Janet Guthrie made history in 1976 World 600 in Charlotte. She also made some people mad

Janet Guthrie heard the chant from some of the Charlotte Motor Speedway fans when she walked onto the track for the first time, in May 1976.

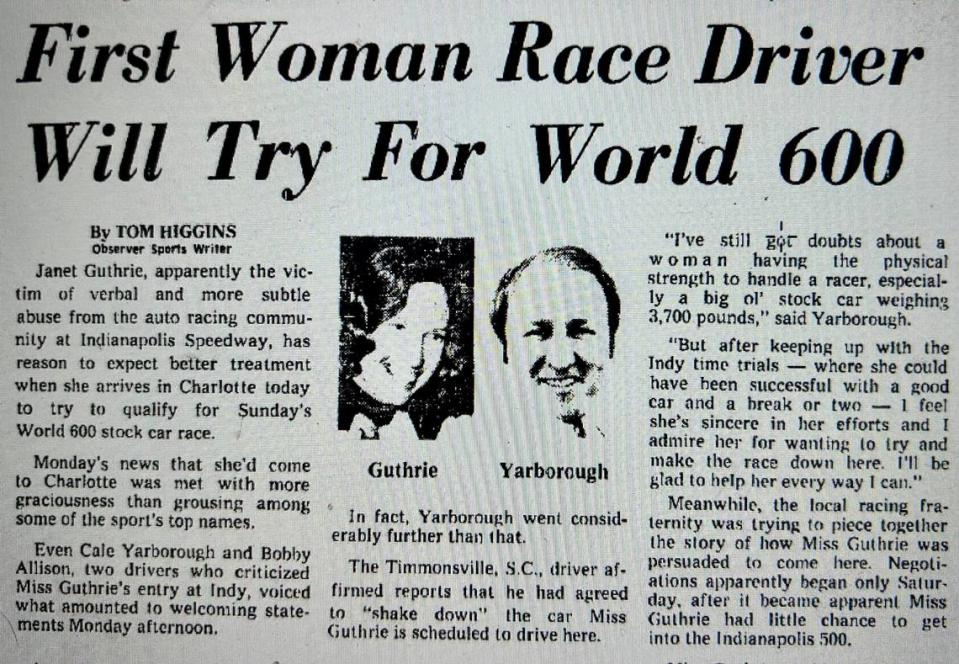

Following a last-minute flurry of unlikely events, Guthrie was poised to attempt to run the World 600 — the iconic race that was the longest on NASCAR’s top circuit. First, though, she would have to become the first woman to qualify for a superspeedway event in NASCAR’s premier series. It would be no sure thing, given that 60 drivers would be competing for only 40 spots.

Some fans wanted her to make the field and make history. Some were ambivalent but curious. And some absolutely didn’t want her in a NASCAR race.

As Guthrie remembers it now, at age 86, the repeating catcall was clear and slightly profane in its message.

“I can remember those calls floating over the grandstand,” she said in a phone interview from her home in Colorado. “They were saying: ‘Get the tits out of the pits! Get the tits out of the pits!’”

Guthrie, though, wasn’t going anywhere. The 600-mile race at Charlotte will be run for the 64th time Sunday, but that one in 1976?

That race remains one of the most memorable of the previous 63 in the race now called the Coca-Cola 600 and contested each Memorial Day weekend — not for who won (David Pearson) but who finished 15th (Guthrie, who was driving a stock car for the first time in her career).

Guthrie finished ahead of future Hall of Famers like Dale Earnhardt Sr. and Bill Elliott that day, and in the process made believers out of a sellout crowd of 103,000 that at the time was reported to be the largest number of fans to witness a sporting event in the Carolinas.

Humpy Wheeler, then the general manager at Charlotte Motor Speedway and now retired, was instrumental in getting Guthrie to Charlotte along with CMS track owner Bruton Smith. The two thought so much of Guthrie — and of the attendant publicity that her attempt to finish the race would bring — that they arranged and partly financed a car for her to drive, a well-known crew chief for her to lean on and a female team owner from Charlotte to help pay the bills.

“The reaction was generally good with the fans,” Wheeler said in a phone interview. “It was something else for them to see. Part of a good show. But the reaction was horrible with the drivers. Some of them were like: ‘Why didn’t you buy me a car when I was a rookie?’ Or worse.”

When Guthrie met Richard Petty, “The King” of stock-car racing, for the first time that week, she said she received an icy reception.

“I went to shake hands with Richard Petty and thought I’d get frostbite,” she said.

At the time, Reid Spencer was a journalist for The Charlotte Observer helping to cover the race. His assignment became to ask every male driver what they thought about Guthrie trying to make the field. As he would write many years later in a story for NASCAR’s website about the week: “Many of the responses I got would have blown up the sport had social media been active (in 1976). Some were misogynistic. Some were downright vulgar. Only about a third of the responses were fit to print in a family-friendly newspaper.”

Guthrie was ‘born adventurous’

Guthrie, who was 38 at the time, was no wet-behind-the-ears racing rookie. She had already had an accomplished career on and off the track and would eventually become the first female to compete both in the Indy 500 and the Daytona 500 (although both those races came later after her race in Charlotte).

A New Yorker, Guthrie was already an established sports car road racer by the time she had shown up in Charlotte. She also had flown planes since her teenage years. “I was born adventurous,” she said.

Guthrie also had a degree in physics from the University of Michigan and had worked as a research and development engineer. An IndyCar owner named Rolla Vollstedt offered her a spot in 1976, and she set a goal of qualifying for the 1976 Indianapolis 500 that May.

She missed, but not by much, and it came down to the last day of qualifying.

In the meantime, Wheeler and Smith had watched as Guthrie’s attempt to qualify for the Indy 500 dominated motorsports coverage and moved some pre-race stories about the World 600 inside the local sports sections. They didn’t like that and decided that Wheeler and his staff would make a major push to get Guthrie to Charlotte for the World 600 — run on the same day as the Indy 500 — if she didn’t qualify for Indy. Never mind the fact she had only seen a stock car once before and had never been inside one.

At first, Guthrie would barely take calls from Charlotte, so intent was she on making the field for the Indy 500. She didn’t want to consider a backup plan yet.

“You represent failure to me,” she told Wheeler.

“It’s not failure, though,” Wheeler insisted. “We just want you down here, and we’ll do anything we can to make that happen.”

Guthrie had some success at Indianapolis when A.J. Foyt — a legendary and legendarily irascible driver and owner in racing circles — allowed her to use one of his backup cars for some practice runs when Vollstedt’s car turned out not to be up to snuff.

“I brought that one up to speed right away and was fast enough to make the field in his car,” Guthrie said of Foyt’s backup car. “But in the end, he decided not to let me (drive the car for the actual race). So that was rather a crushing blow.”

Foyt, though, would quickly resurface again in the saga.

Guthrie didn’t want to sit around Indianapolis without a car to drive. Suddenly the trip down South seemed like a promising idea to her, if Wheeler and Smith (who died in 2022, at age 95) could work things out.

Wheeler, then, had to find a car, an owner and a crew chief for Guthrie, whose connections in NASCAR were more or less non-existent. He found the car by turning to one that Foyt had once driven and still had an ownership stake in — Foyt was so versatile he won big races on both circuits in his career.

“Dealing with A.J. Foyt was like eating barbed wire,” Wheeler said. “But money talked.”

Junior Johnson’s ‘magical hammer’

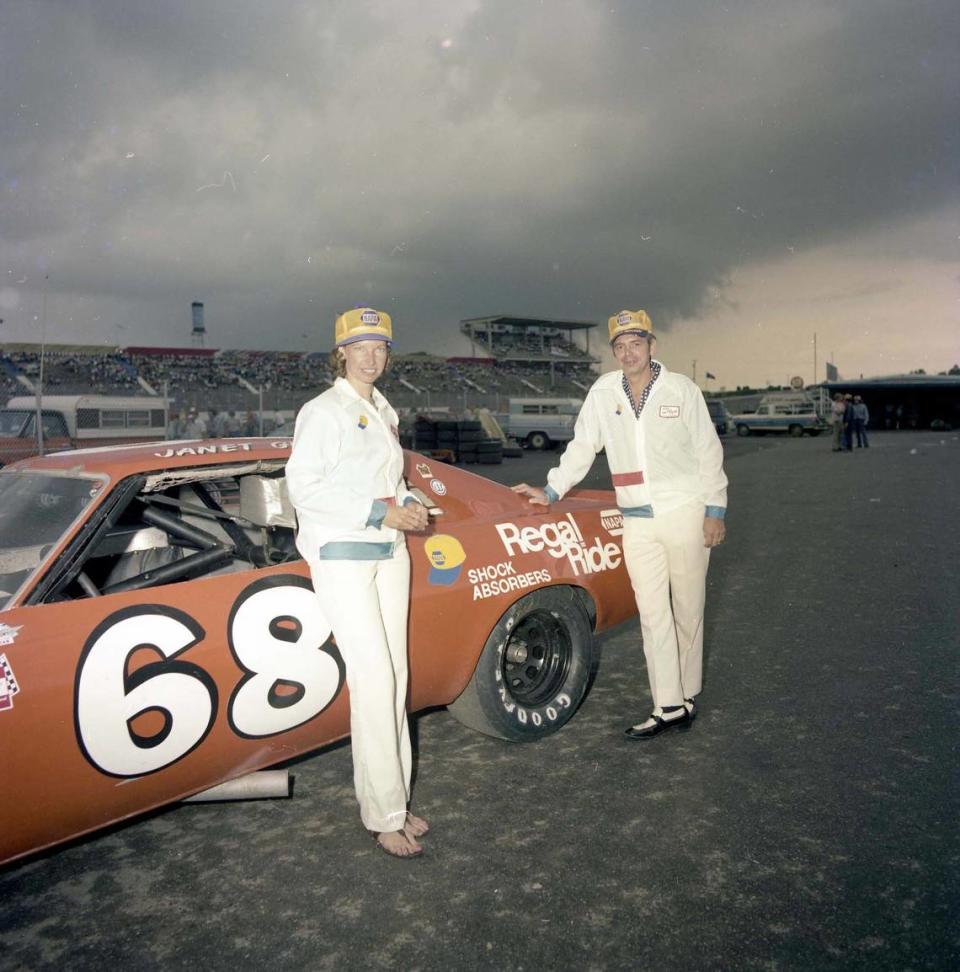

The crew chief would be Ralph Moody, well-known in NASCAR circles. And for the owner, Wheeler had an idea. What about a female owner for a female driver? He called up Lynda Ferreri, an executive at First Union Bank in Charlotte who had been around the sport.

“How would you like to become a car owner?” Wheeler asked.

Ferrari was all for it and, within hours, the deal for Guthrie was in place. Guthrie got to Charlotte early on race week, trailed by all manner of media.

“It was the first time I didn’t have to call a press conference,” said Wheeler, who was Charlotte Motor Speedway’s GM from 1975-2008. “The media just followed her and then we had one. It may have been the biggest press conference we ever had.”

Determined to prove herself, Guthrie tried to keep a relatively low profile and learn as much as she could about the heavier stock cars in a short amount of time so she could qualify.

One problem, though: The car Wheeler and Smith had arranged for her wasn’t very fast. Her first practice laps weren’t going to get her anywhere close to qualifying.

Vollstedt, her IndyCar owner, had also once employed NASCAR driver Cale Yarborough when Yarborough had taken a shot at driving at the Indianapolis 500.

“Rolla had extracted from Cale a promise to check my car out,” Guthrie said by phone. “Well, Cale did take it out and practice, too, and he only went a hair faster than I had been going. ... The car was a real mess. And then here comes Junior Johnson.”

Johnson, a NASCAR icon with moonshining roots, was renowned first as a driver and then as a man who could figure out how to squeeze a few extra miles per hour out of any vehicle.

“Cale and Junior exchanged a few words,” Guthrie said, “in the kind of shorthand people use who have worked together a long time. And I’ll never forget this: Junior looked at Cale, and he looked at me, and he said: ‘Give them the setup.’ And that was a helluva gift.”

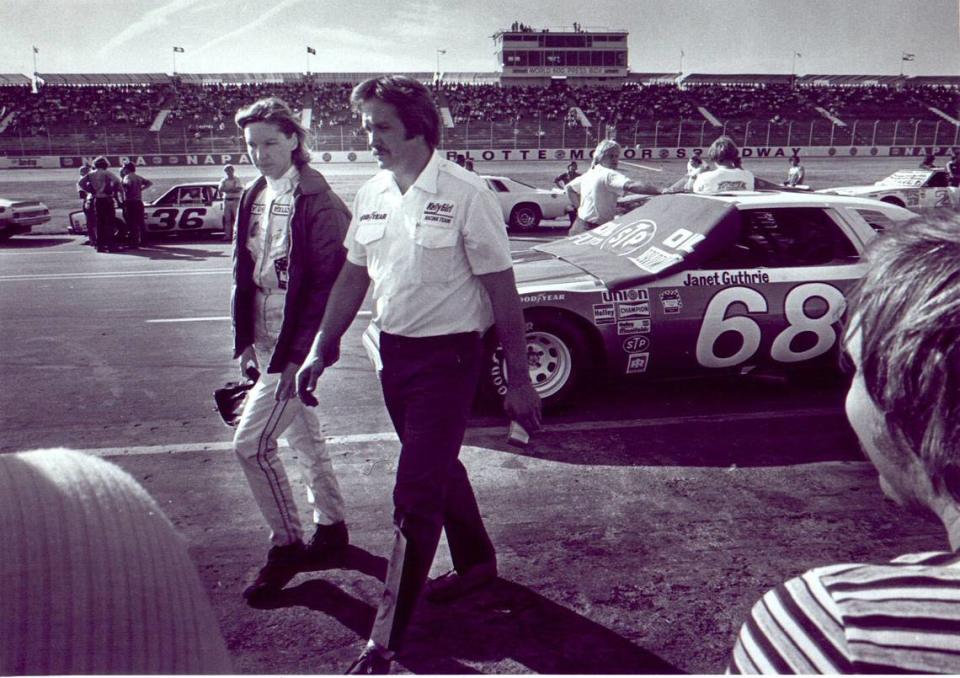

With Johnson actually getting under the hood to do some actual engine revision work himself — Wheeler had also asked Johnson to help Guthrie out — Guthrie’s red No. 68 Chevrolet Chevelle Laguna suddenly became a threat to qualify.

“Junior had sort of a magical hammer,” Wheeler said. “When I heard that hammer ringing out under Guthrie’s hood, I knew progress was being made.”

Many other drivers were skeptical, though, although Guthrie also pointed out that Donnie Allison “was an exception and gave me some invaluable tips.”

When Guthrie set out to qualify on Thursday, three days before the 600, a NASCAR driver named Ed Negre was standing with Moody, Guthrie’s crew chief.

“If she outruns me, I’ll quit,” Negre said, according to a Charlotte Observer story the next day. “I’m not believing a woman can beat me.”

Negre had already qualified at 152.745 miles per hour. Guthrie’s time went up on the scoreboard a few minutes later: 152.797 mph, just an eyelash faster, putting her 27th in the qualifying lineup and Negre 28th.

Negre didn’t quit. But he did run across the infield in embarrassment after seeing her time, followed by the hoots and hollers of various pit crews.

Said Guthrie that day, after she qualified: “I’m really very, very pleased. This is a tremendous thrill. My goal is to drive in important races against top drivers. Now I’m going to get to do that.”

The day of the race

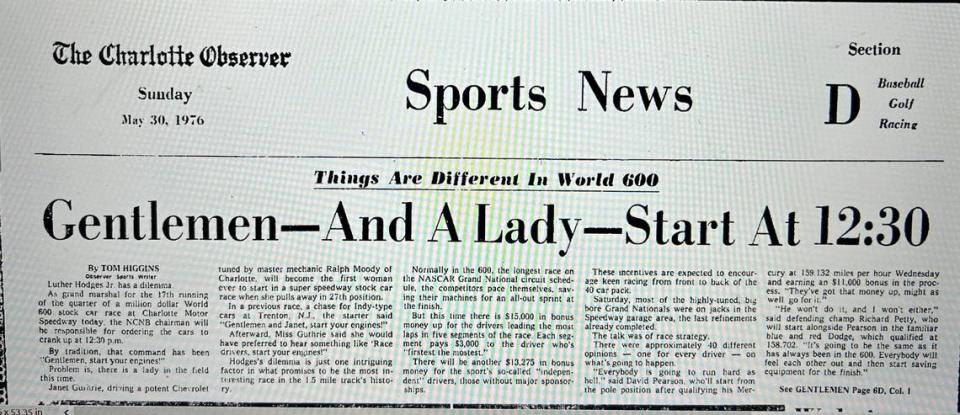

On May 30, 1976, The Charlotte Observer stripped a headline across the front of its sports section that read: “Gentlemen —and a Lady — start at 12:30.”

At the time, the World 600 wasn’t broadcast live on national television. The Indy 500, run on the same day and more or less at the same time, was. However, ABC had agreed to interject occasional updates of the World 600 into its Indy 500 coverage, which tickled Wheeler to no end.

A record crowd of 103,000 showed up to see the race — most were already coming before Guthrie’s last-minute appearance, but certainly her arrival had helped ticket sales to some extent. A number of hurdles had been surmounted, including NASCAR’s initial reluctance to let Guthrie (or her team owner, Ferrari) into the garage where crews worked on cars and talked strategy.

“At that point, women generally weren’t allowed in the garage area,” Wheeler said. “And that’s the way the drivers’ wives mostly liked it. They didn’t want their husbands tempted, so to speak.”

Guthrie was far from the first female driver to ever compete at any NASCAR race. Sara Christian was the first woman driver in NASCAR history, racing way back in 1949, and several others had followed (no woman has won a race at NASCAR’s highest level).

But Guthrie was the first female driver to qualify and race on a superspeedway like Charlotte’s — a 1.5-mile track that was notoriously tough on drivers. That was particularly true for the 600, which required some drivers to ask for relief drivers every year, in the days before cooler firesuits and air conditioners that could calm the ferocious heat inside a racecar’s cockpit.

Whether Guthrie would have the stamina to drive for four-plus hours was very much in doubt. She said she wondered herself.

In the meantime, Pearson had won the pole. A woman from Charlotte named Virginia Andrews had predicted that as well as the next three qualifiers and for that, in a Charlotte Observer contest with more than 2,000 entries, she not only won two $25 tickets to the race, but also a lunch with Pearson and a ride around the track with Pearson in the driver’s seat. Needless to say, newspaper contests with prizes like that have gone the way of the 8-track tape.

By Sunday, Guthrie thought she was reasonably prepared for the race, but she hadn’t known about NASCAR’s dog-and-pony show that is driver introductions. In her previous races all over America, this hadn’t been a big deal. In NASCAR, it was and is enormous.

Guthrie began describing the way it worked to me over the phone, and it sounded similar to how driver introductions are done today. The driver is called on-stage, shakes a few hands and, in 1976, also would often kiss Miss World 600 on the cheek.

To remember exactly what she did that day, she then grabbed a copy of her 2005 book, “A Life At Full Throttle,” and read a passage out loud.

“Through the gauntlet, I went, to the sound of 50,000 cheers and 50,000 boos,” she read. “I shook hands with the official, ignored Miss World 600, was grabbed and kissed by the Winston cigarettes representative and got the hell out of there.”

There are many things in that sentence you might question — kissed by a cigarette representative?! — but let’s keep moving, as Guthrie always has.

‘We need more rookies like her’

As for the race itself, Guthrie more than held her own. Her radio malfunctioned. A couple of drivers tried to intimidate her. The track was blistering hot.

But she drove all four hours and 22 minutes of a race that featured five future NASCAR Hall of Famers finishing in the top 5: Pearson, Petty, Yarborough, Bobby Allison and Benny Parsons. Pearson won slightly under $50,000 for first place; Guthrie got a modest $3,555 for 15th, finishing 21 laps down. Earnhardt finished 31st.

The reaction to her race was mostly positive. “We need more rookies like her,” driver Dave Marcis said. “I feel like she’s raced enough and has enough experience to do a helluva job.”

The exception was Yarborough (who died in 2023). Despite the pre-race help he gave Guthrie, Yarborough said at the end of the race: “It was obvious she was tired. She almost wrecked Pearson a couple of times. She should have quit after halfway.”

When I read that quote to Guthrie a few days ago, she said: “Well, Cale eventually came around. But it took a while.”

Wheeler would consider Guthrie’s run one of the greatest triumphs of his career and a high mark in Charlotte Motor Speedway history. Guthrie would eventually set more records, making the Indy 500 field. Over the course of four part-time seasons at NASCAR’s highest level, she competed in 33 races. She had five Top 10 finishes, did lead some laps and had a career-best sixth place at Bristol in 1977.

“Lack of sponsorship,” Guthrie said, “was what forced me out in the end.”

Even today, after Danica Patrick’s well-publicized foray into NASCAR came and went, no female driver has won a race at the sport’s top level. Although there are some female drivers in the pipeline at lower levels, there will be no women in the field at the Coke 600 on Sunday.

Still, the sport has come a long way from Petty’s attitude in 1976. As Guthrie wrote in her book in 2005, Petty was quoted as saying at the time: “She’s no lady. If she was, she’d be at home. There’s a lot of differences in being a lady and being a woman.”

Now Guthrie receives awards and recognition for her efforts, including the 2024 Landmark Award given to someone who made significant contributions to NASCAR. She couldn’t travel to Charlotte to accept the award in January at the NASCAR Hall of Fame, though, as she doesn’t leave Colorado much anymore and hasn’t wanted to get on a plane since COVID.

When Guthrie remembers that race in 1976, though, she often smiles when she thinks about the end of the day. After finishing 15th and doing her press conference, she was rushed through a throng of supportive fans toward a helicopter. It was waiting to take her to the airport, where a plane would take her back to Indianapolis for a sponsors’ dinner for Vollstedt’s team in Indiana that she had made a condition of racing in Charlotte.

For all she had done before, Guthrie had never ridden in a helicopter. She was amazed by it all — the way it gracefully took off, the fans who turned their faces upward and kept waving at her, the dreamlike feeling of flying.

“A sense of pure elation,” Guthrie would write of the moment, years later.

Fans tossed their caps in the air toward her. She could hear their cheers, even over the helicopter’s noise. Finally the helicopter rose above the grandstands and pointed southwest toward Charlotte’s airport, as the first woman to drive the World 600 soared toward her next adventure.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports