As MLB recognizes Negro League stats, let’s remember Black baseball in Fort Worth

Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

What was once known as “Negro baseball,” is now part of the Major League Baseball (MLB) record books.

There is a misconception that it started with the formation of the Negro National League in 1920 because that is when official record-keeping started. But Black baseball goes back to the late 1800s, and it thrived right here in Fort Worth.

I wrote an earlier column on the remarkable career of Rube Foster, known as the “Father of Negro Baseball,” who played two seasons in Fort Worth (1901-02) before hitting the big time up north. Foster was a pitching sensation, but he was a relative latecomer in Fort Worth. Black baseball had been played in the Lone Star State as early as the 1880s.

In 1888, team owners organized a “Colored Base-ball League” with Fort Worth, Dallas and Austin being the principal teams. The Fort Worth team took the name “Light Weights” for some inexplicable reason. The only qualification for a club to join was having an owner with deep pockets.

All the owners were “sporting men” (gamblers) like Fort Worth’s George Best, who could afford the costs of fielding a team. Teams changed ownership and turned over rosters regularly as owners’ personal fortunes went up and down. The Light Weights played their home games at Texas & Pacific ballpark when white teams were not using the field.

The Light Weights may not have had a fear-inducing name, but they had a fear-inducing ace pitcher named Frank Itson. Born in Denton County, probably in 1871 (some records say 1879), his family moved to Fort Worth by 1880. He was tearing up the league by 1891 as a “crack pitcher.” It was said batters couldn’t touch his “curve balls and shoots.” He played three seasons in Fort Worth (1891-93) before other teams stole him away, first Galveston, later St. Louis.

The teams did not play a pre-set schedule. Instead, games were set up when one team issued a challenge to another, sometimes doing so in the newspaper to bring out a crowd.

The best team in the league for several years was the Galveston Flyaways, who won the unofficial title in 1893. As champs, they received challenges from all over the Southwest, accepting as many as they could fit on the calendar. Every game meant a payday, and owners could pad the bottom line by placing side bets with rival owners.

The season ran roughly from April through September. Teams traveled by train and later by automobile or bus. Once in town, they played multiple games before heading home. Clubs fielded a traveling team of 12 to 14 players, all of them under contract, which didn’t benefit the player so much as it allowed owners to sell players at will.

A really good player like Frank Itson might be paid a decent salary just to play ball as long as the team was winning. Most, however, had regular jobs, too.

Coverage in the white-owned daily newspapers depended on how successful the town’s team was.

The first Colored Baseball League in Texas died of insolvency after less than a decade. A couple of Galveston entrepreneurs in 1897 organized a second league whose six founding members did not include a Fort Worth team, probably because one of the requirements was that clubs own their own ballparks. The Fort Worth team would not have a home ballpark until 1909, when Hiram McGar built McGar Park on North Main. Before that, they played in Douglass Park, also on North Main, moving there from Texas & Pacific ballpark on East Lancaster.

Successful teams drew both Black and white crowds. The difference was white fans sat in a reserved section of the bleachers.

McGar’s Wonders

McGar was the first owner of a Fort Worth team to promote it and exhibit any entrepreneurial skills. He was a successful saloon keeper and power broker in the Republican political machine when he bought the team in 1907. He changed the team’s name to the Wonders, a common name for both Black and white ball clubs. The Fort Worth team was sometimes called “McGar’s Wonders.”

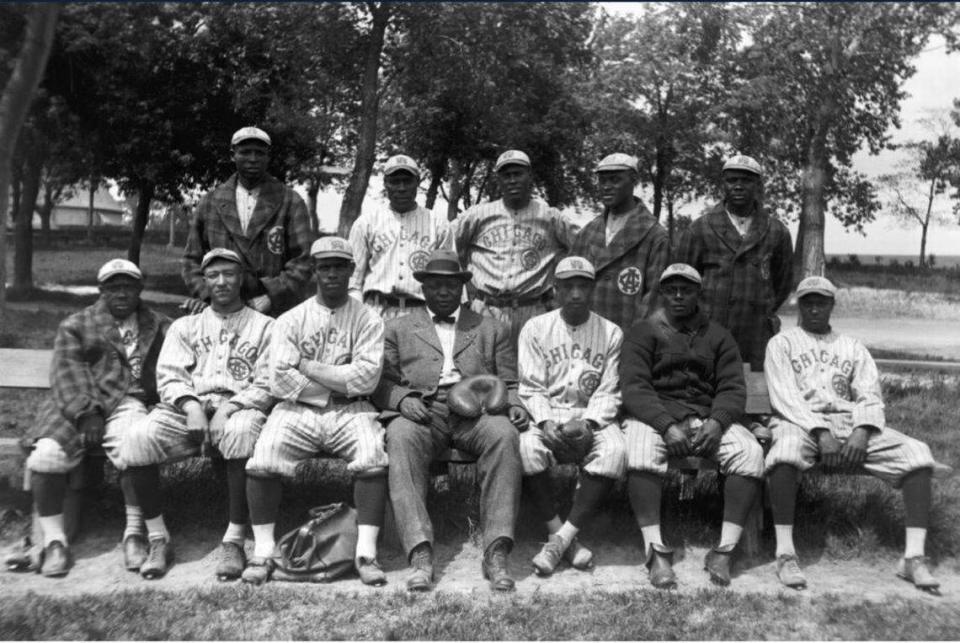

The team continued the winning ways it had enjoyed when Rube Foster was pitching in 1901-02. The team played 60 or more games a season as part of the Southern Circuit, which extended into Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana. In 1907, the Wonders won 48 games, which was good enough to win the championship “of the state if not the entire South,” according to the Fort Worth Record and Register. The whole city was proud. For the first time in Fort Worth history, a white newspaper printed the photograph of a Black team. The Wonders repeated as champions the following year.

In 1909, McGar moved his team to its new field, four blocks north of the Trinity River. For the first time, a Fort Worth Black team owned its own field, appropriately named for the man who got it built. The Colored Baseball League of Texas was still in operation, and McGar’s Wonders were admitted now that the team owned its own ballpark.

McGar was apparently a shrewd judge of on-field talent. Also on his teams were Louis Santop, described as “the first great African American homerun hitter,” and Willie Foster, Rube’s half-brother, both of whom went on to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The Wonders went unbeaten the first two months of the 1911 season. Their success led McGar to give them a new name in 1913, the Black Panthers. He was not trying to challenge the white minor league Fort Worth Panthers. Several seasons prior to this, the Telegram had offered this thinly veiled ridicule of the white team in comparison to McGar’s team: “Fort Worth has at least one ball team that can win games.”

Like successful modern team owners, McGar was not afraid to spend big bucks to acquire good players, buying out their contracts from other teams. He parlayed the success of his team on the field into the presidency of the Texas Colored Baseball League in 1916, which held its meetings in his Fort Worth offices.

The Black Panthers were champions again in 1920, winning the pennant on Sept. 16 by defeating the Dallas Black Giants. It was always satisfying to Fort Worth players and their fans when they beat Dallas. Fort Worth-Dallas games typically brought out more than a thousand people. The rivalry and the size of the gate were why they played each other several times a season.

What MLB now calls free agency was rife in the Black leagues, with teams basically renting a star player for a season or two. A star pitcher known as “Black Tank” Stewart came to Fort Worth in the middle of the 1920 season and played for a few seasons before moving on to the Dallas Black Giants. His departure coincided with the decline of the Black Panthers.

Tri-state league is formed

The Texas Colored League folded in 1928, replaced the following season by the Texas-Oklahoma-Louisiana Negro Baseball League. The old days of barnstorming teams playing catch-as-catch-can schedules was no longer an acceptable business model. The tri-state league fielded eight teams, including the Fort Worth Black Panthers and played a 100-game season from April through August. It tried to stir up interest by encouraging talk of a “world series” against the Negro National League champion, but it never happened.

By the end of the decade, the glory days of Black baseball in Fort Worth were over. Hiram McGar had given up ownership of the Black Panthers several years earlier, though he still lived in Fort Worth. The team, now called the Black Cats, was riding the coattails of the championship Fort Worth Cats white team.

No longer composed of veteran semi-pro players, ownership filled out the roster with college players on summer break. The Black Cats no longer had their own field and played their games at Panther Park (later LaGrave Field) when the white team was away or had a night off. And the Dallas Black Giants were now the team to beat. In 1929, the Oklahoma City Black Dispatch newspaper called Dallas “the best baseball city in the South.”

The tri-state league folded after the 1932 season, leaving recreation league teams as the only Black baseball still being played in Fort Worth.

Hiram McGar’s own fate is as sad as his team’s. By 1930, he was bankrupt and being sued for “debt and foreclosure.” Three weeks after the suit was filed, he died, on Dec. 13, 1930, just four days after Rube Foster died. McGar’s wife Agnes lived quietly in Fort Worth for another 28 years. The plaintiff dropped the suit against her husband in 1934.

McGar’s Park, where the Wonders and Black Panthers had played for 10 years, was also history, becoming a motorcycle racetrack in 1919.

In a few years, only old-timers could remember the glory days of Black baseball in Fort Worth. Now, with MLB recognizing the records of those players, we can finally acknowledge their historic contribution to America’s game.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports