As North Wilkesboro revels in its return to NASCAR, another NC track awaits revival

A punk-rock owner and a lobbyist and a reporter all rumble onto hallowed ground. They’re in a Lamborghini SUV. All black. Windows are down. Sunglasses are on. It’s a Monday afternoon in May, and the odd trio is idling on the backstretch of the famed 1.017-mile oval at Rockingham Speedway — a racetrack intent on pulling itself out of its past.

“You ready?” Dan Lovenheim asks.

His two passengers gulp down nerves and feign confidence. Lovenheim, meanwhile, shifts his car into sport mode, breathes in a lung’s worth of nicotine out of his neon green vape and sheds a charismatic smile.

“Hold on.”

GRRRRRRRRR—

His engine roars to life.

And for a few moments, as he circles his speedway’s turns at 120 miles per hour, something else roars to life, too:

The possibility of Rockingham’s resurrection.

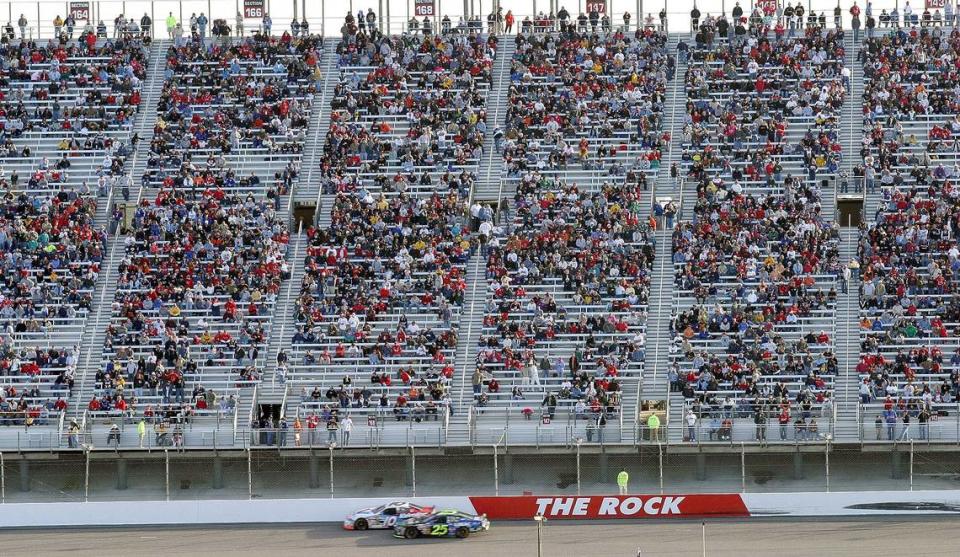

As recently as two decades ago, and as long ago as 1965, Rockingham Speedway heard these sounds tenfold as a staple on the NASCAR Cup Series schedule. “The Rock” was a landmark for the state of North Carolina. A rite of passage for the sport of racing.

Through the ‘80s and ‘90s, the Cup Series descended on this town of just about 10,000 people twice a year — once immediately after the Daytona 500 in the spring, and another time in the fall, so late in the season that some legends clinched championships there.

But time caught up to the racetrack. The facility changed ownership groups three times between 1997 and 2004, and fan support and its fate worsened with every acquisition. By the fall of 2004, the track was owned by Speedway Motorsports and had its dates on the NASCAR Cup Series schedule moved to other venues in new markets out west or up north.

The sport’s top series never returned. The speedway fell into relative disrepair. Richmond County, its surrounding municipality, suffered economically. Culturally, too. (You might’ve heard this story before.)

Nineteen years later, though, here Lovenheim sits, beating against time’s unrelenting current, representing Rockingham’s closest shot at revival in decades.

He might not be your conventional racetrack owner. He lives in Raleigh and owns nightclubs throughout the state. He drives flashy cars and parks them where he pleases. He wears black rings and silver jewelry, has bleach blonde hair and black-glitter-painted nails. He seems to see the world through a unique lens of youth and wisdom and ambition — making for the kind of vision that led him to purchasing this racetrack when he did in 2018.

But there’s a reason behind his optimism for the racetrack’s revival, of course. There are two reasons, actually.

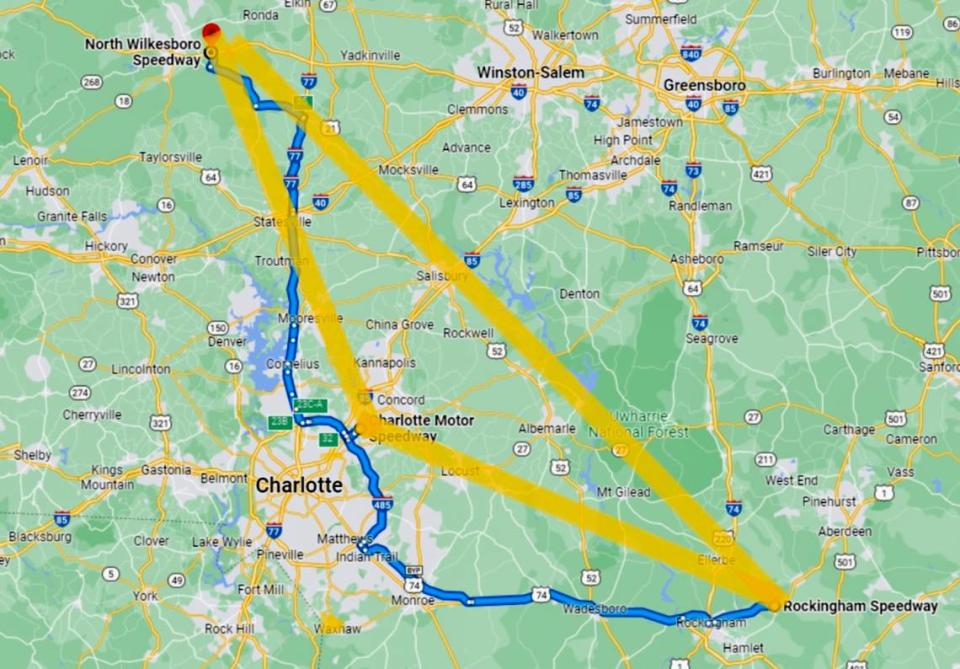

The first is that Rockingham lies close to Charlotte and North Wilkesboro. Its rural, south-central North Carolina location makes it a point of what Lovenheim calls the “golden triangle of racing.” Racing roots of moonshine and small-town Southern Americana began in this triangle — and this sort of return is something NASCAR fans are hungry for, Lovenheim says.

The second reason is a bit more personal. And that’s this: He’s been a mechanism for revival before.

He’s done so, even, with his own life.

Finding North Carolina on a motorcycle

Ask Lovenheim what brought him to North Carolina, and he’ll shrug.

“Technically a 1979 Volkswagen …” he might joke.

The actual story, per his retelling, is a bit more revealing than that.

In 1998, Lovenheim hit the road. The Rochester, New York, native was living in Buffalo at the time and decided to leave for “myriad reasons.” He hopped on a motorcycle, lugged around a tent and a backpack and began a years-long loop through Interstate 15 and a few localities. He lived in the mountains of Colorado, he said, and in the woods of New Mexico, and beyond.

About a year into his travels, while he was on his way to a Rainbow Gathering — a loose-knit community of people gathering without a central organizer — in a Pennsylvania forest in 1999, a Ford 150 truck made an unexpected U-turn, and Lovenheim crashed into it at 70 miles an hour. The accident “shattered basically all of my limbs,” he says today, scrolling through a few photos of X-rays for proof. (“That’s my leg,” he says pointing to a photo that shows a titanium rod bolstering his femur in his right leg with lag bolts through the knee and hip. He did the same for photos of his arms. “I’m like in a rector set, bro.”)

After a number of ICU surgeries and recovering in his parents’ basement, he fearlessly hopped back on the road, this time in a Volkswagen bus. In 2000, something he still can’t quite articulate compelled him to settle in North Carolina — and he soon started to build something that would last. He opened his first club in Greenville, just off the campus of East Carolina, then began investing in a strip of land in downtown Raleigh called Glenwood South and brought a popular strip of nightlife to the state’s capital.

“You asked me why I came here, and there is absolutely no reason whatsoever,” Lovenheim said. “I came somewhere my family wasn’t. Knew no one. Had nothing. And twenty years ago, I decided to go make something awesome happen.”

In 2018, he acquired the racetrack in an attempt to continue his mission of bringing people together, of throwing parties. But he wanted to do so on a larger scale.

“It wasn’t necessarily the smell of the motor oil, for better or for worse,” Lovenheim said. “But again, I think that leads to the inherent flexibility that we’ve been talking about. … Don’t get me wrong, this is a speedway. It is called Rockingham Speedway. Its fundamental, primary use is as a speedway.

“That being said, the way in which it had been used for many, many years was two times a year, and pretty much mothballed in between. We’re trying to have this thing be an economic generator for 52 weeks a year — for us, for the community, for everything. And we’re well on our way to doing it.”

Rockingham can be North Wilkesboro 2.0

Lovenheim’s track record for building institutions is a proven one. But still: What exactly does “well on our way to doing it” mean?

It’s complicated.

Lovenheim said he and his staff are deep in the process of renovation. The expression Lovenheim used in mid-May is “90% of the way there.” The place completed a $3.5-million repave in December, which furnished some local media buzz. The catch fence has been mended. The grandstands are race-ready. The garage is clean and now has lights and a surround system, and it even hosted a small music festival earlier this year, Lovenheim said.

A little bit of work on the hospital still needs to be done. A few bathroom structures need to be finished. But, per Lovenheim: “With everything we have planned, and with everything basically already funded: Both tracks, both Big Rock (the 1.017-mile oval) and Little Rock (the facility’s short-track), will be ready to hold a daytime NASCAR race by the end of the year.”

It’s true some of this renovation money has come from the state of North Carolina. More is on the way, too. In November 2021, the North Carolina state budget earmarked about $50 million dollars to go toward renovating its three speedways — Charlotte, North Wilkesboro and Rockingham — made available via North Carolina’s cut of a federal post-pandemic stimulus package that passed in February 2021. Rockingham was announced to receive about $9 million of that sum and has received approximately $3 million of it to date, Lovenheim said.

It’s worth noting, too, that North Wilkesboro Speedway’s triumphant return to NASCAR only boosts Rockingham’s prospects of returning. That speedway was in worse shape in the winter of 2019 than Rockingham was — but thanks to the advocacy of Dale Earnhardt Jr. and the belief of Speedway Motorsports CEO Marcus Smith, the place had grassroots racing events on it in 2022 and held a Cup Series event earlier this month.

The event was well-received and well-attended. And it demonstrated that there was a thirst among NASCAR fans to find the old in the new, that there was value in reviving old grounds and strumming their prime strings of nostalgia.

There’s also something else compelling about places like North Wilkesboro and Rockingham.

“The interesting thing now in the financial model is — it used to be all about race day at the track, not TV,” said Charlie Perusse, the former budget director who oversaw the earmarking of federal post-pandemic funds to the state. He’s a longtime NASCAR fan with family connections to Richmond County, working closely with Lovenheim to make Rockingham’s return real.

“Now,” Perusse said, “it’s pretty much swapped.”

He has a point.

Part of the appeal of expansion in the early 2000s was to go to larger places and build larger structures and compel larger crowds. But priorities have since changed. Racetracks across the country have taken out or blocked off certain grandstands to make the fan experience more concentrated, more event-like, in the past decade: Daytona began removing its backstretch grandstands in 2015. Richmond did so in 2016. Auto Club Speedway in Fontana, California, slashed its grandstand seating by 26% in 2014, and even Charlotte and Atlanta and Dover (Delaware) made similar changes around the same time.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Perusse continued. “You make money off race day or you wouldn’t hold the race. But the real money is made in TV and less on the grandstands. And that’s why there is this movement to get back to the roots, because a lot of the TV is really interested in The Rock and in North Wilkesboro coming back.”

Outside of renovation, what else needs to happen?

Insinuating that Rockingham’s return to the Cup Series is imminent in any way, however, would be a bit misleading. Lovenheim has preached patience.

Ben Kennedy, NASCAR’s senior vice president of racing development and strategy, said that while Rockingham Speedway has “certainly hit our radar,” it is one of many racetracks across the country to do so.

“There are a handful of things that we think about as we look at these new tracks,” Kennedy said. “What does the market or demand look like? Is it something that’s important to the fans? Is it something that’s important to our other stakeholders in the industry — our teams, broadcast partners, kind of the rest of the broader group?

“And then, secondly and importantly, is the track feasible from a logistics perspective and a competition perspective.”

Kennedy acknowledged the triumph that was North Wilkesboro and the appeal it brought by being able to feel like the past and the present all at once. He said Rockingham’s renovation goals are similar.

But he reiterated that evaluating racetracks and formulating Cup schedules is a thorough, holistic, time-consuming process. The sanctioning body typically releases its season schedules in September.

“We talk to the team out at Rockingham, I would say, on a regular basis,” Kennedy said. “But we do that with a number of potential venues that we’re looking at. ... It’s always good to have a pulse on new and existing tracks, what’s going on in that marketplace, how management is thinking about the future of those facilities, if they’re putting improvements into it, if they plan to bring additional content to it.

“All of that is really important information for us as we think about making these decisions.”

Drivers, decision-makers, influencers support Rockingham’s return

One thing is clear, though: Decision makers and industry leaders don’t mind the thought of returning to Rockingham, even if they don’t exactly know how it would work out.

The governor, for one.

“There are a lot of similarities between The Rock and here,” Gov. Roy Cooper told reporters during All-Star Race weekend at North Wilkesboro in mid-May. “There is a lot of community. There are a lot of people who really want it to come back. And we know The Rock’s renovation is going to be successful, and I think we’re going to see a ton of events there. As to whether we get NASCAR back there or not, I don’t know. But I’m all for it, and I’m willing to step up and do what we need to do.”

Richard Childress, the former Cup driver and big-time race team owner of Richard Childress Racing, agreed with Cooper’s sentiment about Rockingham’s return. He remembers it for being a “driver’s racetrack” — one with a short-track feel with high-speed tendencies.

“The old track would wear out on you, and you’d wear the tires out really quick like Darlington, and it was just a fun place to go,” he said. “It would be nice to see a race back there, even if it would be just one every 10 years or something. Bringing back a little bit of history doesn’t hurt.”

So agrees Chase Elliott.

“I’d be for it,” said Elliott, the sport’s most popular driver five years running who has run at The Rock a handful of times, in a late model and even a truck when the Truck Series made a standalone visit there in 2013. “I thought Rockingham was a great racetrack. I loved racing there, especially at the time. ... It was really wide. Guys ran all over that racetrack, at least when we were running there. I think that would be another great fit.”

Rockingham Speedway also means a lot to Tony Stewart, the Hall of Fame driver who competed at the N.C. venue while he was running in the Busch Series (now called the Xfinity Series).

He’d love to see it come back, he said. But as the part-owner of a team and the owner of another racetrack in Eldora Speedway, Stewart also knows this: It might be an uphill climb.

“Anytime you try to add a venue,” Stewart told The Observer, “you’re taking something away from somebody.”

Of the 26 tracks on the 2023 NASCAR Cup Series schedule, only six are not owned by Speedway Motorsports — the race company giant founded by the late Bruton Smith — or NASCAR itself. SMI and NASCAR work side-by-side to sustain and balance the sport. (This is part of what made North Wilkesboro the site of the All-Star Race so painless; North Wilkesboro is owned by Speedway Motorsports.)

But this same fact is also what makes it difficult for owners outside the two companies to get a Cup date, Stewart said.

“I mean, I begged for a dirt race at Eldora, and we got a Truck race, and we proved that we could make it successful and went through all the growing pains of it,” Stewart said of the New Weston, Ohio, track. “And then we gave a dirt race to Bristol instead.”

All this considered, if you explain any shred of doubt, Lovenheim will level with you.

“If this were anywhere but here, I would 100% agree with you,” Lovenheim said. But then he’d argue that in a larger sense, recharging the sport’s fanbase in North Carolina is essential to the well-being of NASCAR — he’d bring up the golden triangle again.

“It’s right in the middle of where moonshine racing began,” he’d continue. “I mean, this literally started off as moonshine racers trying to outrun each other. And this is where they’re trying to bring it back as a centralization.

“You’re talking about L.A., you’re talking about Chicago, etc., etc. But this is bringing racing back to its roots.”

What else Dan Lovenheim sees

After that aforementioned ride on the freshly paved Rockingham Speedway asphalt, Lovenheim steered his Lamborghini off the oval, shifted it into terrain mode, cut it through the facility’s road course and parked it just outside of the venue’s short track.

There’s a cliff not far away, just beyond Turns 3 and 4 of the short-track. He walked over to it, right up to its edge.

Most would see a vista of trees and a water tower and small homes on that cliff. But Lovenheim saw Coachella — the music and arts festival in Southern California’s desert — when he saw the hundreds of acres with no noise ordinance. He saw Colorado’s Red Rock Amphitheater and visions of other iconic venues across the country.

He saw possibility, in other words. And for him, that’s always been enough.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports