Jane Fonda: ‘I'm very rarely afraid. Maybe emotional intimacy scares me’

When Jane Fonda was arrested in Washington DC last December, days shy of her 82nd birthday, there was an overwhelming sense of history repeating, and not just because this was the fifth time she had been arrested in almost as many weeks. Fonda was taking part in her very public – and ongoing, albeit now online – protest against what she sees as the US government’s criminal inertia over the climate crisis. When he heard about Fonda’s arrests, President Donald Trump crowed to a rally: “They arrested Jane Fonda – nothing changes! I remember 30, 40 years ago they arrested her. She’s always got the handcuffs on, oh man.”

Trump was partially right, although he underestimated the time. Fonda was first arrested in 1970; half a century later she is still protesting, still being arrested and still being mocked by US presidents. On Richard Nixon’s notorious White House tapes, he can be heard discussing Fonda in 1971, dismissing her even more public protests against US involvement in the Vietnam war. “Jane Fonda. What in the world is the matter with Jane Fonda?” he said. “I feel so sorry for Henry Fonda, who’s a nice man. She’s a great actress. She looks pretty. But boy, she’s often on the wrong track.” Less than a year later, Nixon would be taped plotting the Watergate cover-up. Someone should tell Trump that Fonda has an excellent track record of winning the long game, and that her critics don’t.

Still, being derided by the most powerful people on the planet must take some getting used to. Does Fonda ever feel scared?

“The fear part – I don’t know why this is true, but I am very rarely afraid. I’ve been in all kinds of situations: I’ve been shot at, I’ve had bombs dropped on me; but I tend not to be afraid. Maybe emotional intimacy scares me. That’s where my fear lives,” she says from her home in Los Angeles, with a self-mocking laugh.

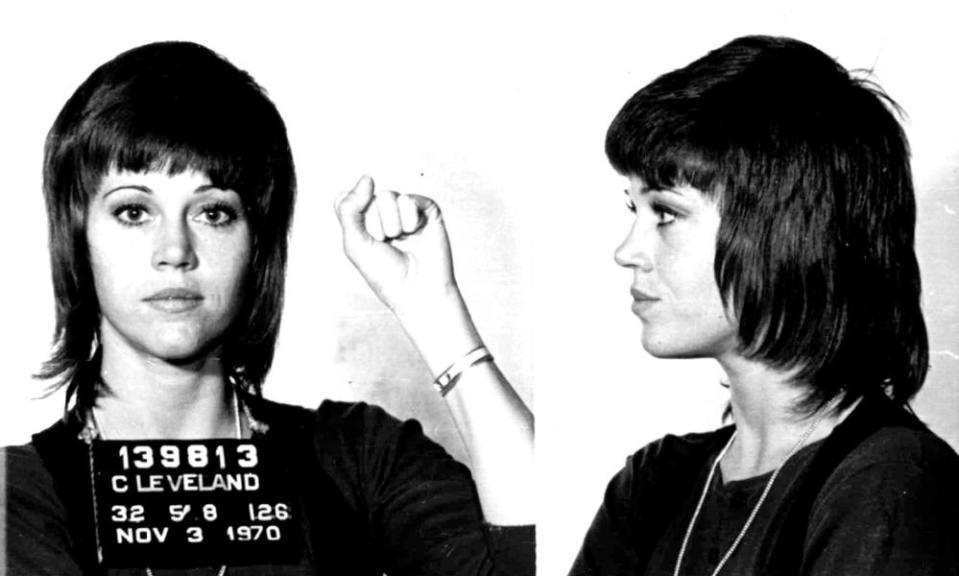

My fear lives, a tiny bit, in the prospect of interviewing Fonda, precisely because she is so fearless. The first time she was arrested, it was because officials insisted the vitamins in her suitcase were illegal drugs. “I’m taking orders from Washington!” one of the customs officials shouted at her – yet she was so undaunted she raised and clenched her fist in her still iconic mugshot.

What was she thinking when they took that photograph? “Defiance,” she replies firmly, and adds, “I’m just glad the lighting was good!”

How does she feel when she looks at the notorious photographs of her in Hanoi in 1972, sitting behind an enemy anti-aircraft gun as if she were about to shoot down US planes, which led to decades of vilification. “I want to throw up. I understand why that girl… why that happened. But it just sickens me, the whole thing. But do I regret going? No, never. It was the most life-altering experience I could ever, ever have.” She apologised a long time ago for sitting behind the North Vietnamese guns, but continued to protest against the war, even though people demonstrated outside her films for years to come.

She has won two Oscars (for Klute and Coming Home), but Fonda’s extraordinary life has, for many, long overshadowed her career. To some, she will for ever be Hanoi Jane; for others, she is the queen of aerobics. To this day, Jane Fonda’s Workout remains one of the biggest-selling home videos ever. But Fonda only made it to raise money for the Campaign for Economic Democracy (CED), the non-profit organisation she ran with her second husband, the radical left-wing firebrand Tom Hayden. Wealthy housewives doing pelvic thrusts to the Workout had no idea they were contributing to a cause that wasn’t a million miles from socialism, and Fonda raised more than $17m for the CED. (In classic man-of-the-left style, Hayden occasionally made “disparaging remarks” about the Workout. “I would just think, OK, I’m vain. [But] where else would you have got $17m?” Fonda writes in her 2005 memoir, My Life So Far.)

As if to prove how little things change, during lockdown Fonda has been making workout TikToks to raise awareness of her environmental protests, still exercising for activism at 82. “It’s fun and it attracts a younger demographic, doing TikTok,” she says, with the breeziness of one fully fluent in social media.

Fonda still looks astonishingly like her father and, with those high cheekbones and dark brows, she has the demeanour – as Henry did – of someone who does not suffer fools. “In addition to being funny and fun, boy is she ever honest, frank, available and a total straight shooter,” Sam Waterston, her co-star in the excellent sitcom Grace And Frankie tells me.

Fonda has a new book out, called What Can I Do? I tried to count the number of books she has published and I think it’s a dozen, but neither of us is sure. On the surface, they seem a somewhat random mix, from a guide to being a teenage girl to the Workout books. But every one is underpinned by Fonda’s activism. Being A Teen was partially born out of her work with her foundation, the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power & Potential (GCAPP), set up in the 90s to help reduce the state’s high rates of teen pregnancy. The Workout books were Das Kapital smuggled inside a leotard (sort of).

While it is easy to mock celebrity activism, no one can doubt Fonda’s bona fides; she has been shouting about the environment since the 1960s, after learning that car emissions damaged the atmosphere. But why keep doing it? Why endure prison with its metal slab of a bed (“I’m quite bony, so that was painful,” she admits) instead of enjoying a nice, quiet life in her ninth decade?

“Oh my God, for my own sanity! Last year, I was going insane, I was so depressed, knowing things were falling apart and I wasn’t doing enough. Once I decided what to do, all that dropped away,” she says.

What Can I Do? is a how-to guide and memoir of her protest campaign, known as Fire Drill Friday. This took place in Washington DC every Friday in late 2019, and led to the arrest of Fonda and many of her celebrity friends, including Waterston. “When we heard what she was planning, we all volunteered,” he says. “Jane is one of those people who walks toward the fire. She’s out to make a difference.”

It takes more than a global plague to break Fonda’s stride, and her first online climate protest was so popular the website crashed. “Can you believe it, a quarter of a million people follow us! This is not what I expected. I’m so busy, I can spend the entire day sitting at my desk on Zoom meetings. I need to go back to work so I can have more time,” she says, referring to Grace And Frankie, which starts shooting again this autumn.

In her book, Fonda details her endearingly earnest attempts to get to grips with the climate crisis. But my favourite moments are when she laughs at herself, such as when she catches up on her wall squats in prison (“Hey, you gotta seize the opportunity”). “Well, there’s a lot to laugh at! If I didn’t laugh at myself I’d be crying,” she says.

In January 2018, she posted a photo of herself on Instagram, looking distinctly bedraggled in a designer evening dress she had worn the night before. “Here’s me the next morning. I couldn’t get my dress unzipped so I slept in it… Never wanted a husband in my life until now,” she wrote.

“Haha, you saw that?” she cackles.

I not only saw it, I discussed it with Dolly Parton, Fonda’s co-star in 9 to 5, when I interviewed her last year. She said she admired it, but would never do that herself. “I thought it was cute, but no, never!” she gasped.

“Ha! That doesn’t surprise me. I once spent 10 days with Dolly on her tour bus and never saw her without full regalia,” Fonda says, laughing.

Parton and I also talked about the time she, Fonda and their other 9 to 5 co-star, Lily Tomlin, presented an award at the 2017 Emmys, with an on-the-nose swipe at Donald Trump.

“Back in 1980 in [9 to 5], we refused to be controlled by a sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot,” said Fonda.

“And in 2017, we still refuse to be controlled by a sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot,” added Tomlin. The audience cheered and Parton – doubtless thinking of her southern Republican fanbase – went wide-eyed with alarm.

“I just did not want everybody to think that whatever Lily and Jane think is what I think,” Parton later told me. “I don’t really like getting up on TV and saying political things.”

I ask Fonda if she and Tomlin had taken Parton by surprise.

“Oh no, we planned it before. But I think [Parton] got a reaction and that’s what upset her. I don’t think she thought at the time about that reaction,” says Fonda blithely, unintentionally getting her co-star into trouble again.

***

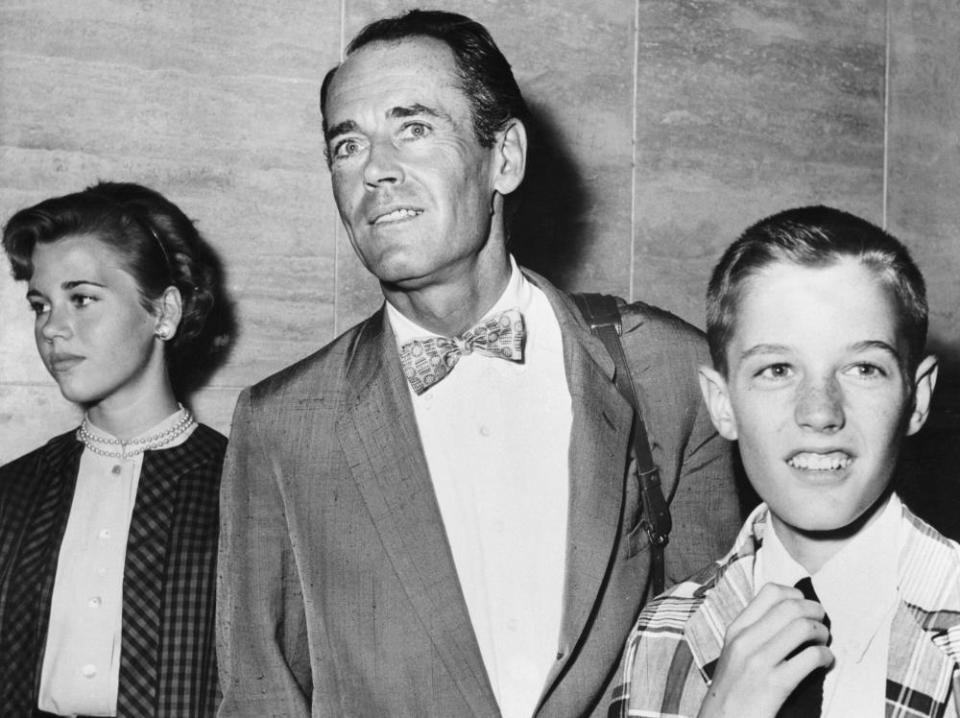

Whenever Fonda tells her life story, she has to start with her father, Henry. A second world war veteran, he was regarded by the public as an American hero, the only actor who could have played both Tom Joad in The Grapes Of Wrath and Davis, the truth-seeking juror in 12 Angry Men. In her memoir, Fonda writes that her father once “kicked in the television set” when the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings were being broadcast. Yet, she adds, he didn’t join other celebrities who flew to Washington DC, where the HUAC hearing were taking place, to publicly support the writers and directors accused of communist sympathies, known as the Hollywood Ten. Given how political she is, does Fonda find that strange in retrospect?

“Oh no. For him, voting for the Democratic candidate who promised to end the war was what he felt comfortable doing. And he did that. It was a generational thing, I think,” Fonda says protectively. (I don’t have the heart to point out that others of Henry’s generation spoke out against HUAC, including Humphrey Bogart and John Huston.)

But she revered her father and felt “in his shadow for years”. It was a long shadow, even if Henry was occasionally more of a theoretical than actual presence during her childhood, leaving her, her younger brother, Peter, and their mother, Frances, for work and, later, for other women. When Fonda was 12, her mother killed herself. Soon afterwards, Henry dispatched his children to boarding school; he and Jane never spoke about Frances again.

Fonda spent much of her life trying to get her father to see things from her perspective, with limited success. Her Vietnam protests were an especial source of rancour between them. “I tried to make him understand. He just couldn’t. I told him what I was hearing from soldiers who had been in Vietnam about the atrocities. He had said, ‘If you can prove to me this is true, I will lead a demonstration to the White House.’ So I brought in a Green Beret who talked to him about it – but still he just couldn’t. It wasn’t his style,” she says.

I ask if she ever rewatches On Golden Pond, the 1981 movie in which the Fondas play an emotionally reserved father and headstrong daughter.

“On Golden Pond? I rewatch it all the time. And I… ” Fonda breaks off, sobbing. “God, even talking about it!” she begins, but has to stop again.

I tell her I’m so sorry: I didn’t mean to make her cry.

“Oh, that’s OK. Nothing wrong with crying,” she says.

Exercise was for me a healthy way to control my body in a way I couldn’t do otherwise

I tell her I always cry at On Golden Pond, too, and always at the scene when the daughter touches her father’s arm and he looks down, as if suppressing tears. (In Fonda’s memoir, she says she improvised that gesture, and that her father’s tears were real.)

“Oh God, I know. I’m just the luckiest person in the world. The fact that I was able to do that movie with him right before he died, because he died five months later,” she says, choking up again.

Both Fondas were nominated for Oscars for the film, but only Henry won, his first and last Academy Award. He was too ill to attend the ceremony, so Fonda accepted it on his behalf. It was, she has said, “the happiest moment of my life”.

It is a testament to Henry’s influence that both Fonda and her brother, Peter, went into acting (as did Peter’s daughter, Bridget, and Fonda and Hayden’s son, Troy Garity.) Peter died last year at the age of 79. Were they close?

“Yes and no. We were very different. I didn’t see a lot of him. I didn’t even know that he was sick. But he eventually sent me an email and said what hospital he was in, a few weeks before he died. I went there almost every day, and we would laugh and laugh. I’m so grateful that that’s how it was at the end between us.”

As much as she adored her father, Fonda is clear-eyed about him. “Dad had an obsession with women being thin. Once I hit adolescence, the only time my father ever referred to how I looked was when he thought I was too fat,” she writes in her memoir. She learned from an early age that if she didn’t show hurt or need, she would be praised for being strong; she learned so well that, even when her mother died, she didn’t cry. But pain resists repression. At boarding school, Fonda embarked on a 30-year struggle with bulimia, finally kicking it in her 40s.

I tell her I, too, developed an eating disorder as a teenager, and that I’m grateful to her for talking about how long it really takes to recover.

“Oh yeah – years! It was so hard to do. I remember Jason Robards, who had been a terrible alcoholic, talking about the third step of the AA programme, the higher power. And I always thought, what a lot of bullshit. I discovered later, that it is true,” she says.

So it was faith that finally helped her stop being bulimic?

“It was a combination of a lot of things. Part of it was willpower, but it happened more when I received a spirit. I was suffering terribly and – God, this is so weird to say to the Guardian! – but I was alone in my house and I had really hit bottom. I said out loud, ‘There must be a reason that God wants me to suffer like this.’ And I looked around and said, ‘Who said that? I’m an atheist!’

I always wanted to date someone who was the opposite of my father. I didn’t realise I picked men who were just like him

“But right at that time, everything began to change. I’d had an epiphany, I could feel it happening in my body. I could feel myself coming together and being one person. You know, it’s like you look at a double exposure and slowly the doubleness comes together and they sit perfectly. That’s what happened. It’s the absence of that which causes the anxiety that leads to eating disorders,” she says. In 2001, Fonda became a Christian.

“But how about you? Are you OK now?” she asks.

I tell her I’m fine, although it wasn’t a higher power that helped: it was having kids – suddenly there were people who needed me to eat. I apologise for how unfeminist that must sound. “No! Not at all. It’s totally true, I get it,” she says with feeling.

Fonda’s recovery from bulimia was closely followed by her embrace of aerobics. Was she swapping one form of body obsession for another? “I think exercise was for me a healthy way to control my body in a way I couldn’t do otherwise,” she says.

She has talked in the past about having facelifts and breast implants. Was the plastic surgery another way to punish her body? “Oh yeah, plastic surgery, that’s interesting. Well, no matter what I do, I’m stuck with this [idea]: if you don’t look right, you’re not going to be loved. So I always wanted to try to look right. I think when you’re poor you cut yourself, and when you’re rich you have plastic surgery,” she says.

***

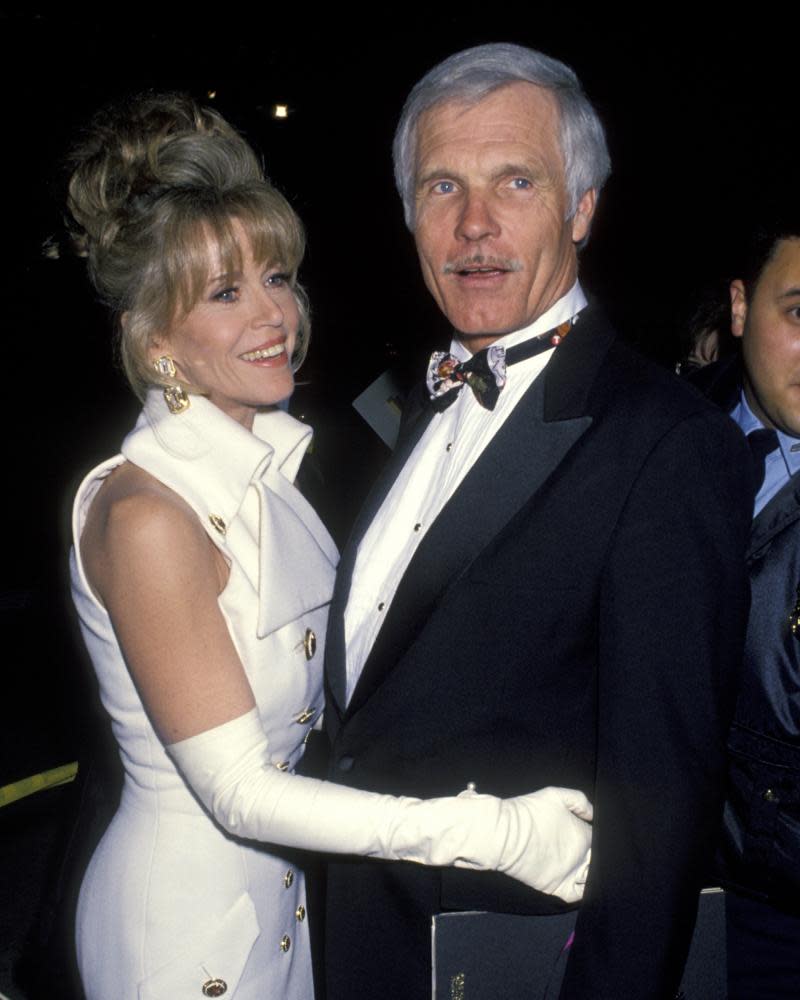

As an adult, Fonda swapped one dominating male figure for three: her husbands. When she was with the film director Roger Vadim, who was previously married to Brigitte Bardot, she became a Bardot-esque sex kitten in Barbarella and engaged in threesomes with him, eventually leaving him after the birth of their daughter, Vanessa. Married to Hayden, she took to the barricades with him. When she married media mogul Ted Turner in 1991, she swapped her off-grid life for that of a billionaire’s wife.

“I always wanted to date someone who was the opposite of my father,” she explains. “I didn’t realise that, in the ways that really mattered, I picked men who were just like him because they all had a hard time with intimacy.”

Fonda says she and her father never talked about her mother because she was scared of hurting him, and that she also struggled to express her feelings to her husbands. And yet she was out loudly campaigning for American GIs to come home from Vietnam, for girls to have better sex education, for indigenous fishing rights.

“Yes, but that was an external courage. It wasn’t about my heart,” she says.

I had read Fonda’s memoir directly before reading What Can I Do?, and it was jarring to go from her tales of near daily private jets with Turner, to urgent warnings about the environment. Does she have regrets about that period of her life?

There is a long pause. “I wouldn’t have given up a moment of it, for anything. I mean, he owns two million acres, OK? I used to try to imagine what they would be if he hadn’t been able to buy them. There would be, how many McMansions? He saved all this land and the only way he could get around to them all was to have his own plane. So I didn’t mind it,” she says.

Instead of slogging it out with all these protests and arrests, why not ask Turner to donate, say, half a billion dollars to environmental causes? Surely that would achieve at least as much.

It’s the most exciting thing in the world to keep learning! It’s more important to be interested than to be interesting

“Yes, um, I have not asked him. He has a family foundation and, you know, all family foundations have hit hard times now. So no, I don’t go to him for money,” she says in the careful, ever-so-slightly strained voice she uses whenever we talk about Turner. Their relationship sounds if not controlling then certainly restrictive, with Turner scheduling every hour of their days months in advance. He insisted she always be by his side, and Fonda made no films during their marriage, which ended when she left him in 2001. He then flew her in his private plane from his ranch to Atlanta, Georgia. His new girlfriend, who – unbeknown to Fonda – had been waiting in the airport, flew back with him to his ranch in Fonda’s still-warm seat.

In the past, Fonda has said that she allied herself to strong men because she felt so unsure of herself. But isn’t it more likely that she needed strong people because she is an extraordinarily strong character herself?

“Oh yeah, whenever I’ve been with men who are not strong I’ve had a really hard time,” she agrees. “I’m now five years older than my dad was when he died and I’ve realised that I am, in fact, stronger than he was. I’m stronger than all the men that I’ve been married to.”

These days, Fonda is firmly single. “[That part of my life] is gone. I can tell. It’s just over – I’ve closed up shop. I’m extremely happy on my own,” she says. A common refrain in her memoir is that she allowed her husbands to shape her too much because of her “disease to please”. Another way to look at it is that she is just admirably open to new experiences: with Vadim, she embodied the sexual experimentation of the 1960s; with Hayden, 1970s activism; and with Turner, the monied life of the new 1990s elite. Now she is eagerly learning from a new generation of activists. Shortly before our interview, she posted on Instagram a speech she made with Patrisse Cullors, one of the co-founders of Black Lives Matter; during lockdown she has hosted Fire Drill Friday events with trans activists.

“Oh, it’s the most exciting thing in the world, to keep learning!” she says. “It’s one of my mantras: it’s more important to be interested than to be interesting. I feel like a student and that’s really good. All these young people are so good at knowing what to do and not to do, what to say and what not to say, and they provide tremendous insight. I’m just learning so much every day and it makes me so happy. It’s a whole new chapter.”

• What Can I Do? The Truth About Climate Change And How To Fix It, by Jane Fonda, is published by HQ on 8 September, £20. To order a copy for £17.40, go to Guardianbookshop.com

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports