The effort to honor a 94-year-old Negro Leagues umpire with a bronze statue

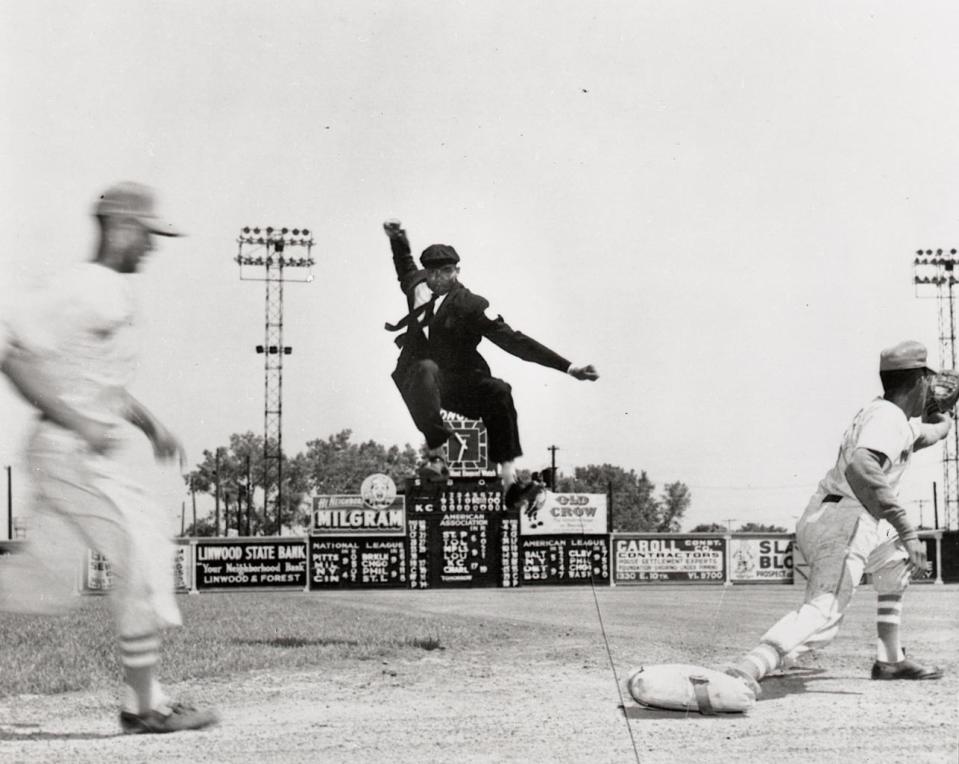

Look at the photograph. It’s perfect. The blur that is baseball wheedling its way into the frame on the left, the stirrups and spikeless shoes representing another era on the right, the Old Crow encouraging a nip of the stuff that burns going down and the smiling Milgram man saying hello because that’s what people did then. All of it is window-dressing for the man in the middle, his feet above the fence, his fist threatening the light tower, cheeks puffed and tie flapping and arms to the side, like rigor had overtaken them. He is what umpires today are taught not to be: the center of attention.

Bob Motley simply could not help himself. He was Superman in reverse. When he wore that black tie and black jacket, Motley transformed from the humble man who spent his days toiling at the GM plant, the war hero with a Purple Heart, the dedicated husband and father, into someone who owned his dominion. He spent nights around some of the greatest showmen sports ever knew, and he was the one who could fly.

That Motley turned the humble out call into a performance personified not only the man but the time and place in which he worked. The staid set of rules that govern baseball today did not exist in the Negro Leagues, where the game sought to fulfill one goal: entertain. Few boundaries encumbered them, and this stretched to the umpires, too. They were part of the show. Motley took this responsibility seriously enough that one time he almost saw the wrong end of a butcher’s knife on account of it, but then that’s a story for a little later.

Right now, there’s something important happening, the sort of thing that gets lost in the day-to-day. Motley, the last surviving umpire from the Negro Leagues, is 94 years old and starting to show signs of dementia. And before he goes, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, one of the true jewels of the sport, wants to add a 13th life-size bronze statue to its Field of Legends. Right behind Josh Gibson, near Satchel Paige, in the same vicinity as Cool Papa Bell, alongside Buck O’Neil would be Bob Motley, memorialized forever.

“So many of these coronations come when people are gone,” said Bob Kendrick, the executive director of the museum. “For us to have this unique opportunity to pay respect to Mr. Motley is something we’re all kind of excited about. We know it is a race against time. That the people you’re honoring, who made this history, all are going to be gone at some point in time. Each time you lose one, that window closes so much more. It does magnify why we document as much as we can, obtain as much as we can. So these men don’t fade off when they pass on.”

For years, Dick Davis dreamt of securing Motley’s legacy in a sculpture by the talented artist Kwan Wu. Davis was a longtime city councilman in Kansas City, and during an event at the museum, he and fellow councilman Jermaine Reed wondered why a field displaying the finest Negro League players couldn’t also include its most respected umpire.

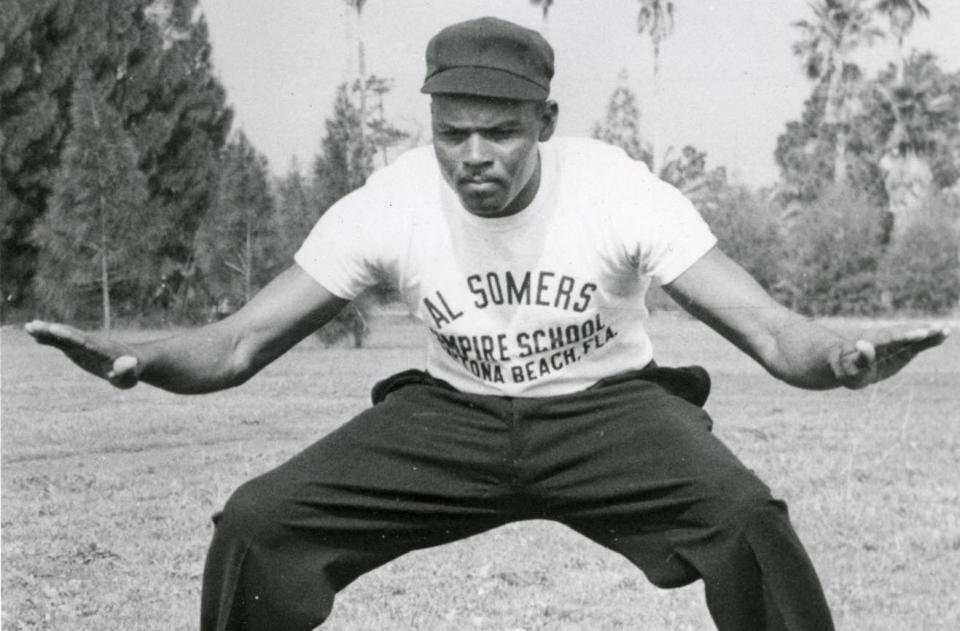

“He’s a great American,” Davis said, and that goes well beyond him serving as the first black umpire in the Pacific Coast League and first to attend the Al Somers umpiring school and first to serve as chief of umpires for the College World Series. It stretches all the way back to Jim Crow Alabama, where the foundation for Motley’s success blossomed amid searing racism.

When Motley was 4, his father died after drinking poisoned well water. His family believed the Ku Klux Klan or jealous neighbors were responsible. As a kid, he worked at the Jefferson Davis Hotel. When he saved enough money, he joined family in Ohio, even getting to play one game for the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League. He allowed a single, double, double, triple and home run and literally ran off the field before securing an out. Motley’s playing career ended that day.

Baseball was not done with him. Motley enlisted in the Marines in 1943 and joined the all-black regiment stationed at Montford Point in North Carolina. They were sent to Okinawa as part of the 52nd Infantry, and during a battle he was shot in the foot. Because he couldn’t play during his recovery, Motley instead umpired games on the base. When he returned home, Motley had settled in Kansas City and was calling local Ban Johnson games when a Negro Leagues umpire no-showed and Motley was deemed ready.

Soon, everybody knew him. On out calls, Motley leapt into the air like a guitarist in the middle of an inspiring riff. On safe calls, his did the splits before extending his arms. Motley could pull off the act because of his game’s substance. He was a great umpire and he knew it. Who else would run Buck O’Neil from a game?

Motley was at the heart of one of O’Neil’s favorite stories. As manager of the Kansas City Monarchs, he thought Motley had botched an infield-fly-rule call. O’Neil called him a “son of a bitch.” Nobody talked about Motley’s mama that way, and for the first and last time in his career, O’Neil was ejected. On the bus back to the hotel, Motley realized he had no hotel room for the night and, hangdog look on his face, asked O’Neil if he could shack up with him. They shared a bed that night.

“And I turned my back to that sucker!” O’Neil later cackled.

His issues with Motley never lasted long. One night, after a disputed call, Monarchs infielder Hank Baylis seethed at Motley, and on the bus ride back, Baylis brandished a long knife and threatened to kill Motley, who always brought his mask on the ride just in case a player tried to act a fool. O’Neil told Baylis to sit down, lest he end up off the Monarchs and in a jail cell.

If O’Neil saved Motley’s life, as Motley contends to this day, he returned the favor by venerating O’Neil’s. The Negro Leagues museum was a long-shot idea hatched out of a small room in Kansas City where a few people believed that the public would want to know more about this league of incredible talent and characters that lived in the shadows. In the early 1990s, when the museum was fledgling, Motley was among those who personally picked up the rent. Then Ken Burns’ documentary “Baseball” helped turn O’Neil into a star, and the interest in the Negro Leagues made Motley’s seedling of an idea a necessity.

It’s fitting, then, that the museum is planning on dedicating Motley’s statue in November at the celebration for what would’ve been O’Neil’s 106th birthday. After watching the Hall of Fame wait until after O’Neil’s death in 2006 to honor him with a lifetime achievement award in his name, Kendrick is understandably wary about waiting any longer. No, not all of the money is there yet – the museum has a GoFundMe page to supplement private donors – but this is too important to keep putting off.

Only 120 or so players from the Negro Leagues are alive still, and most played toward the end, when integration foretold the leagues’ demise. Willie Mays and Hank Aaron are among them, and both know what it’s like to play in a game called by Bob Motley.

It was a pleasure, a privilege, something that grows more special by the years, like that photograph. Look in the background and you’ll notice there isn’t any sign of other players. And it might just be the perspective, but look, too, at the angle from which the picture was made: super low, like the photographer knew Bob Motley was going to jump and wanted to make him look bigger than the world.

This perfect photograph may well be staged, though if it is, in no way does that lessen its perfection. In so many ways, Bob Motley was bigger than life, bigger than the strictures of his time, his game, his country. This may have been artistic license, but it was something more: a snapshot of history that gives a movement and a man the glory each so richly deserves.

More MLB coverage on Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports