When medical examiner investigations are delayed in NC, so is justice

In North Carolina, lengthy delays in completing medical examiner investigations don’t only torment families. They can leave criminals free from prosecution, for months, even for more than a year, prosecutors and police say.

Like many police across the state, law enforcement officers in Union County try to combat the opioid epidemic with the “death by distribution” law, a 2019 statute that allows prosecutors to file second-degree murder charges against dealers whose customers overdose on their drugs.

First, they need to obtain evidence that the illegal drugs killed someone. Because of the delays in state medical examiner investigations, it now routinely takes five or more months before that proof arrives.

That means that police and prosecutors must wait to file charges — and that potentially dangerous drug dealers remain on the street.

“It puts people’s lives in danger the longer we have to wait,” said Tony Underwood, chief deputy at the Union County Sheriff’s Office.

After 30-year-old Chase Drye was found dead in the front seat of a car in June 2020, Union County sheriff’s officers had to wait five months for the toxicology results that showed he died from a heroin overdose. Only then could they file a death by distribution charge against the suspected dealer – Cody Cummings, a 28-year-old Wadesboro man who has been charged with more than a dozen other drug crimes over the past five years.

Cummings was ultimately sentenced to a minimum of 18 months for involuntary manslaughter as part of a plea deal.

And in 2018, after a family member found 25-year-old Alexandria Gale dead on the kitchen floor, Monroe police officers had to wait six months for the toxicology results that proved that she, too, had died from a heroin overdose. As a result, the dealer suspected of providing the drugs – 38-year-old Jason Brickley – wasn’t charged with involuntary manslaughter until many months after Gale’s death. That case is still pending.

“If these people are still out, if we don’t have enough to arrest them, they’re not going to stop,” said Lt. Steve Morton, of the Monroe Police Department. “They’re making money.”

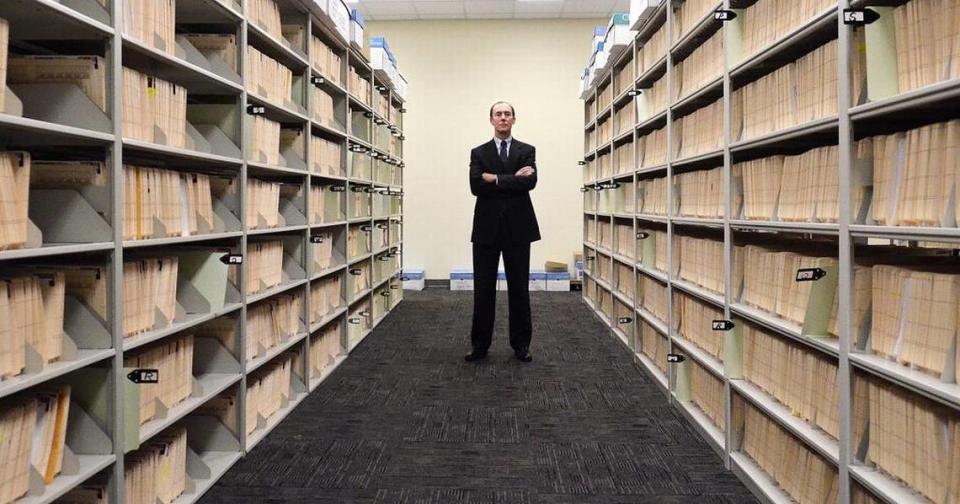

Stalled by state backlog

The Mecklenburg County Medical Examiner’s Office once handled autopsies for Union, Cabarrus and Anson counties, but is no longer doing so. Those counties now must rely on the backlogged state medical examiner’s office in Raleigh.

Union County officials hope that help is on the way. The Senate version of the state budget would allocate $20 million to build a regional autopsy center to serve Union and some surrounding counties. “We think it would speed things up significantly,” said Lt. James Maye, of the Union County Sheriff’s Office.

Gaston County District Attorney Travis Page also worries that the delays are leaving dangerous fentanyl dealers on the streets.

“When you’ve got cases that are not being charged because of delays, you have folks who you have reason to believe are criminals continuing to walk the streets of this community,” Page said.

Insufficient staffing at the state medical examiner’s office is to blame for many of the problems, Page said.

“The folks on the front lines on this — I believe they’re doing the best they can with the resources they have,” he said.

Babies at risk

The problem isn’t confined to drug dealers. Scott Reilly, the District Attorney for Catawba and Caldwell counties, said the medical examiner delays also can hold up criminal charges against people who kill infants.

Until autopsy reports are finished, he said, it’s often impossible to prove that a baby died from abuse — and, if so, when and by whose hands.

Consequently, Reilly’s prosecutors don’t file charges in such cases until the medical examiner’s investigation is completed.

But in the months while those investigations are pending, the suspects may flee — or, worse, hurt someone else, Reilly said.

“If they can take a child under a year old and shake it until it dies, I don’t want them walking around free,” he said.

‘Justice delayed’

As a result of the hold-ups in finishing autopsy reports, family members often have to wait for the “justice and closure they deserve,” Page says.

The logjam could also wind up harming people who are mistakenly charged with murder.

Mecklenburg County Public Defender Kevin Tully recalled a case from about 25 years ago when he represented a client charged with shooting a man to death in front of his house. The victim had been beaten by others before Tully’s client fired in his direction.

The client sat in jail for about 15 days before an autopsy disclosed that the victim had not been struck by any bullets, Tully said. He’d died from injuries suffered in the beating.

If that case had happened now, when autopsy reports routinely take five or more months to wrap up, the client likely would have been jailed a lot longer, Tully said.

Said Page: “There’s that old adage, justice delayed is justice denied.”

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports