Game Changers, Part Three: The best defence is offence

How is junior hockey developing a new generation of NHL player like Connor McDavid? Yahoo Sports is publishing a three-part series speaking to coaches and GMs – many of whom are former NHLers – across the Canadian Hockey League to find out how the game is changing.

When Darren Rumble was patrolling the blue line in the NHL during the mid-1990s, he vividly remembers playing against a fellow defenceman named Greg Hawgood.

Listed generously at 5-foot-10, Hawgood managed to carve out an impressive pro career with more than 450 games in the NHL at time when small defencemen were a rarity.

“He was so good that he would sit on the bench for the whole game and just play the power play,” recalls Rumble. “He was too good to play in the minors, but he was super small. He could run a power play like nobody else.

“He couldn’t take a regular shift because he wasn’t big enough. Now (in today’s game) he’d be up for the top defenceman award.”

That’s how much the game has changed on the blue line.

There was a time when bigger was better when it came to defencemen. The thought of drafting an undersized – sub-six-foot – defender was unheard of in the NHL. Hawgood, for example, was a 10th-round pick, taken 202nd overall by Boston in 1986 despite being the reigning CHL defenceman of the year, winning a Western Hockey League championship with Kamloops and a gold medal with the Canadian world junior team.

The market at the time was weighted towards the big, stay-at-home, defensive defenceman. There was a major shift more than a decade ago when the NHL decided to remove the red line and open up the ice. The same was true in junior hockey, where many of those NHL defencemen were being developed.

The focus, under the new rules, was to bring a faster, more exciting brand of hockey to fans. Skating, speed, and the ability to carry the puck became more coveted than size. There was also a crackdown on obstruction – the hooking and holding – that were a trademark of the 1980s and ’90s.

“Taking the obstruction out has probably impacted the defensive game more than anything because you used to be able to pivot with a guy and then latch your stick on and basically water-ski back to the net,” said Rumble, now head coach of the QMJHL’s Moncton Wildcats. “You would hook him or hold him up.”

Moves like the “can-opener” used by many a defenceman and turned into an art form by the likes of ex-Leafs defender Bryan McCabe, have been reduced to nostalgic views on YouTube.

“The big (defenceman) that could latch on to a guy and hook and hold and impede people for whoever was getting the puck, that guy can’t play anymore because he’s going to be in the penalty box all night,” said Rumble. “If he can’t skate, guys are going to be blowing past him because he can’t use his stick anymore the way he used to be able to.”

As a result, opportunities that were once denied smaller junior defencemen opened up in the NHL as long as they could skate well and move the puck. It also changed the way coaches approached the game. There was more focus on offence and using team speed to create mistakes or catch opponents flat-footed.

Former NHL defenceman Jason Smith said teams are looking to play a high-tempo game and that includes utilizing defencemen more than ever.

“Now you might have one player on the ice that’s kind of a safe guy or a safe play, which would be a simple chip play up the wall to a stationary player where you’ve got two other players in motion and you’ve got a defenceman that’s actively joining,” said Smith, a former captain with the Oilers and Flyers and now head coach of the WHL’s Kelowna Rockets. “You’ve got more outs that are moving full speed as opposed to standing still and chipping the puck in and getting after it.”

It’s even created a change in thinking for some junior coaches since the game is weighted towards creating offence (whether or not more goals are being scored is another story). There’s more focus on attacking, to the point where most teams will add a defenceman into the mix to essentially have four players in the play at any one time.

“It’s always hard to score on a three-man rush, you always need that fourth guy,” said Sarnia Sting head coach Derian Hatcher, a 16-year NHL defenceman. “That’s just reality of the game if you want to score goals now.”

The new adage: the best defence is a good offence.

“The games are coached so well defensively now that if your (defencemen) aren’t jumping in a whole lot it’s easy for the coverage, for the other team’s defencemen and backcheckers to pick up the coverage,” said Seattle Thunderbirds head coach Steve Konowalchuk, a former NHLer. “You have to engage that fourth guy to try to create some breakdowns. I don’t know necessarily if that’s because of the speed or more so because of video (as a coaching tool). It’s so easy to teach defensive play now compared to what it was 10 or 15 years ago.”

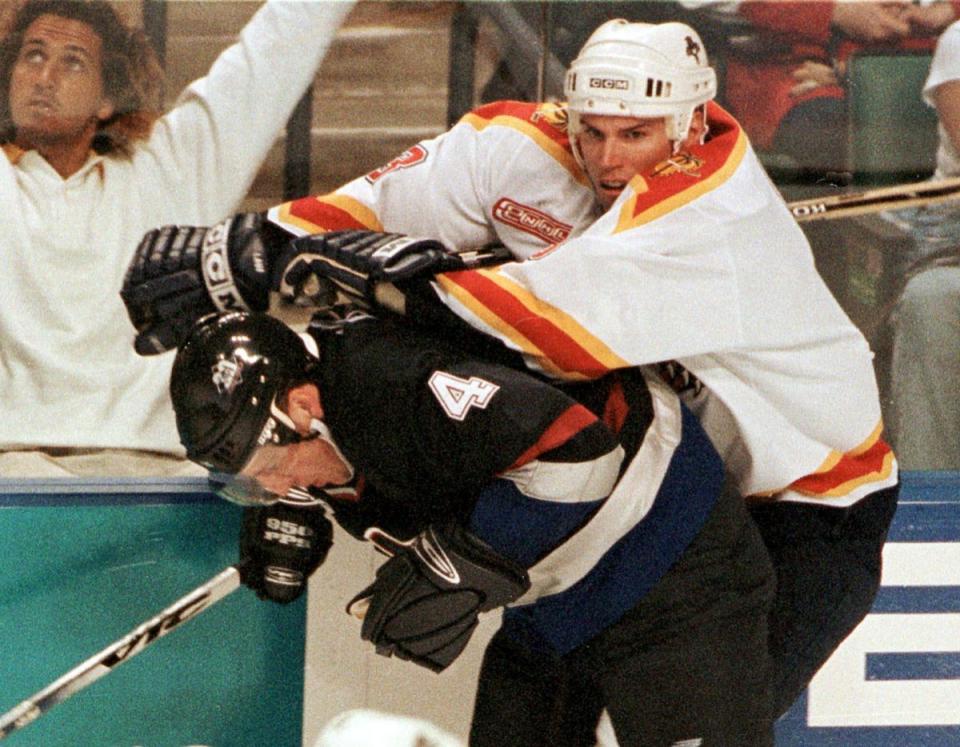

The speed of the game, the constant attack and the crackdown on the old “clutch and grab” have also made it more dangerous for defencemen. In the old days when the puck went into a corner, one defender would retrieve it while his partner would impede the first opponent in on the forecheck to slow him down. It would give the retrieving defenceman the time to move the puck safely.

Now, the onus is on the retrieving defenceman to move to the puck quickly to beat the forecheck or prepare to be leveled. And in an ironic twist, it’s often bigger forwards looking to crush smaller defencemen.

So Rumble has been diligent about teaching his own defencemen in Moncton how to take a hit.

“It’s all about protecting yourself and absorbing (the hit),” said Rumble, who played close to 200 NHL games. “That’s a learned skill because you can’t allow yourself to be vulnerable and get smoked or you’ll be in the stands on injured reserve for your whole career. It’s those 50-50 races (to the puck) or the ones where you might just win to give the forechecker a green light to run you through the end boards – you’ve got to learn to absorb those, protect yourself and protect the puck because you don’t want to turn the puck over.”

Going to retrieve a puck for a defenceman is almost a constant race as teams focus more on using speed and numbers as a way to create turnovers and gain puck possession. The faster a defenceman can move the puck out, the less defending necessary.

“There’s more emphasis on getting on the other team’s (defence) quickly to make sure they don’t have time,” said Konowalchuk. “You have to teach your defencemen to make sure you keep everyone ahead of you. You count numbers a little more than in the past because guys are taking off.”

The way the game is being called now has also opened up the front of the net for forwards, allowing them to park themselves there without any consequence. Before, standing in front of the net meant withstanding a constant barrage of spine-crushing cross-checks to the back. Now, as Rumble notes, the front of the net has become “the safest place in the rink.” Subsequently, defencemen are no longer standing between the goaltender and attacking forward to prevent goals.

“Defencemen now leave the guy in front of the net and step out in front to block pucks,” said Rumble. “They’re basically willing to leave their guy alone in front in an attempt to block the puck and not let it get to the net. The shot-blocking has probably gone up 10-fold.”

There’s also a little less man-on-man coverage in the defensive zone. Coaches today talk about playing in layers starting in the neutral zone, so there’s protection if a defensive breakdown occurs.

“I think overall team defence in the neutral zone has become the biggest change (in defending),” said Hatcher, who won a Stanley Cup with the Dallas Stars in 1999. “If you see how teams play now they’re right on top of guys and that all starts in the neutral zone and how you defend it without the red line.”

The prevalence of video in coaching has not only made it easier to teach players to defend, but it’s also made it easier for coaches to find weaknesses and capitalize on them.

“Coaches have figured out that the best way to counteract skill is to take away time and space,” said Rumble. “It doesn’t matter how good you are, if you don’t have time and space it’s difficult to make a play.”

Game Changers, Part One: Life Without The Red Line

Game Changers, Part Two: Video Explosion A Quantum Leap For Coaching

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports