Junior hockey's biggest fight isn't on the ice — it's in the courtroom

You could argue that even at the age of 10, growing up on opposite ends of the country, Lukas Walter and Spencer Abraham had almost identical stories.

Both boys lived for hockey and dreamed of one day playing in the NHL, but today, they are on opposite sides of a multi-million dollar class-action lawsuit that could change junior hockey forever.

The lawsuit alleges that since players typically spend between 40-60 hours a week with their teams, they make less than minimum wage. That, the suit says, means the three regional leagues that make up the Canadian Hockey League — the Ontario Hockey League, the Western Hockey League and the Quebec Major Junior Hockey league — are breaking provincial labour laws.

The suit, initially launched in 2014, is seeking $180 million in back wages, overtime and vacation pay.

Neither the WHL nor the QMJHL class action has been certified yet. A suit brought against the OHL was certified in April.

Walter is the representative plaintiff in the pending suits against the Quebec league and the WHL. Abraham has submitted a signed affidavit in support of the CHL.

Best junior league in the world

Abraham learned to skate on his family's backyard rink in Campbellville, Ont.

At the Walter household in Langley, B.C., Lukas listened to stories about his uncle Ryan who was the captain of the NHL's Washington Capitals in the early 1980s.

As teenagers they both made it to the CHL — the best junior league in the world.

Between 2011 and 2014, as Walter and Abraham suited up for hundreds of games in the CHL, their stories got farther apart.

In fact, their experiences in the CHL were so different that today they are on opposite sides of what has turned into a polarizing legal fight.

Welcome to the CHL

Walter admits that as a teenager he punched better than he skated.

"I must have been 14 or 15 years old my very first fight," he says remembering how he challenged a 17-year-old on the ice, while playing at in a summer league.

"I took my gloves off, I took my helmet off right in the middle of the rink," he says. "I got lucky with my second punch and he went down. Ever since then, I thought, 'I'm good at that.'"

Walter's willingness to use his fists turned heads. In 2011, at the age of 18, he found himself on a plane to Kennewick, Wash., to sign a contract with the WHL's Tri-City Americans.

"I didn't really look through it," Walter admits. "I was just really excited. I just go, 'No way I got this far,' so I signed it."

Across the country, Abraham, a smooth-skating defenceman, was making his debut with the OHL's Brampton Battalion.

Taken 289th overall, Abraham was one of the last players chosen in the 2009 OHL entry draft. He was the long shot who made the team just up the road from his family home.

His father, Gary, was with him when he signed his first contract.

"I remember my dad fighting off tears as he's driving home because obviously he knew how hard I'd worked and how badly I wanted this," Abraham says.

The kid from Campbellville and the boy from Langley were on top of the world.

After all, playing in the CHL is the most common route to the NHL. In 2016, almost half of the teenagers drafted by NHL teams came from the CHL.

Their paths diverge

"It's everything you dream of as a kid," says Abraham of playing in the OHL. "You get 7,000 people watching the game cheering and screaming. You're wearing colours and uniforms that you kind of always dreamed of wearing."

Abraham played 116 games for the Battalion before he was traded to the Erie Otters.

"You develop not only on the ice but the life skills is what you really take away from it," he says. "You learn how competitive the world is and that someone's always fighting to take your spot."

On the opposite end of the continent, even though Walter had made the Americans, he wasn't playing.

"I was out there one shift a game, sometimes zero shifts a game, on the bench just opening the door. And then maybe you get your one shift and you go fight," Walter says. "They didn't appreciate what I did."

Walter admits that things got so bad with the Americans that he thought about quitting hockey more than once. But while Walter was struggling, Abraham was playing in Erie with future NHL superstar Connor McDavid and getting closer to the dream of pro hockey.

It's all about the money

Even as their careers were going in opposite directions both Walter and Abraham were getting paid less than a dollar an hour.

That's pretty standard throughout the CHL, where players can make as little as $35 a week.

So when Walter got his first paycheque, he didn't understand how he could be making so little with so many fans at his games.

- CHL responds after Alberta judge orders teams to hand over

"I'm wondering how much money I'm going to get," Walter says. "They got a sell out — you know there's 11,000 people at that Spokane game against us ... and I go, 'Maybe I will get some money here.' ... [But I see the amount] and I kind of go, 'That seems weird.' It kind of shocked me at first."

What Walter was staring at was roughly $50 for two weeks with the Americans. He says he didn't complain at the time because he was a teenager chasing the NHL dream.

Now that Walter's career is over, he feels the CHL took advantage of him — that's why he's suing.

"We put in a lot of hours. It would be nice to see the boys making a little bit more money," he says.

Money has nothing to do with it

Abraham believes the money players make in the CHL is irrelevant.

"I was playing there for the opportunity to play in the best developmental league in the world," Abraham says. "My goal was ultimately to make it to the NHL, so I think that was enough incentive for me to play in the league."

Abraham worries that if the lawsuit is successful, some teams won't be able to pay minimum wage, and they'll go bankrupt. He says that would mean fewer opportunities for players to hone their skills in the league like he did.

The CHL argues much the same thing. They claim players are "amateur student athletes" and not employees, thus exempting them from minimum wage standards. In the past three years, B.C., Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan have all brought in legislation exempting major junior hockey teams from minimum wage and other labour laws.

This past winter, in response to a court order, the CHL produced financial records for all 20 OHL teams and 22 WHL teams. The records were analyzed by the accounting firm KPMG, which concluded that most teams either break even or lose money yearly.

However, a Toronto-based forensic accountant with Accountability Research Corp., Al Rosen, says the documents provided by the CHL teams are "grossly deficient."

"Clearly, some teams are doing well, and others not so well," says Rosen, who looked at the documents at the request of the media. "But with what was provided, it's impossible to know for sure if teams can pay their players or not."

Either way, Abraham insists he is proof that the CHL works.

He went from being drafted in the 15th round of the OHL draft to getting a tryout last fall with the NHL's Florida Panthers.

Lawsuit as inspiration

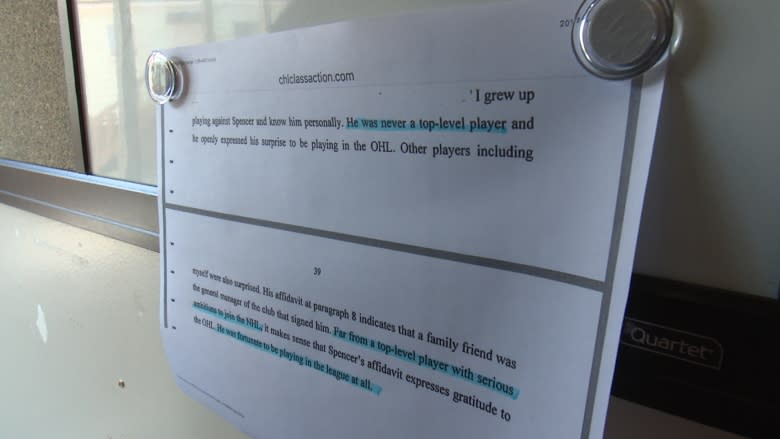

Abraham feels so strongly about his experience that he signed an affidavit in support of the CHL. In response, another former OHL player, Jeremy Gottzman, submitted his own affidavit attacking Abraham personally.

"I grew up playing Spencer, and I knew him personally," Gottzman's affidavit reads in part. "He was never a top-level player, and he openly expressed his surprise at playing in the OHL."

Abraham printed the comments — available online — and pinned them to a bulletin board beside his bed.

"It's just kind of motivation for me to keep getting better as a player and as a person," Abraham says.

One other thing Abraham has tacked on his bedroom wall is his acceptance letter to law school at Queen's University in Kingston, Ont. He starts his first semester in the fall, and his tuition is being paid for by the CHL.

Generally, players in the CHL earn one year of tuition and books for every season they play in the league. Teams also pay for all of the player's hockey equipment, travel costs, and the billet homes where they live during the season.

Hands that 'sound like crickets'

Walter couldn't decide where he wanted to go to school so his education package expired.

It's standard for the league to void educational packages 18 months after a player's overage season — usually once they turn 20.

Walter says he earned his schooling, and the league has no right to take it away.

"I think I'm fortunate with where I am today," he says. "Luckily, I got a great job with my dad and stuff, and it's going very well. I don't think junior hockey really set me up for a lot at all in life. I think I kind of did it on my own afterwards to be honest."

These days, Walter works with his father in their organic meat business and wakes up every morning with pain in his hands.

"They sound like crickets," he says as he makes a fist. "Too much hitting helmets right back when I was playing hockey."

Still, despite all he's been through, Walter says he'd do it all over again.

"I don't even know if I'll get anything out this," he says. "I just want the league to be better all around right. At the end of the day, I don't see the players [having] any say. You know, it's just you almost seem like a piece of meat sometimes."

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports