faced, heavyset pro bettor who wears Kangol flat caps, showed up to bet several thousand dollars on Super Bowl props, which involve player and team statistics. Magliulo and Andrews spent a few minutes schmoozing with him and offered to comp a meal.

“This is the old Las Vegas,” Krackomberger told The Post. “I beat them every Super Bowl, and they still want to take care of me.”

- - -

Taking bets since grade school

Andrews, Vaccaro, Magliulo and several supervisors occupy a small office adjacent to the betting counter. The walls are covered with memorabilia from Andrews’s beloved childhood team, the Pittsburgh Steelers, as well as a poster from the 1939 comedy “The Day the Bookies Wept,” about a racehorse that wins by drinking beer, and a letter to Andrews from Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.) , the late U.S. Senate majority leader. Congratulating him on joining the South Point, in 2016, Reid wrote, “The impact of your work in our community is admired and appreciated.”

Andrews, 67, sits in the middle of the office. Two of his four computer monitors display incoming bets, color-coded by dollar amount. He faces a grid of nine mounted TV screens, one of which was dedicated, until moments before kickoff, to Turner Classic Movies. While booking millions of dollars, Andrews and his confidants got much more animated debating the acting performances in “Roman Holiday” than they did over any oddsmaking decision.

Andrews learned the game, and the customer service that comes with it, from his uncle Jack Franzi, a revered sports bettor who also wrote a little action in the back of a candy store. Andrews was booking classmates by fifth grade and taking bets in the stands when his high school football team defeated Joe Montana’s squad.

When Andrews was 14, Franzi was charged with interstate gambling after an 18-month investigation, during which the FBI photographed him and his nephew at sporting events, out to dinner and playing miniature golf. After a judge dismissed the case, Franzi moved to Las Vegas, and Andrews followed him after graduating from Robert Morris University. He spent his first year in Vegas making $45 a day filling out triplicate betting tickets at the Stardust, the questionably run establishment depicted in Martin Scorsese’s “Casino.”

About 25 years later, Andrews describes in his memoir, “Then One Day…,” a former FBI agent approached him and his uncle at dinner and told Franzi that he used to eavesdrop on his calls and copy his bets, conceding, “It was the best two football seasons I ever had!”

Vaccaro, 78, works out of a room in a corner of the office that includes a desk and a massage chair. A slender man with white hair combed back, Vaccaro used to run a glitzier sportsbook at the Mirage, where he handled “some of the biggest bets probably ever taken in the U.S.,” said Matthew Metcalf, former director of Circa’s sportsbook.

Vaccaro - whose older brother Sonny signed Michael Jordan to his first sneaker deal at Nike - is now more of a casual consigliere to Andrews, his friend since childhood. During down moments at the sportsbook, Vaccaro slips away to the hotel’s spa for a steam, soak and quick snooze. He knows seemingly every South Point employee by name, though he also affectionately refers to anyone younger than him, Andrews included, as “kid.”

Magliulo, 66, resembles a younger Robert De Niro, as others have noted. He previously ran the sportsbook at Caesars Palace and has known Andrews since the late 1970s. When they deliberate, Magliulo grabs a chair across from Andrews and speaks in serious-sounding hushed tones - about how they might adjust a line, or whether cream of mushroom is a stronger lunch option than chicken noodle.

Like Vaccaro and Magliulo, Andrews got to know Gaughan early in his career. Gaughan’s father, Jackie, was the first to put a sportsbook inside a Las Vegas casino, and Michael got his gaming license at 25.

The South Point reflects its owner’s old-fashioned sensibilities. “Mr. Gaughan hates modern,” general manager Ryan Growney said. Music, booming day and night in many casinos on the Strip, is less noticeable inside the South Point. Its nine reasonably priced restaurants lose about $1.5 million each month, according to Growney.

Asked about some national sportsbooks profiting as much as $30 for every $100 wagered, while the South Point holds about $5 for every $100, Gaughan told a story from early in his career. Many riverboat passengers, he noticed, spent much of the trip sitting around glumly after going bust on slots. Gaughan lowered slot hold percentages so customers only ran out of money as their boat was docking.

- - -

Following the money

Andrews and his colleagues spent little time in the days before Sunday analyzing football while adjusting their odds. “We’ll let the money dictate what we do,” he said.

As his (much younger) colleague Ashley Eck put it, “feel” can be more important to the job than number-crunching. The biggest challenge isn’t coming up with odds, but rather adjusting those potential payouts as money streams in, incentivizing or discouraging certain bets so that, ideally, the house comes out ahead no matter what.

While many of the biggest online sportsbooks set and adjust odds using algorithms and automation, some Nevada operators still make and move their numbers manually. “The computer doesn’t tell us what to do,” Magliulo explained. “We tell it what to do.”

Andrews and Eck spent a few days ahead of the Super Bowl setting their few hundred prop bets. DraftKings, by comparison, offered 1,000 or so Super Bowl props. Major national operators also depend on same-game parlays, allowing customers to stack props for the chance at a bigger payout. Though SGPs are much more favorable to the house, the South Point doesn’t offer them.

The South Point opened Super Bowl betting with a few glaring miscues, like pegging the odds of 49ers running back Christian McCaffrey scoring a touchdown at -400, meaning a $400 bet only stood to return $100. Professionals hammered the opposite side of that wager, moving the odds. “The wiseguys were all over us,” Andrews said. By gametime, a bet on McCaffrey finding the end zone (which he did) paid nearly twice as much.

Super Bowl Sunday was all hands on deck. Gaughan’s son Brendan - the former NASCAR driver - and grandson John manned two of the sportsbook’s 10 ticket-writing windows. Supervisors arrived at 4:30 in the morning. By kickoff, about 6,000 fans had come for free watch parties throughout the hotel. All 138 armchairs in the sportsbook had been occupied for hours.

Andrews, with football-field socks underneath his Skechers, started fidgeting for the first time all weekend minutes before the game started. “I can’t tell if I’m always nervous or never nervous,” he said. The house stood to lose somewhere in the low six figures if San Francisco won and the total score was under 47.

Earlier, Andrews and Magliulo had joked about squares’ willingness to bet on the opening coin toss, even at odds worse than 1-1.

“What’s wrong with people?” Andrews asked.

“Instant gratification,” Magliulo replied.

Now, Andrews yelled an expletive when the toss landed on heads, which, for whatever reason, bettors always seem to favor. He, Magliulo and Vaccaro watched the rest of the game stoically, while their colleagues enjoyed a spread of chicken wings, pizza and subs. A few staffers discussed their own bets on the game, something Andrews said he gave up long ago. (“I never want to be in a position where I have to choose between rooting for myself or the joint.”)

During overtime, with Kansas City down 22-19 and just a few yards from San Francisco’s end zone, Andrews remembered that teams don’t attempt an extra point after a game-winning touchdown in OT. That meant the final score was 25-22, exactly the total the South Point had landed on. Thus, every customer who bet a “teaser” - a notoriously unwise combo bet that involves getting +6 or more on one team to win, paired with an “over” or “under” total score prediction - got paid.

Half an hour after the Chiefs raised the trophy, customers were still waiting in long lines at the sportsbook to collect their winnings - or bet on next year’s NFL champion.

The South Point ended up taking slightly less on the Super Bowl than the $10 million Andrews projected. But despite getting wiped out on teasers, the house came out ahead on the game and did even better on props. Just as important, many sports bettors migrated to the pit, where the blackjack tables were full deep into the night.

“Mr. Gaughan was happy,” Andrews said.

Related Content

Haley’s nearly all-White high school lacked lessons of racism, some say

They found spiritual joy. They won’t have it taken away.

He was born at home in D.C. Now his parents have to prove he’s theirs.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports