Jerry Krause, architect of six Chicago Bulls championships, dies at 77

Jerry Krause, the architect of six NBA title teams between 1991 and 1998, has passed away. The former Chicago Bulls general manager was 77.

[Follow Ball Don’t Lie on social media: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook | Tumblr]

A longtime baseball and basketball scout, Krause’s inroads within the Chicago scouting scene led to his ascension from that anonymous heap and into an NBA front office in 1985, with new Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf’s move to create a sense of symmetry between the Bulls and his other love, the Chicago White Sox. Shifting his focus entirely to basketball, Krause either drafted, hired or traded for Hall of Famers Scottie Pippen, Dennis Rodman and coach Phil Jackson alongside All-Stars Horace Grant, B.J. Armstrong, Metta World Peace and Elton Brand, and near-All-Star types Tyson Chandler, Jamal Crawford and Toni Kukoc.

The Chicago Tribune’s K.C. Johnson was the first to break the news:

Jerry Krause, GM of the Bulls for their six title teams, passed away this afternoon at age 77, a member of the family told the Tribune. RIP

— K.C. Johnson (@KCJHoop) March 21, 2017

[Sign up for Yahoo Fantasy Baseball: Get in the game and join a league today]

A Chicago native, Krause was born in 1939 to a decidedly unathletic family, yet this didn’t prevent him from becoming a high school baseball catcher of some renown at Chicago’s Taft High School. Upon graduation from Bradley University, Krause began to move up the professional scouting ranks and into a somewhat self-styled portrait of a secretive type with little to share unless the bosses were asking.

His secretive ways were hardly unique amongst baseball and basketball scouts at the time, but his lack of typical pro sporting airs and oftentimes brusque personality drove some to hand the “Sleuth” sobriquet to Krause’s call sheet. The moniker began as an unkind kiss-off before evolving into a semi-accurate portrayal of a man who loved his various jobs spent slumming around ballparks and basketball arenas, and loved the ability to seek out what he saw as moving and important and true.

Jerry Krause was not alone in his attempts to beat others to the scouting punch, and it was his move to push the then-Baltimore Bullets into drafting Earl Monroe No. 2 overall in the 1969 draft that helped establish Krause’s stature as a scout worth listening to. Krause, then just 30, selected Monroe out of historically black Winston Salem-State upon the recommendation of coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines.

Monroe would go on to a Hall of Fame career of his own, while Gaines’ son Clarence would later join Krause in the Chicago front office as the GM’s deputy, helping to spot and trade for the then-Ron Artest in the middle of the 1999 draft, among other accomplishments.

Krause was still working for the White Sox when Reinsdorf bought the Chicago Bulls in 1984, inheriting Rookie of the Year Michael Jordan along the way. Krause was hired by the Bulls soon after.

Jordan’s presence hardly did much to even out the rest of what Krause was handed with the Bulls. It was an uninspiring crew of not only limited basketball talents, but a drug-ridden, uninspired lot well aware of the fact that Chicago’s presence in the pro basketball scene was hardly legendary. With a series of failed franchises in the city and little to show for nearly two decades in the league at that point, Chicago was an NBA also-ran. If that.

Michael Jordan, you may have heard, changed a bit of this, but MJ wouldn’t have had a team to stand on, shout at, or pass to were it not for the brilliance of Jerry Krause.

Even after less than a year running the team, Krause became more than aware of Jordan’s propensity as a rookie to tear down those whose competitive tastes didn’t suit him. Though the new Bulls GM could hardly touch the basketball net without a boost, he related to Jordan in this cutthroat realm, and while his initial work may have driven the Olympian and near-league-leading scorer nuts, even MJ could see the point here.

Drug offenders were out, as were high-usage players who needed to dominate the ball in order to score. It was a sharp demarcation point involving personalities that were not to be seen anywhere near Michael Jordan, both on-court and off. Jordan helped himself with his dogged sense of sporting spirit (he was hardly a Rush Street regular) and Krause quickly spoke to his new player’s thirst for the jugular by drafting Charles Oakley in 1985 with the first lottery pick of the Krause Era.

Oakley, a 22-year-old Virginia Union product, informed the limited batch of local media sent out to meet the draftee upon his Chicago debut that Jordan would not have to lead the Bulls in rebounding in his second year, as he did in his rookie season. Oakley, Krause, and Jordan, however, could not have expected the eventual setback that permanently altered MJ’s view of his new, technical, boss.

Just two games into 1985-86, Jordan broke a bone in his right foot. A potential career-ending injury then as it is now, the 23-year-old colt fought vigorously to not only return to the Bulls ahead of schedule, but to play on his own in pickup games in his home state of North Carolina during the rehabilitation process. Krause and team owner Reinsdorf, freaked out beyond recognition at the idea of the NBA’s next great star falling victim to the same series of bone breaks that stopped Bill Walton’s career in its tracks, were borderline horrified.

The team’s medical staff and front office went out of their way to convince Jordan to take the slow road back, once pointing out (to Jordan’s great unease) that he had a one-in-10 chance of ending his career should he come back too early from the break and fall on the foot improperly. Jordan, not keen to be compared to either Walton or a piece of property, fought back at what he saw as needless Chicago paternalism, and the chance to add to better lottery chances with a 1986 playoff miss.

Krause wanted another high lottery pick to play with, but at the time tanking was anathema, and the Bulls clung to the playoff bracket in 1985-86 under Jerry’s first coaching hire, Stan Albeck. A late-season return from Jordan under a minutes allotment pushed the 32-win Bulls into the postseason and the NBA history books, as MJ set a league record with 63 points against the eventual-champion Boston Celtics.

It was another first-round loss, though. The second of Jordan’s career, this one coming after a first full season for Reinsdorf and Krause that, in a lot of ways, Krause and Jordan would never recover from. The 1986 draft did not help.

Smitten with his gifts as a proto-Kevin Garnett, Krause selected Ohio State 7-footer Brad Sellers with the No. 9 overall pick, sliding the big man into a small forward slot that would not be occupied by players of his skillset for decades. The problem for Krause and the Bulls was that Sellers was not the proper Patient Zero for this exercise, and Jordan would still be seen ribbing (to put it kindly) the selection on the Chicago team bus more than a decade later.

That relationship, as with many in Jordan’s life, was rarely documented with extended nuance or compassion, mostly because there was little coming from Jordan’s end. Michael Jordan bullied his boss, ceaselessly, for years. By the time it came to honor Jordan and, by extension, Krause in the form of Jordan’s 2010 Hall of Fame induction, Michael decided to use his stage and Krause’s absence to ridicule his former co-worker in a scene that was not only a low point in Jordan’s career, but one of the darker days in NBA history.

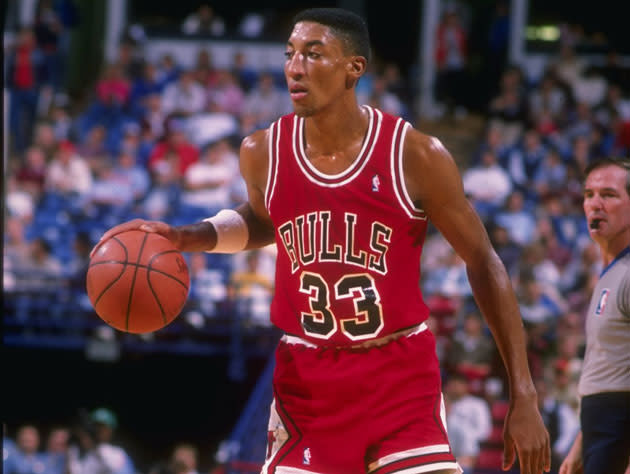

Krause rebounded by the setback by dealing one other 7-footer at the height of the NBA’s obsession with the center position for a lithe, 6-foot-7 rookie out of a second-tier college to which nobody (outside of Krause and, perhaps, the late Marty Blake) knew the directions. Scottie Pippen, in time, would become Krause’s greatest triumph as judge of raw talent, drive, and potential impact.

Pippen entered post-high school life as a 6-foot point guard with little prospects outside of his willingness to become a bit more than a small school point guard. The youngest of 12 siblings, Pippen’s obsession with finding a way out was deservedly blessed with a growth spurt that left the Central Arkansas product at 6-foot-7 by the end of his senior year, with Krause only needing the collusion of a series of NBA teams, owners, GMs, agents (including former Cubs shortstop Don Kessinger, now partially representing Pippen) and media in order to make Pippen a Bull.

This led to Krause’s move to deal Olden Polynice and a series of swapped and/or protected pick updates (that wouldn’t look out of place in 2017) to Seattle for Pippen in 1987, his signature move. It would take a few years – Central Arkansas, in one way, is a lot farther away from the NBA than Michael Jordan’s University of North Carolina campus is – but Pippen would eventually retire as the greatest sidekick in NBA history.

There would be better and more famed second-best players on championship teams, but no NBA player to date has performed the role of the decided deputy better than Pippen. His all-around gifts were not only perfectly suited for the Bulls, but also the emerging NBA. In Scottie Pippen, Krause found his ultimate “pup.”

That’s what he called the good ones. Fingertips counted, as did wingspan and neck size. Length and versatility mattered. Reputation, background and attitude also played a significant role in the research process – Krause didn’t leave behind all that those 1950s and 1960s scouts left him upon his move to the big city – but so did a significant series of other, often barely defined skills and traits that led to Krause growing more and more fond of potential future Bulls behind the scenes, telling nobody and everyone who would listen all at once. That’s what passion does to a professional.

Phil Jackson, once one of Krause’s pups from Phil’s playing days (the Bullets, with Krause as deputy GM, attempted to draft Jackson in 1967; Krause was taken by his wingspan and broad shoulders, along with Jackson’s box-score attributes), was by now the team’s head coach after a furtive, ahead-of-its-time (he would burn out after three years) dalliance with Doug Collins in his first head coaching job.

It was that triptych, with Pippen and Jackson alongside Jordan, that would drive the Bulls to a series of championships. The trio’s unhealthy and combative relationship with Krause, however, would not only lead to the demise of the Bulls franchise in 1998 in terms of pure NBA relevance, but also fissures in their own personal relationships that sadly, with Krause’s death, never healed.

Krause shared that competitive bent with both Jordan (who would cheat at board games with family members), Jackson (same) and Pippen (who could only return to the scene of the 1998 NBA Finals once back spasms were physically punched out of his back by a Bulls staffer in the visitor’s locker room, as Krause watched in semi-hiding). But it was the similarities in style and in interaction that would eventually lead to the unnecessary, if inevitable, end of the Bulls’ dynasty.

Not before Jerry Krause, still not a Basketball Hall of Famer, put together six championship teams.

Following Albeck’s winsome turn, Collins’ directive guidance was needed to the point at which Jackson would then hit the release valve. Jackson and Krause both swear that Phil’s developing love for the triangle offense was only part of the package when he was hired as Bulls coach in 1989, but it didn’t hurt Jackson’s chances that Collins dismissed the potential for assistant coach Tex Winter’s infamous offense, seen then as now as a gimmick, and that Jackson saw sparks from his old championship New York Knicks teams in the images culled from Winter’s words and descriptions.

Reinsdorf, a New York City native, saw the same thing, as the momentum was now in place. Krause stayed diligent in drafting Grant in the 1987 draft before shipping Oakley to New York in exchange for oft-injured center Bill Cartwright; for all of Krause’s modern-as-tomorrow angularity, he still adhered to the NBA credo that a B-level starting center will always be more impactful than an A-level power forward, even if that power forward (in Oakley) had just nearly led the NBA in rebounding.

Quentin Dailey turned into Kyle Macy, who turned into John Paxson. Orlando Woolridge and Jawann Oldham were asked to move on, while Sedale Threatt and his off-court habits were turned into the steadier Sam Vincent. Dave Corzine and Rory Sparrow were retained for guidance, as was Granville Waiters for the jokes.

The 1988 draft brought the much-maligned Will Perdue, an unfortunate punchline at reserve center who was in actuality phenomenal value as a low-lottery pick. The 1989 draft was a bit of a miss, as famed Oklahoma center Stacey King failed to put the Bulls over the top, but Krause recognized a needed corner 3-point shooter in B.J. Armstrong. The 1990 draft saw Krause stash the draft rights to the talents of the best international player in the game at that point, Yugoslavia’s Toni Kukoc.

The Croatian-born 6-foot-11 point guard would need a few years to come over, years that were happily filled with three NBA championships in Chicago between 1991 and 1993. Krause’s giddy, somewhat tipsy dance to the strains of “Go, Jer-ry” on his team’s flight home from a win over the Detroit Pistons in the 1991 Eastern Conference championship probably ranked as a career highlight for the scout, who would move on to his first title in the pro ranks a month later with Chicago’s 1991 Finals victory over the Los Angeles Lakers.

There was still work to do. Jordan, Pippen and Grant were all in their primes, Paxson and Cartwright a little older, but all needed their disparate contract wishes met on the fly. Kukoc needed convincing to come over, to the great unease of Jordan and especially Pippen, who had watched his “pup” status fade even as his NBA stardom grew. There was always another prospect to chase down.

Cartwright and King became Luc Longley and Bill Wennington, while Krause took a chance on dealing Perdue for Rodman and used his rare free-agent cap room on Ron Harper. Rodman came as advertised, a self-promoter who also ranked as the shyest person in the room, a flashy performance artist whose best work still came away from the stat sheet, a Pippen-esque “pup” of sorts who had no room being in the NBA in the first place, let alone piling up ring after ring.

All of it worked, even while Jordan spent a year and a half away from Bulls chasing his dream of becoming a professional baseball player on Reinsdorf’s White Sox.

There were missteps, yet those misses found a savior not in the form of Jordan, but in Krause’s insistence on building a team as he saw fit. The 1993-94 Bulls, built around Pippen, a rookie Kukoc and an All-Star in Grant who by this time was more interested in the contract he’d sign with his next team, still won 54 games and contended for a championship. Jerry Krause just put together winners, almost without reflex, and without any best-selling book titles to his name.

It got to Krause, and others.

Every summer brought a new round of boos for the man that Chicago fans — never much for tact, poise or reason, even at their rare championship moments — mercilessly decided to roast during the team’s post-victory title parades. If Krause wasn’t obsessed with building a champion that didn’t include Jordan, he didn’t show it, and by the time of what should have been Chicago’s peak through its second set of three-peat titles, the writing was on the wall.

Phil Jackson didn’t want to run the Bulls, but he wanted to be paid as if he did, and he wanted to negotiate with Jerry Reinsdorf directly when it came time for new contracts in 1996 and 1997. Partially because Jerry Krause needlessly had a rule against talking turkey in a room with coaches that came armed with agents (aren’t all of us supposed to negotiate with legal representatives?), but also because Krause and Jackson still worked under the cloud of a scout/player relationship that, even 30 years after Jackson’s personal player showcase for Krause back at the University of North Dakota, just could not die easily.

Pippen, desperate for stability in a life marked by anything but, signed a long-term deal in 1991 that the team warned him against committing to. By 1997-98, he was in a contract year and working as the NBA’s 122nd-highest paid player. Rodman rewarded Chicago’s good faith and $9 million deal for 1996-97 by kicking a cameraman the following season, all while Jordan made nearly the entirety of Chicago’s salary cap himself following a 1996 free agent turn that, once again, Krause was locked out of in favor of direct negotiations with the owner.

Working around the fringes – Krause helped turn former 20-point scorer Harper into a mini-Pippen, Steve Kerr was rescued from Orlando, the former Brian Williams found his lone, happy NBA home under Krause, and scads of Sleuth-located role players made millions and earned championship rings – didn’t appear to be enough. Krause had never built an NBA team from the ground up, and to the eyes of an outsider, it could have appeared as if Jerry was champing at the bit to try, even if it meant driving Michael Jordan to retirement.

Even if Jerry Krause never drove Michael Jordan to retirement. He can be credited, however, for his role with others in helping lord over the dismantling of the dynasty.

The 1997-98 season, with Jackson having confirmed that he wanted no part in coaching past that particular year prior to the campaign (a confirmation encouraged in no small part by his non-entity of a relationship with the GM who hired him), was dedicated as the Bulls’ last. Jordan was no fan of the unofficial decision to term the season a last waltz, but Pippen was keen to explore free agency, Jackson was eager for life as a well-heeled basketball martyr, and 36-year-old Rodman was on his last basketball legs.

Krause hardly helped himself. His “organizations win championships” credo from 1997’s Chicago media day has seen time and context heap kindness on the statement in retrospect, but it’s still a statement you never make on record. Especially in light of the public perception of the Sleuth as the ungrateful executive who never drafted Jordan in the first place, the guy that now wanted to take MJ and his battalion of basketball memories away from us for good.

The GM didn’t help himself by refusing to invite Jackson, among others, to his daughter’s 1997 wedding. It was a small slight on the surface, but one that stands out once it became apparent that then-Iowa State coach Tim Floyd was invited to the ceremony, alongside Bulls assistant (and Krause’s last coaching hire) Bill Cartwright. Jackson was livid at the snub, but smugly played it up to great effect. As did Jordan, knowing that his time with the Bulls was limited, and Pippen, during an infamous, drunken trade demand pitched during a team bus ride late in 1997.

Jerry Krause hadn’t exactly gone Nixon by this point, but it wasn’t a graceful exit.

The Bulls’ 1998 title would indeed be the team’s last (with Jordan, and perhaps in total), though Pippen’s painful back-spasm performance in that visitor’s locker room helped thaw the détente a bit between Pip and the admiring GM who had drafted him over a decade before.

Swayed by terrible press, and looking forward to the benefit of an NBA lockout and the knowledge that there was no way in hell these guys would taken them up on his offer, Reinsdorf held a 1998 press conference a month after the team’s final title, alongside an uneasy Krause and Floyd, to announce Floyd’s hiring as president of basketball operations. Krause was, technically, the VP to this made-up title at this point, while Reinsdorf encouraged Jackson, Pippen, Jordan and even Rodman to return for 1999 and beyond.

It was an embarrassing display that Reinsdorf mostly got away with, but it helped damage Krause’s credibility even further as he stood at the podium, attempting (along with his boss and hoped-for future coach in Floyd) to have it both ways. Jordan, Jackson and Pippen would not come back to Chicago with Jerry Krause at the helm as GM, and the NBA contract rules that stemmed from that 1998-99 lockout prevented Krause from putting together a team as he saw fit, with rules fashioned in a decade that was rapidly running out.

With maximum contracts now a part of NBA reality, Krause could no longer outbid for the services of Kobe Bryant, Ray Allen or others in his hopes to create another champion with Kukoc on board. Left bereft of options, Krause decided to tank 1999 and, eventually, years 1999-00, 2000-01 and 2001-02 as well. These aren’t jokes – NBA players were not only squeamish about taking over Jordan’s locker, but Pippen and Rodman’s, as well. As free agent after free agent declined Chicago’s money, the Bulls ran one rebuilding year into another.

Floyd was at the helm for most of this, though, so even the additions of Brand, Artest, Crawford, Chandler, Eddy Curry, Jay Williams, and signees Brad Miller and Brent Barry failed to take hold. By the end of 2002-03, with Krause in declining health and with a litany of his former pups (Miller, Artest, free0agent signee Ron Mercer) sent to the Pacers in exchange for the win-now stylings of the 30-year-old Jalen Rose, it was just about up.

Krause and the Bulls decided to end the partnership, with John Paxson moving from behind the broadcast microphone (after one year serving as Phil Jackson’s assistant, a travel-heavy role he reportedly disliked) into the front office as GM. The Bulls have gone to make the postseason in all but three seasons since 2003, but with a series of low-potential, low-ceiling transactions bent on securing that extra round of revenue for the team’s ownership group.

Though Krause no doubt respected Paxson, his former point guard, the team’s history in the years since Krause’s departure just hasn’t been as fun. The Bulls now deal in professionalism — when it suits them, at least — as opposed to passion.

It was that passion that Jerry Krause shared with his teammates – Michael Jordan, Phil Jackson, Scottie Pippen – that drove this thing. That made it so the 1990 Eastern Conference finals lost to Detroit felt like the end of everyone’s world. That made the defense of the championship, the ability to rank alongside dynasties from Boston and Los Angeles, so crucial. That made the return to the top in 1996, with 72 wins behind it, so satisfying. However briefly, because even the fullest belly will still see you seeking more, more, more.

Jerry Krause’s drive brought his hometown NBA titles. It pushed him to not only seek out prospects in odd places, names and burghs coming directly from central casting and the too-easy sportswriter’s playbook, but to challenge himself and others into admitting that the game itself can never truly be sussed out, that there’s never been a formula to this gig, and that there never will be.

That while there was no such thing as a correct answer in creating a championship team, talent and hard work would always give the spirit a fighting chance if the search for the next pup not only keeps you up at night, but also has you springing out of bed later the same morning. Giddy to let the world know that you saw that long-armed, guard-slash-forward first.

Krause would have been the first to tell you that the titles were his legacy, and that he hardly needed any of the plaudits that most others with his championship pedigree so dutifully enjoyed. Jerry didn’t ask for any of it, but he was cruelly denied basic human compassion from not only his co-workers and former friends, but by the Chicago and NBA community at large. The name “Michael Jordan” will be in the first paragraph of most of the obituaries you’ll read on the man, and while that is journalistically appropriate, it does little to advance Jerry Krause’s innovations forward.

Jerry Krause was a basketball giant who only lent his uncompromising approach to his work, and not his summation of the game itself. He gave the mistakes and triumphs equal sway as teachable moments, while guiding generations to come toward the belief that teams can be built with a sense of whimsy, with glee, with interest and with risk-taking, and with panache that, at times, seems ill-suited for the guy stuck off to the side of the bleachers. Wearing a long overcoat in July.

That’s a complicated life lived mostly without unnecessary regret or compromise, spent almost entirely working at a much-loved job that Krause both dignified with his presence, and deified with his words, reminders, and practice. We should all be so lucky to have lived a life like that. Like Jerry Krause, a scout and champion in equal measure.

– – – – – – –

Kelly Dwyer is an editor for Ball Don’t Lie on Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email him at KDonhoops@yahoo.com or follow him on Twitter!

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports