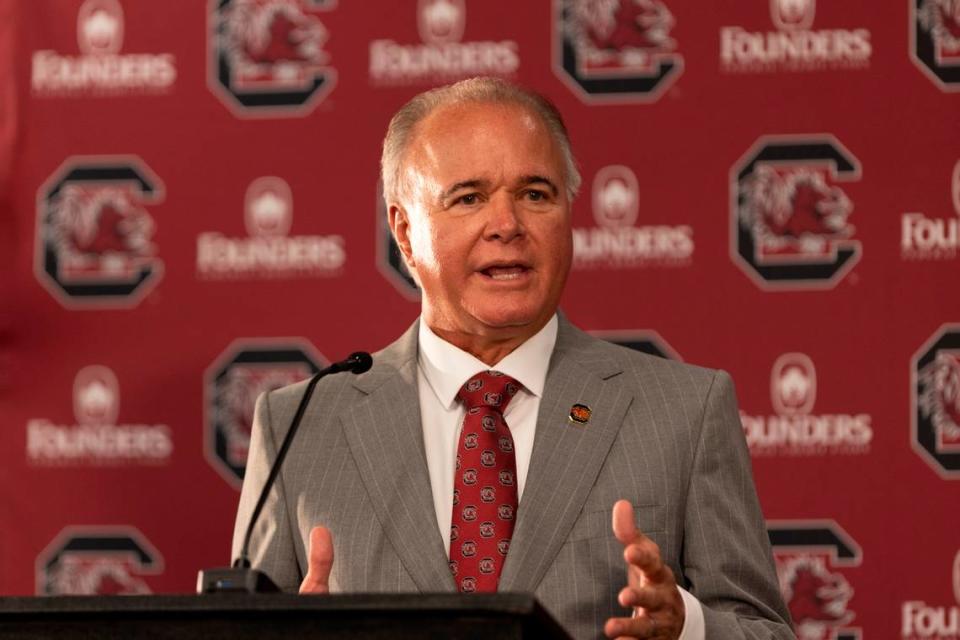

A final act: The question Paul Mainieri came to South Carolina to answer

Paul Mainieri was standing underneath a goal post as Notre Dame played Michigan, listening to a story about Lou Holtz.

Tony Rice — best known as being the last quarterback to lead the Fighting Irish to a national championship — was telling the then-Notre Dame baseball coach how he and his teammates revered game days. The pageantry was marvelous, but there were refs and rules that made it so Holtz “had to stay behind the sidelines,” Rice said.

“Practices were miserable,” Rice told Mainieri, “because you could never do it as well as he wanted you to do it. He put so much pressure on you at practices, the games were easy.”

Mainieri never forgot that.

He’d go on to lead Notre Dame to a College World Series then take LSU to five more, including a national championship in 2009. He ran his win total to over 1,500, earning victories in five different decades by running competitive, game-like practices and “letting players know when what they’re doing isn’t good enough.”

Which brings us to 2024, to Mainieri’s reemergence into the college baseball world after taking the head coaching job at South Carolina earlier this month. The news wasn’t met with skepticism but, rather, genuine questions — most of which don’t seem to be real concerns for Mainieri.

Is Mainieri healthy enough to coach? Can he sustain the rigor of the job at 66? Can he float into the new world of college baseball with unlimited transfers and NIL and adapt?

Those inquiries don’t seem to worry Mainieri.

Yes, he retired from LSU in 2021 because of neck pain and chronic headaches, but its drastically subsided since an ablation procedure in 2021. Basically, doctors heated a metal rod to 200 degrees and burned the ends of the nerves attached to Mainieri’s vertebrae. As long as he’s moving his neck, he feels fine, playing golf almost daily for years.

Of course, too, he’s heard the age thing. First off, he is not 100 and he isn’t planning on being in this job for a decade. Years ago, he said he wanted to retire at LSU when he was 66 — which would have been after this past season — but things change.

The past three years, he’s lived the retirement dream. He went to the Masters and The Players golf tournaments. He went to the College World Series with his wife, Karen. He golfed his way through Scotland. Still, he yearned for another shot at coaching. To go out on his own terms.

As for adapting, Mainieri scoffs. He’s been adapting his entire coaching life. He adapted to players having cellphones. To social media. To agents. To scholarship reductions. To the start of the transfer portal. Why would NIL all of a sudden give him fits? Plus, Mainieri said, “I want the challenge to see what it’s like coaching in this era.”

But one question he doesn’t have such a definitive answer about, a query less about baseball than sociology: Can the same coaching style he employed his entire career — discipline-oriented where perfection is the only goal — still work with kids in 2024?

“We’re gonna find out,” Mainieri said.

‘He chases perfection’

Nearly 25 years after Mainieri stood in Notre Dame Stadium hearing a story about Holtz, others are telling eerily-similar stories about Mainieri.

“When we played at LSU,” said former Tigers shortstop Kramer Robertson, “all of our teams couldn’t wait until gameday. The games were easy. The practices not so much. He chases perfection knowing you’re never going to get that.”

Robertson loves to tell the story that, as a freshman, he was turning double plays with Alex Bregman on his own time. Mainieri saw it, called Robertson into his office and said the technique made him want to vomit.

An LSU player on Mainieri’s first team in Baton Rouge, Blake Dean bombed 56 home runs as a Tiger. He was a slugger, destined to hit in the 3-hole. He arrived to college not knowing how to bunt, because why on Earth would he ever bunt? That didn’t fly with Mainieri. Everyone has to know to bunt.

“He told me it was the most embarrassing thing he’s ever watched that I couldn’t bunt,” Dean said, “and to get off the field and not to hit batting practice until I learned how to bunt.”

Years later, LSU was playing Vanderbilt and the Commodores decided to put a shift on when Dean came up. Mainieri signaled for a bunt. Dean tells the story with such reverence because he didn’t just bunt — he got a hit.

That is Mainieri’s philosophy in action. Guys need to feel pressure in practice, feel like what they’re doing isn’t good enough. Because then they’ll work and work at it. And then they’ve practiced it under scrutiny for so long that they can execute when 8,000 people are hollering and a ground ball is hit their way. Or they can get down a bunt at any time — or maybe just one time.

Mainieri’s practices are detailed. They are long. They are intense. They yield results.

First he gives the field to the pitchers, who warm up with long toss then work on fielding and pickoff moves. While that’s going on, there’s a chance everyone else is inside a classroom being taught Baseball 101 by Professor Mainieri.

During scrimmages from the day prior, Mainieri will flag plays or situations he wants to talk through, then someone will get the videos of those and queue them up for the professor.

“We’ll analyze the way we ran the bases or analyze the way the defense reacted to the play,” Mainieri told the “Inside the Gamecocks Show.” “Just use it as a teaching tool.”

When everyone finally gets on the field, Mainieri goes into a new block. Maybe it’s working on getting a jump off first base. Or pop-fly communication. “I’ve got a long list of fundamentals I’ve got mapped out.”

During batting practice, everyone has a role, including pitchers.

After that, almost every practice will end with some sort of scrimmage. Just because you’re great at drills but it means nothing if it isn’t applied to actual game situations. And that provides the clips for the next day’s Baseball 101.

“I want the players to have instincts for the game,” Mainieri said. “Before you know it, that’s a four-hour practice.”

Returning to teach Baseball 101

In his three years out of the dugout, Mainieri would grow irate watching games. Mad that coaches were tolerating kids not hustling, that they were OK with guys not running out grounders, not backing up bases.

He’d think to himself, “It must be impossible to coach these kids because of their sense of entitlement and NIL money and you don’t have to wait very long to hear about some coach being fired for being too hard on players.”

Then he’d sit back and think no way. There is no chance that kids don’t still want to have structure in their lives, that they don’t want to have someone care about them enough to not just pat them on the back every time they take a sip of water.

This is his chance to find out. He is coaching at South Carolina because he wasn’t happy with the way things ended at LSU, wasn’t filled with joy in retirement. But he is also coaching at South Carolina to prove himself right.

“Part of my motivation for coming back,” Mainieri said, “was seeing if I still can relate to a bunch of 18- to 22-year-olds that will understand that I care about them and want the best for them.”

Mainieri wants to see if he can win in the way he’s always won. By making sure his players are seeking excellence and to get on them in the moments they’re not. That means correcting them if their not hustling, not playing smart, not playing with instinct.

And, from Mainieri’s experience, his players are frustrated at first and years later will thank him for impacting their lives so much. It’s why over 1,000 texts flooded his phone after he took the South Carolina job. It’s why Robertson calls him a father figure and says no ones had a bigger impact on his baseball career.

Mainieri sees no other way to affect the success of his team. “I’m not a potted plant,” he jokes.

“Listen,” he added, “I’ll encourage a kid to go into the portal if he’s not gonna play the game the right way. And I’m not asking for too much.”

Willing to take a risk

Mainieri has never been one afraid to bet on himself.

One night during the summer of 2006, Mainieri called his accountant.

It was urgent. He was considering leaving Notre Dame to take the LSU job. But the finances were messy. The coach was making just under $150,000 a year at the most prominent Catholic school in America, he had three years left on his contract and, oddly, his buyout was all the money left on the contract.

Almost 20 years later, he doesn’t need but a half second to remember the number.

“$446,000,” he says.

That and his two daughters, Samantha (Notre Dame) and Alexandra (Ball State) were set to get free tuition because Mainieri had been employed at Notre Dame for 12 years. The LSU job would create over $100,000 in unexpected costs — at the least.

“(My accountant) said, ‘It’s gonna take you four-and-a-half years to get whole,’ ” Mainieri said. “And that’s not including the debt I incurred by buying a much bigger house. … By taking the job at LSU, I went like $1.2 million in debt.”

In other words: Don’t get fired in five years. Which, looking back, seems silly. But the coach Mainieri replaced, Smoke Laval, lasted exactly five years before getting canned.

Mainieri, as you know, took the LSU job. He lasted 15 years and, by year five, had been to Omaha twice and won a national title.

“You’ve got to gamble on yourself,” Mainieri said.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports