My Father's Ghost and the Chelsea Hotel

Growing up in the Chelsea Hotel, I often saw ghosts. They came in the form of artwork. The building was packed full of art —a strange aggregation of periods, mediums, and styles. There was a temporality to the collection. Like a slow game of musical chairs, over time, they were rotated to various locations throughout. The pieces were displayed in a reverse cascade that tumbled up the giant spiral staircase, unfurling into the hallways of each floor. Artists hung their work within the vicinity of the apartments—sometimes closet-size SROs—they rented in the Chelsea.

The art was gifted to Stanley Bard, the managing shareholder of the building, or to the hotel collection itself, depending on whom you ask. Some pieces were taken away by the resident artists once they moved out. And others occupied a liminal space: No one knew who they belonged to or why they were left behind. Had the resident fled in the night, having finally been threatened with eviction after years of not paying rent? Had he simply forgotten the work or, worse, died? Such was the enigmatic nature of the artists and their residencies at the hotel.

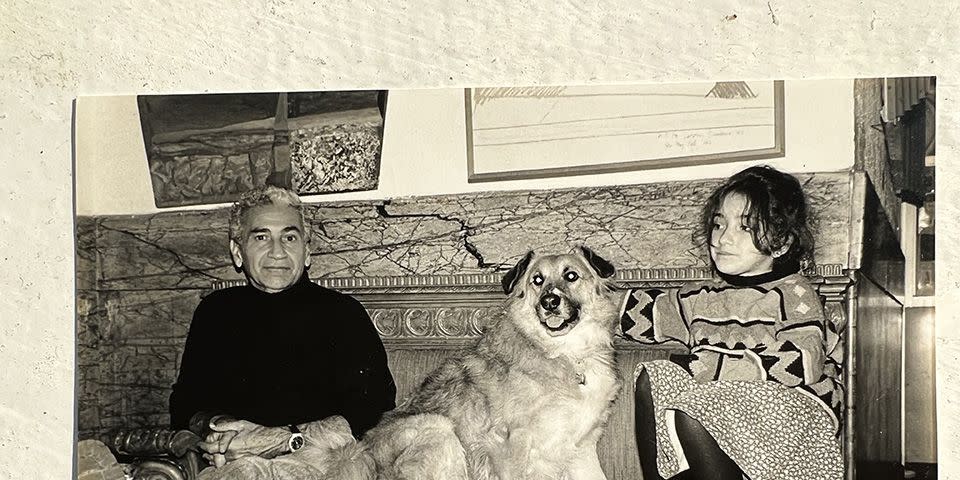

In a black-and-white photo from 1983, a painting with a series of repeating, upside-down rainbows hangs in the place of the papier-mâché “wound” sculpture. Pinchas Burstein, a Polish survivor of Auschwitz (later known as Maryan S. Maryan) hung his spitting military man, a mockery of the Nazi Party. Below is a sculpture of a bird (or is it the top of a totem pole?), wings outstretched.

There used to be a bookcase, half obscured by a large tropical plant, in the lobby. Looking at it evokes a haptic experience for me. On each shelf is a table setting: one all in blue, another in red, and so on. I remember my curious, child fingers nudging the objects in confusion, mistaking them for a glued-down Fisher-Price tea set. My hands came away coated with tacky dust and grime.

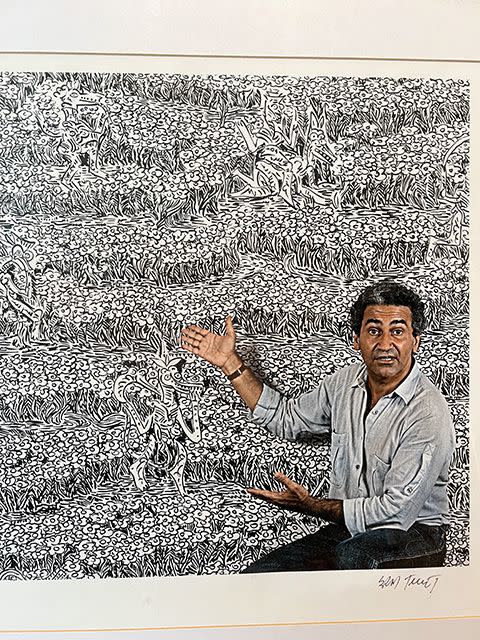

On the wall adjacent to the Maryan is a work by my father, George Chemeche. Composed of a series of repeating, interlocking birdlike creatures, it reminds me of an M.C. Escher drawing. In truth, they evoked the repetitive floral patterns one finds in Middle Eastern mosques. My father was born in Iraq in 1932.

As a child, I idolized my father, who was my primary influence in terms of art. Behind the front desk in the lobby was a door that led to my father’s art studio, the former ballroom of the Chelsea. Rumor had it the studio was Mark Rothko’s before it was my father’s.

I have fond memories of my father’s studio in the Chelsea Hotel, of stepping into an enormous white space covered in paint splatters, nails, and staples. In one of his ubiquitous blue denim shirts with the sleeves rolled up, a pipe clenched between his teeth, Dad would study a painting, determining whether it made the cut. If it didn’t, he’d procure a razor and slash the canvas. I used to think it was a way of stopping himself, ending the urge to edit and reedit a composition that just wasn’t working. I don’t think he knew why he did it. It was a compulsion, a violent urge. In the final years of his life, my father wondered if the Iraqi-Jewish diaspora, and the destruction of his culture that followed, had anything to do with it. He and his family fled Iraq in the 1940s. They lost their home, all of their possessions. When they arrived in Israel, they became second-class citizens. Members of the Ashkenazi majority called them slurs like shwarts. They lost their culture, their pride, and their identity too. Perhaps the trauma embedded within him the need to purge, to destroy and discard the artwork—and by extension pieces of himself that continued to be treated as a second-class citizen in the United States. My father was the opposite of a materialist.

But back to the hotel. As we traveled between our flat and his studio, he would analyze the art belonging to other artists. “Most of these are bad. Not serious,” he would say. “They just hang things in the hallways because they will never sell.” His words would later be echoed by many others, confirming that the majority of the pieces were, indeed, bad. Under his tutelage, I developed a specific eye for what “good” was. My father had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in the 1960s. The era of French bohemia had entered a twilight period of its own—by general consensus, it ended in the 1930s. Still, the likes of Joan Miró frequented the cafés, and Christo and Jeanne-Claude were my father’s contemporaries. Within this environment, his aesthetic was defined, favoring artists like Picasso, Georges Braque, and Chaïm Soutine. He liked bright colors, playful figures, abstracted forms, and thick, heavy daubs of oil paint that retained the energy of the artists’ gestures. I inherited this aesthetic, believing it to be the definition of taste as a child. It was only in my 20s that I began to understand: Taste, or a predilection for a certain style, is in many ways subjective.

By the late ’90s, my father could no longer sell his art. Ironically, given his earlier critiques, more and more of his own paintings appeared in the Chelsea, expanding up onto the first and fourth floors. By then, the lobby was painted canary yellow. A new piece by my father—a relief made of bent aluminum, paint, wood, and cloth—hung next to the front door.

On the first floor, a series of multicolored prints emulating stained-glass windows and featuring his muse, Aya Azrielant. On the fourth, a series of woodblock prints in black-and-white. There were 13 of his pieces in total. By the early 2000s, he’d quit painting altogether. He once told me his heartbreak over the attacks of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent Iraq War crippled his inspiration. He shifted his attention to art scholarship and dealership. But his dreams of being successful in the United States, of being an artist—which he’d aspired to as a little boy in Basra, even before he understood that “artist” was a career—never left him. For hours he sat in the windowless TV room of our apartment, hunched into a flaking easy chair. Old movies lit his face in dim flickers. His lips moved silently, his hand gesturing before him—was he painting a phantom canvas? Emphasizing his conversations with long-dead friends and family? Then he’d say, “I don’t know what happened.” My father reckoned that he had failed as an artist.

As I got to know more of the residents in the Chelsea, I witnessed their myriad attempts to succeed and survive. Some wanted to gain notoriety—commercial and financial success. Some were just trying to pay the rent, buy a meal, and clothe their children while living a bohemian lifestyle in the legendary hotel. And others—deemed eccentric or untouchable by the outside world—were trying to make a space to honestly express themselves. In one way or another, many of these artists experienced some sort of failure in their endeavors. Those who found success were the exception.

As I grew older, my conception of what constituted good art, bad art, failure, and success became more complicated. My eye shifted away from the dictates of good taste.

I had neither the skills to look through the eye of the past or an understanding of what was in vogue. So instead, these artworks became beloved artifacts. A family album. The shoebox you find in the attic, filled with snapshots of people who look like strangers but are vaguely related to you. The fading tintype of a long-dead great-great-great-aunt that creeps you out. The Polaroid picture of the cousin you hate—but still cherish cuz he’s blood.

From those who were talented, I learned that one could make good work and still fail to sell it. As for those who lacked ability, I began to cherish their attempts—their right to create, the beauty of their experiments with art. The care they put into trying. The care they put into hanging their works next to others on the walls. And I could not help but notice that, even if many of the paintings as individual pieces were poor (at times even unpleasant), together they formed a beautiful narrative, a collective curation that was painstakingly constructed over many decades.

The ability to try and fail is a privilege. Increasingly, it belongs to a select and wealthy few. In the past, the care evoked in the creation and hanging of “failed” art also represented a time when a wider spectrum of artists and eccentrics—superstars and failures, amateurs and masters—could afford to live in New York City. That time is past—the Chelsea Hotel is now a multimillion-dollar property, developed by real-estate speculators. A working artist could never afford to live there. With no space for the artists to survive to try and fail, we cannot possibly generate great creative work at the same rate as in the past.

In 2011, the Chelsea was sold and subsequently closed for renovations. The artwork, which was included in the sale, was put into a storage vault in Queens. Between 2011 and 2016, some artists reclaimed their paintings, while other works were allegedly lost or stolen from the storage space. By the time the hotel was bought by its current owner, Ira Drukier, and his partners, they were left with a diminished collection.

Now, the Chelsea Hotel’s transformation into a luxury five-star hotel is nearly finished. But since the collection has shrunk and there will be no new artist-residents to produce more work anytime soon, the management has opted to supplement the collection with new pieces.

The care that former artists took in trying evoked something special, some energy or history, in the older pieces. That energy is missing in the new works. Some are even mass-produced, printed in factories to be hung in hotel rooms, condos, and restaurants around the country.

Of the six George Chemeche paintings in the Chelsea’s collection, only one is on public display—the rest are in the rooms. It’s an Aya print in the eastern hallway of the 10th floor. I often visit it. I see the painting as a testimony to his time in the building and in America. In the arabesques and colors of the composition, I see the once-thriving city of Basra, the Shatt al Arab River that runs through it, the markets full of fresh fruits, spices, grains, and fish. All of that is gone now, because of the Iraq War.

My father died on January 11, 2022. With him went my last tie to my Iraqi-Jewish heritage. It’s a dwindling community whose history is increasingly obfuscated by the new narratives promoted by the Israeli state. I continue to live in the Chelsea Hotel, among the few artist-residents who remained after its sale.

Before the hotel’s closure, the halls were full of the sounds of actors, musicians, and playwrights making and rehearsing their work. Those sounds are gone, but the artwork remains. I still study the paintings. I continue to imagine the stories belonging to people who were here for the nearly 100 years when the Chelsea was a home to artists and outsiders alike who lived, tried, and beautifully failed.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports