Nazi diaries, forgers at the Vatican: How Delaware became a hotbed for solving art crime

The crime sounded like the plot to a movie.

At the secure private library of the Vatican, home to countless ancient treasures, a forger was afoot. The same was true in the centuries-old Riccardiana Library in Florence, at the National Library of Catalonia in Barcelona, at the Marciana National Library in Venice.

In daring burglaries dating back to at least the 1980s, a sophisticated thief had lifted priceless 15th-century bound editions of letters Christopher Columbus had sent from the New World, and replaced them with clever fakes — forgeries left undiscovered for decades, and left on display for the world to believe in.

The mystery turned out to involve an antiquarian with an extraordinary memory, a South American art collector, and telltale clues offered by centuries-old bookbindings.

But unlike in the movies, those rare monuments to history weren’t chased down by some suave but unorthodox Interpol agent with a cultivated mustache, or a reckless archaeologist with a yen for conspiracy theories.

The mystery was solved, instead, in Delaware.

Specifically, it was solved out of a little suite on the ground floor of a poured-concrete Wilmington office tower, originally designed for an insurance company.

Wilmington, Delaware, is hardly a glamorous nerve center for the international art scene, even as many great works do come there to be sheltered from taxes in anonymous warehouses. But when it comes to solving transnational art crime, Delaware is known to agents all over the country and, in some cases, the world.

In the past decade or so the small Wilmington office of Homeland Security Investigations, home base for fewer than 10 agents, has helped repatriate ancient historical artifacts to countries from South America to the cultural centers of the Old World.

The diaries of a Nazi collaborator. Religious paintings from old Cuzco in Peru. Roman manuscripts dating back to the 9th century. And of course those priceless letters from Columbus — which, technically, did have a price, going for around a million dollars.

Just last month, the island nation of Cyprus declared itself grateful for the return of two coins dating back millennia. Courtesy, also, of agents in Wilmington and Philadelphia.

What these cases have in common is a soft-spoken special agent named Mark Olexa who sports dark suits, tightly cropped brown hair and a look of visible discomfort when receiving praise. He receives praise reasonably often.

While international hubs such as New York and Washington remain busier sites for artifact smuggling and prosecutions, Wilmington pulls far above its weight. Olexa is one of few special agents who has made a perhaps unintentional specialty out of finding the long-lost and the irreplaceable pieces of the ancient world — and helping send them home.

And so when federal agents and U.S. attorneys from Philadelphia or San Antonio come across purloined Peruvian artifacts or a mislaid Roman coin, Olexa is often the person they call.

"Success breeds more success," said Kenneth Krauss, Wilmington's resident agent in charge. And more success breeds even more.

When asked about the reasons for that success, Olexa points to a long line of U.S. attorneys in Delaware and Philadelphia who’ve been diligent in doing the intricate research and legal wrangling required to close a cultural artifact case — often unique challenges that involve sealed warrants, wealthy collectors who stay forever anonymous and archaeological forensics.

He credits also the agents at other offices who bring in cases, and a parent office in Philadelphia willing to offer its resources for quixotic quests that might send agents to Florentine libraries or the home of a cagey Buffalo book collector.

But when you ask the head of the Wilmington office, he instead points to Mark Olexa.

"The main reason why we have such success is sitting right here next to me," said Kraiss, the agent in charge. "It's agent Olexa. We always say, it's all about our people, all about the agents and how they work. And it's a testament to Mark, why Delaware is so successful."

How the forged million-dollar Columbus letters landed in Wilmington

Art crime is far from where special agent Olexa started his career.

It’s also a small portion of the cases handled by HSI, the perhaps lesser-known wing of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The Philadelphia HSI office, which oversees Delaware, devotes the lion's share of its resources to tracing the movements of drugs and weapons, to human trafficking and to the many shadowy things that might happen on the internet.

In the mid-2000s, Olexa was part of an HSI team working to uncover arms procurement for Hezbollah in an investigation called Operation Phone Flash. He also worked on a case investigating six men who planned an armed assault on New Jersey’s Fort Dix beginning in 2006.

But in 2011 after coming to Wilmington, Olexa fielded a tip that seemed too strange to be real. A tip that would change the course of his law enforcement career.

A book dealer in Monmouth Beach, New Jersey, named Jay Dillon — whose resume includes selling the first book to visit the moon and an Egyptian Book of the Dead — had begun to notice something askew.

While surfing on his computer, Dillon saw a digital image of a bound 1493 letter from Christopher Columbus owned by the National Library of Catalonia, one of only 30 or so copies known to still exist.

Columbus' letter was among the world's first bestsellers, detailing his epochal landfall in a New World with “many islands inhabited by numerous people.” The residents did not resist, Columbus crowed, when he issued a proclamation and thus “took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King.”

But in that letter, Dillon saw something that unnerved him. He recognized the markings and imperfections on the Barcelona letter as the same ones he'd previously seen on a copy offered by a dealer — a feat of memory that boggles Paul Needham, a 15th-century book expert and former Princeton University librarian who consulted on the case.

“I’m still amazed that he spotted this,” Needham said. “He matched them up, from photographs in a dealer’s catalog. The probability would be infinitesimal that two copies would have tiny dirt spots on the leaves in exactly the same places between different copies. It was a brilliant discovery.”

Suspicious of forgeries, Dillon traveled to Barcelona and to other European libraries to examine their bound copies of Columbus letters. And then he walked those suspicions to the desk of special agent Mark Olexa.

Someone has been stealing Christopher Columbus letters and leaving reproduced forgeries in their place, he told Olexa. He arrived with troves of corroborating evidence.

“I just remember filling up a notebook with all this information that was being conveyed, and it was a bit overwhelming,” Olexa said now. “Prior to that, I didn't even know what a Columbus letter was.”

That meeting was the beginning of an investigation that would span at leeast three continents, four countries and 13 years — a case that made Olexa’s reputation as an agent who would know what to do with stolen historical documents, and that kicked off a long run of cultural artifacts recovered by Delaware's HSI office.

Here’s some of the more significant cultural artifacts retrieved with the help of HSI Delaware in the past decade.

2011-today: four letters from Christopher Columbus

After Dillon’s visit, and an improbable-seeming theory, agent Olexa went to Princeton to ask Needham, a world-renowned expert, for a second opinion.

He was gobsmacked to find that Needham backed up Dillon’s suspicions, and his research.

“At that point, trust and verify,” Olexa said.

So Olexa asked Needham to join him on a trip to the European libraries to analyze the purported forgeries.

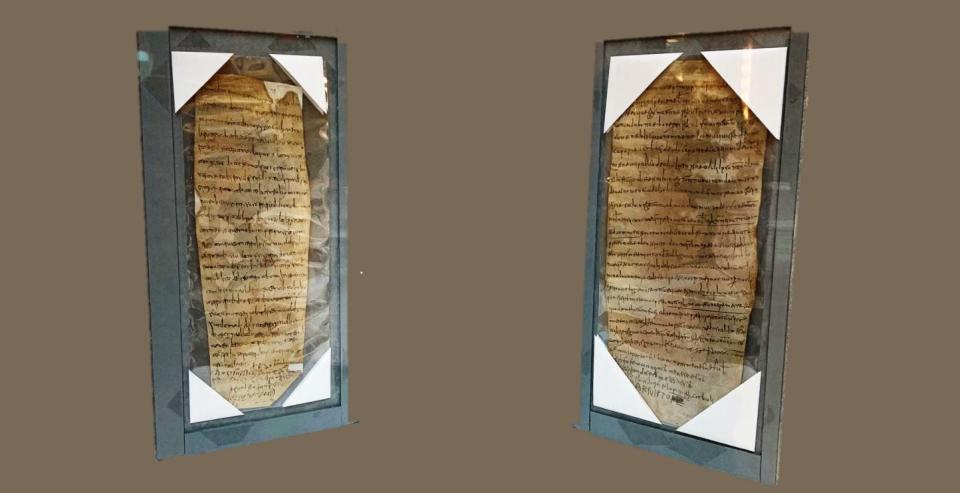

Librarians at the old libraries were reluctant to believe such thefts were possible — certainly not on their watch! — but the pages in the European collections were indeed reproduced forgeries, sewn back into the original book bindings.

“Once we start piecing together that these are forgeries in these libraries, well... where did the originals potentially go?” Olexa said.

The world of rare book collectors is small. It is “complicated and pretty secretive,” Needham said. But it is also a world that keeps quite detailed records, to verify the provenance of each rare book.

Using the little markings and imperfections on each Columbus letter as their guide — and also the way in which each page was bound — Olexa and Needham were able to track each of the pilfered originals and verify their source.

The book from Barcelona had ended up in the hands of a South American collector. The one from the Vatican turned up in Atlanta. And the Florentine letter? It had been given as a gift to the U.S. Library of Congress.

A fourth pilfered letter, from the Venice library, turned up in Texas.

The whole process, from the initial search to the legal process, took years for each stolen letter. But eventually each owner, including the Library of Congress, was persuaded that it was in their best interests to hand over the stolen pieces of history.

Three of the four have already been repatriated. Asked whether the pope was aware of the theft and recovery of the Vatican's letter, the library’s vice prefect concurred.

“Yes, he was informed,” Ambrogio Piazzoni told CBS news show "60 Minutes" in 2020. “He was very pleased with this return.”

The fourth Columbus letter, due in Venice, was scheduled to be sent home in spring 2020. But fate, and a worldwide pandemic, intervened. The historic letter still awaits its homecoming.

“We expect that to happen in the near term,” Olexa said.

2013: Finding the stolen diaries of Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg

By November 2012, the Wilmington HSI office had made substantial progress in the Columbus letter case.

“Once you have a reputation that you’re capable of bringing together a complex case like that, it has a snowball effect,” Olexa said. Referrals begin to come in — including some cases he can’t talk about yet, he said.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum contacted the Wilmington office about another stolen document: This one was the personal diaries of a Nazi intellectual named Alfred Rosenberg, whose musings were thought to detail Hitler’s early plans to “dominate” the Soviet Union.

The museum already hired a private investigator to track down the diaries, which had long ago been "improperly" taken from U.S. possession by a prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials, who'd since died in Pennsylvania. The museum's investigator had suspicions that a person in the Buffalo area now had possession. But suspicions aren’t proof. And the museum had hit a dead end. Could the Wilmington office, and the Delaware U.S. attorney, offer some help?

As it turned out, all that was needed was a little persuasion.

“(We) made a point of going out and conducting a very important interview with the person that was suspected of last having possession… I think he was made aware of the potential consequences, the legal implications and consequences, for him to possess property that belonged to the U.S. government,” Olexa said. This is not a legal burden you want to pass on to your children, Olexa told the person, whose name has not been released. The agents then left, not knowing whether the conversation had been successful.

But a month or so later, after consulting some lawyers, that person contacted HSI saying they might be able to get hold of that Rosenberg diary the government seemed to be looking for. On June 13, 2013, the diary was entered into the collection of the Holocaust Museum, where it remains.

“Having material that documents the actions of both perpetrators and victims is crucial to helping scholars understand how and why the Holocaust happened," said museum director Sara J. Bloomfield at the time. "The story of this diary demonstrates how much material remains to be collected.”

2012-2014: Stolen Peruvian paintings and cultural artifacts

In 2012, the Delaware U.S. Attorney’s office, and HSI Wilmington, recovered multiple Peruvian artifacts, in particular a millennium-old jar and a pre-Columbian bronze blade, an investigation that began and ended in Delaware.

But the more interesting story, said Olexa, is how four Cuzco paintings also found their way back to Peru.

Olexa had been invited to a training seminar on the subject of cultural repatriation. While there, he was approached by a HSI agent from San Antonio.

After a tip in 2009, agents from the parent HSI Austin office investigated and eventually located what they believed to be four Colonial-era devotional paintings stolen from Peruvian churches, painted in the Cuzco style thought to be the first European-influenced school of painting to flourish in the Western Hemisphere.

But the Texas agents had run aground on the last crucial step of the legal process: obtaining a seizure warrant to get the objects into the government’s possession. So they enlisted Olexa to help bring it home; Assistant U.S. Attorney David Hall was able to issue a seizure warrant out of Delaware after analysis by a subject matter expert.

“I was the one that ended up swearing out the seizure warrant,” Olexa said. “But ultimately (the case) was Austin's. It was theirs, they were the lead. I think it goes to show you that there's really no egos in this. You just get the job done.”

The four paintings were returned to Peru in a pair of ceremonies, in 2012 and then in 2014.

2019: Return of 9th-century Roman manuscripts and “Contorniato” coin

In 2019, another batch of ancient artifacts returned to Italy. These cases originated in Philadelphia, Olexa said, but the Delaware office was again brought in on the case because of Wilmington office’s ever-growing history with investigating cultural artifacts.

Two 9th century manuscripts from Benevento, Italy, detailing the sale of lands and vineyards, had been given to the University of Pennsylvania as a gift in 2010. Meanwhile, a nearly two-millennium-old Roman “Contorniato di Traiano” coin came into the possession of a Pennsylvania auction house upon the death of its previous possessor.

Both of these turned out to have been stolen from museums in Italy. In both cases, the owners surrendered the objects willingly after a long investigation.

2023: Repatriation of 4th century B.C. Cypriot coins

The Republic of Cyprus, a small nation near Turkey, sent a tip to the Philadelphia HSI office in late 2016, Olexa said. Two 4th century B.C. Cypriot coins had just been smuggled to the United States: one depicting Hercules, one with lions on each side.

But though the initial information arrived quickly, Olexa said, the investigation was both lengthy and complex — eventually comprising nearly seven years and involving the forensics team at the Smithsonian Institute. The coins finally arrived home, along with several other repatriated antiquities, in April of this year.

“We got the tip in ‘16, and the repatriation happened in 2023," Olexa said. “We will go to great lengths. Because if the roles were reversed, and we were asking them for something, we would hope they would take the same amount of time, effort and diligence.”

Other cases worked by the Delaware office during the same period include a kris dagger once owned by Oliver Hazard Perry, repatriated to the U.S. Naval academy Museum in 2019 from Canada; ancient feline ceramics from Costa Rica repatriated in 2022; and multiple other cases involving rare books.

The repatriation ceremonies for those books have yet to occur, Olexa said, and so he can't yet comment. But those cases, like many others, came in because of his previous investigation of the Columbus letters, he said.

"Once you start finding these things," said Olexa, "other things kind of find their way to you as well."

Matthew Korfhage is a Philadelphia-based reporter for USA TODAY Network.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Nazi diaries, Columbus letters: Delaware known for solving art crimes

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports