Dying at work: How Arizona fails to protect workers on the job

Alex Quaresma and Rudy Mori were friends and co-workers. Alex had just gotten engaged and Rudy had only been working for the trench-digging company for four months.

They left home on a hot July morning.

They were on the last stage of a job, digging to find a sewer line in a 10-foot trench. It was supposed to have safety measures in place but it didn't. The trench collapsed and filled with dirt. Co-workers called for help and rushed to save them.

Alex and Rudy were buried alive.

The state agency that investigates workplace injuries and fatalities found Construction Specification Solutions, the company they worked for, had broken safety laws. The company − also known as Turnco − was fined a mere $8,000.

“It’s a slap on the wrist,” said Deanna Mori, Rudy’s younger sister.

Arizona’s worker-safety program is supposed to protect the welfare of 3 million employees.

But during departed Gov. Doug Ducey’s eight years in office, the Arizona Division of Occupational Safety and Health – known as ADOSH for short – has been more concerned with the growth and profitability of Arizona's companies than holding them accountable for safety violations.

The number of unannounced inspections and financial penalties plummeted.

The Arizona Republic spent more than a year examining the state’s worker-safety program. It attended hours of board meetings of the Industrial Commission of Arizona, the state agency that oversees health and safety in the workplace. It read thousands of pages of fatality and injury investigations, lawsuits and state and federal audits of the program. It spoke to workers, company owners, lawyers, safety experts and industry representatives.

Among the findings:

Arizona’s governor exerts a powerful influence over the regulatory board that oversees workplace safety. The governor hires the head of the Industrial Commission and appoints the five commissioners. The commissioners then appoint the ADOSH director, who hires inspectors and decides how many inspections to conduct.

When Ducey took office in 2015, ADOSH had 25 inspectors on its payroll. That number has dropped to as low as 14. Today, commissioners say the number is 15 and another 6 are being actively recruited. ADOSH has also hired eight technicians to help with inspections. The lack of staffing is the main reason that compliance inspections have fallen by 54% since 2014.

Fewer inspections have resulted in fewer financial penalties imposed on companies that break the law. In 2020, a total of $505,800 was collected, down markedly from $1.1 million in 2017.

The commission has the ability to raise revenues through an annual assessment on worker’s compensation premiums. It could use the money to beef up compliance staff. But instead of increasing revenues to hire staff, the commission slashed the assessment in 2018 and revenues have fallen.

The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration has repeatedly criticized Arizona for failing to impose adequate financial penalties on companies that break safety laws and for dragging its feet putting in place new federal safety standards. It got to the point where the feds in 2022 threatened to revoke the state’s ability to run its own safety program. “This lengthy series of shortcomings in the Arizona program demonstrates fundamental deficiencies,” OSHA wrote last year.

Meanwhile, the number of Arizona workers who have been injured or who died on the job climbed steadily during Ducey’s tenure. In 2020, there were 97 workplace deaths, up from 69 in 2015. Injuries at private employers have risen from 54,100 to 59,800 over the same period. When Ducey took office, the rate at which workers got hurt on the job was lower here than it was nationally. Between 2018 and 2020, however, the rate in Arizona grew to be significantly higher than the national average. Even in 2021, despite a slight decline in the rate, Arizona workers remained more likely to fall ill or get injured on the job than Americans in general. Arizona reported 67 fatalities in 2021, though the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that because of challenges obtaining key source documents for Arizona, “case counts may be underrepresented.”

69809769007

- Embed

- Not set

- Phoenix

- Not set

- 01/14/23 10:17:53 PM

- Not embargoed

embed:

Return to Asset Tab

SEO Warning

Layout Priority

69809762007

- Embed

- Not set

- Phoenix

- Not set

- 01/14/23 10:08:47 PM

- Not embargoed

embed:

Return to Asset Tab

SEO Warning

Layout Priority

Arizona is headed in the wrong direction by doing fewer inspections and giving companies fewer financial penalties, according to a safety expert.

“It’s basically a signal to the business community that health and safety compliance is not important,” said Peter Dooley, a Tucson-based certified industrial hygienist and safety professional who has studied ADOSH for more than a decade.

While the Industrial Commission acknowledges that inspections and penalties have dropped over the past eight years, it says those metrics don’t take into account the myriad ways in which ADOSH helps to make Arizona workplaces safer. The state has increased consultation visits with businesses from 300 to 1,200 a year and considers its engagement with business as more of a partnership than a policing function.

“We’re really proud of the positive impact that ADOSH has had for the state of Arizona and for every employer, every worker,” said James Ashley, who was appointed Industrial Commission director by Ducey in 2015, in a recent interview with The Republic.

Arizona’s economy boomed under Ducey thanks to his push for a pro-business regulatory environment. The state added more than a half-million private sector jobs during his tenure. But relations with OSHA have been tense.

As to the threatened federal takeover, the commission says that’s unfounded and arbitrary.

In a written response to the feds, the commission said it “strongly disagrees” that Arizona’s worker-safety plan is less effective than federal OSHA. It emphasizes that it takes a collaborative approach to safety that includes building partnerships and alliances with industry groups and companies.

Commission Chairman Dale Schultz said he has emphasized developing collaborative, cooperative programs with businesses and industry since being appointed a commissioner in 2015.

“To me, it's always a balance,” he told some of ADOSH’s newest employees at a recent meeting of the enforcement unit. “I have always enjoyed the role of being a consultant, rather than being the law.”

He said he doesn’t measure ADOSH’s success by fines or citations. He instead focuses on how collaborative partnerships with companies improve safety within the companies and industries.

Unlike OSHA, the commission has chosen not to publicize in news releases when things go terribly wrong. The result, however, is that some companies ignore safety laws because they don’t feel the pressure of being publicly outed. And ADOSH reports are riddled with horrific events that could have been prevented.

Take the man who died from bee stings and the nine others who were injured at a citrus farm near Yuma in 2019, after the employer didn’t check the field for hazards first.

Or the man who fell through a skylight and plummeted 40 feet to his death at a Goodyear construction site in 2017 because there was no proper safety protection in place.

Or the two men who died at a truck wash in Avondale in 2021 after breathing in a hazardous chemical, after the employer failed to provide training and did not assess for hazards.

The families they leave behind are devastated. Unlike a long illness where people have time to prepare, workplace fatalities happen suddenly. Families never expect their loved ones to walk out the door and not return.

Andreina Ramirez Cabrera was killed in June when the forklift the 25-year-old was driving before dawn tipped over and crushed her at a Tempe lumberyard. An ADOSH inspection found no evidence that the company violated safety laws.

But her sister, Stephanie Soto, is searching for answers of what went wrong. She wonders if the tragedy could have been prevented perhaps through better lighting.

“I don’t see the world the same anymore. It feels like something is missing, like it just doesn’t feel right,” Soto said.

Few requirements to be on worker-safety board

A few times a month, the Industrial Commission of Arizona gathers in a cavernous auditorium at commission headquarters in downtown Phoenix.

Outside the auditorium is a wall-size mural titled “The Spirit of Arizona,” depicting the state’s past, present and future with Arizona icons of cowboys, a saguaro and a hot-air balloon under a soaring rainbow.

The governor personally visited the Industrial Commission in June 2018 and was photographed with the commissioners, smiling in front of the mural. Ducey clutched a framed replica of the mural in his hands.

The commission is in charge of administering and enforcing workplace safety laws. But its public meetings draw few visitors. It’s mainly commissioners, staff and grim-faced officials from companies facing possible fines for safety violations. Their voices echo through the nearly empty room.

Under state law, the governor appoints the five commissioners who are confirmed by the Arizona Senate and serve staggered, five-year terms. The governor also appoints the director of the Industrial Commission, and commissioners hire the ADOSH director.

10065158002

View Live Edit image

- Image

- Cheryl Evans/The Republic

- Arizona Republic

- Not set

- 07/14/22 8:10:10 PM

- Not embargoed

image:

Return to Asset Tab

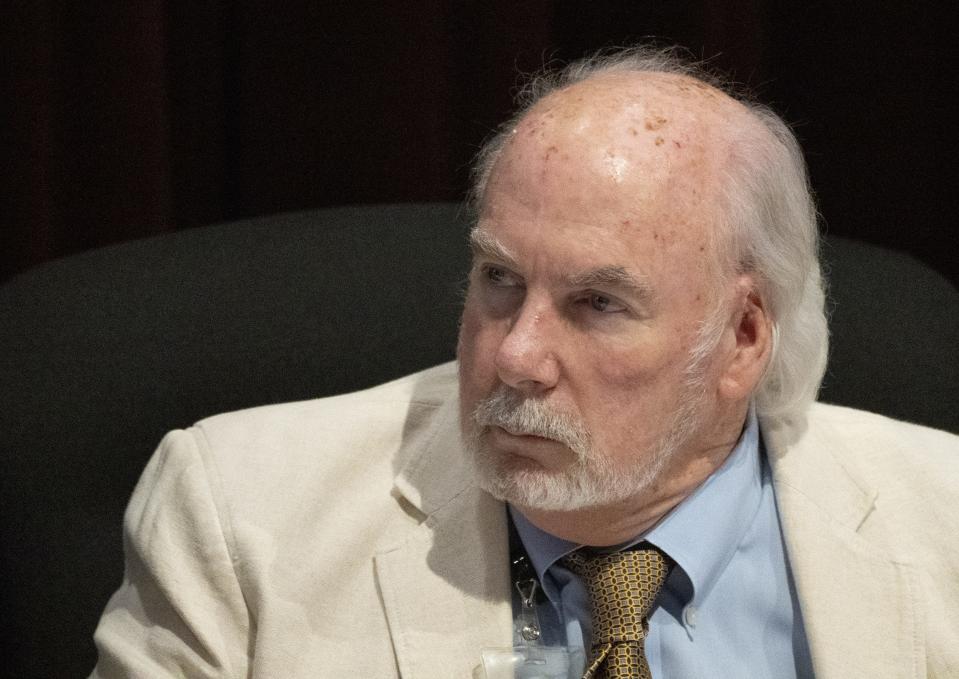

Industrial Commission of Arizona Chairman Dale Schultz attends a meeting in Phoenix on July 14, 2022.

SEO Warning

Layout Priority

There are few requirements on who can be a commissioner. They have to be Arizona residents for at least five years. No more than three can be from the same political party. There is no requirement that the commission include a representative from labor or union. Photos of past commissioners fill the wall of an upstairs conference room; they are nearly all men.

The current commission has three Republicans, one independent and one seat that has been vacant since 2021.

The current chairman, Dale Schultz, works as a risk manager for Valleywise Health, Maricopa County’s safety-net health system. His roots with the commission date back to the 1970s, when he served as an intern to the director.

An ethics expert interviewed by The Republic said political pressure could come into play because the governor appoints the Industrial Commission director, rather than commissioners hiring the person.

“It strikes me as unusual that the board doesn’t have their own authority to hire their executive and then hold that person accountable,” said John Pelissero, a senior scholar in government ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

Ducey’s office did not respond to an interview request and did not provide responses to a list of questions submitted by The Republic.

The new governor, Katie Hobbs, issued a statement saying workplace safety is a priority for her administration. "Every Arizonan deserves to go home safe from work at the end of the day,” she said.

The Industrial Commission director and the ADOSH director said they didn’t feel political pressure from the governor’s office to go easy on companies.

“Never,” ADOSH Director Jessie Atencio said. “My degree is in environmental, occupational health and stuff. … We’re firm and we’re fair. And we also make sure that if there's any education that we can provide, we provide that. But it doesn't absolve us of what we have to do.”

The commission has many duties. One key responsibility is to review fatality investigations conducted by ADOSH. When a worker dies on the job, ADOSH does a fatality investigation to find out what caused the death and whether the company violated safety laws.

ADOSH has jurisdiction over most private and public workplaces in Arizona. But other agencies handle fatality investigations for workers killed in mines or on Indian reservations or federal employees.

The commission can’t shut companies down. But it can give citations for safety violations and financial penalties.

The commission usually hears one or two fatality reports per meeting. The ADOSH director reads a summary of the fatality investigations and outlines any alleged safety violations that were found. Common violations include failing to train workers for the job they are doing and not ensuring they have or use safety equipment. It’s also common for workers to be killed or injured because companies fail to have safety procedures to prevent dangerous equipment – such as electric saws – from starting up unexpectedly.

At a November meeting, the commission heard about three fatalities: A worker was shocked to death when a repaired electrical cord came into contact with water at a Casa Grande tile manufacturer.

Another worker fell off a ladder at a home construction site in Gilbert and was impaled on rebar that wasn’t covered with a protective cap.

The third worker at a Phoenix company that builds wooden pallets lost his footing and fell backward into an electric saw that was in the process of being shut down. The saw should have had protective guards in place.

In meetings, the ADOSH director shares with the commission any alleged safety violations and proposes financial penalties. The commission can follow, modify or reject the recommendations.

Sometimes the family of a worker killed on the job will attend commission meetings to hear the results of the fatality investigation. They are often searching for answers about what happened to their loved one.

That’s what the families of Rudy Mori and Alex Quaresma did after the men died in a trench.

‘Cave in, your guys are buried’

Working in trenches wasn’t the first job choice for Quaresma or Mori. But it was hard to find work because they had served time in prison and had felony records.

Pipelayer was one of the jobs available.

They were part of a construction team that installed underground utilities for housing, often working as subcontractors to housing developers.

Mori was a buff guy, 6 feet tall and 204 pounds. His shaved head gave him an imposing look. But he liked cupcakes, sometimes polishing off a dozen at a time. He went by the nickname “Butch” to avoid confusion with his father, who was also named Rudy.

He was generous with his time. His three sisters said he would help wash dishes and take out the trash without being asked. He worked on his sister Jessica Mori’s house once for nine hours straight, removing the popcorn ceiling. He had a wife, Christie, and two stepchildren.

Quaresma moved to Arizona from California. He was divorced with two teenage children and was engaged. He met Tara Macon at a Walmart. She was on her way to her car when they saw each other, and their eyes locked. She kept moving.

“I don’t want to seem rude,” he told her. “But I’d love to exchange numbers.”

Impressed with his confidence, she agreed.

They lived a few blocks from each other, so it was easy to hang out every day. They both liked hiking, antiquing and eating at roadside diners. They took road trips, sometimes driving to Tucson just for dinner. Quaresma seemed to be trying to make up for the freedom he lost in prison.

Quaresma popped the question during a trip to Las Vegas in June 2020. Macon was surprised when the chocolate cake she ordered as dessert was brought out with an engagement ring on top. Then he got down on one knee and proposed.

Less than a month later – on July 23, 2020 – they got up as usual around 4 a.m. and kissed each other as he headed to work.

As was his habit, he sent her the location where he would be working that day, an upscale housing development near State Farm Stadium in the West Valley.

They spoke again by phone later that morning. Everything was fine. The crew was working in a series of trenches, trying to locate sewer pipes.

Trenches pose a hazardous work condition if the contractor does not use the recognized and accepted safety measures. A trench wall can collapse without warning, trapping and killing workers. There’s no time to react. A small amount of dirt may not seem dangerous. But a cubic yard of dirt can weigh as much as 3,000 pounds – the same as a small car. When a trench collapses, thousands of pounds of dirt can and will pin and normally kill the trapped worker.

When a worker is in a trench that is more than 5 feet deep, the contractor is required to make the trench a safe work area. The contractor has a few options: The sides of the trench that are more than 5 feet deep can be sloped or laid back or the trench can be shielded with a steel trench box.

The last trench that Quaresma and Mori entered that day had none of those safety features.

They were working in ground known in the industry as “Type C” soil, a sandy mixture that carries a greater risk of collapse than a soil classified as a “Type B” soil, which the foreman thought they were working in.

The foreman took a photo around 10:30 a.m., showing two men working in a deep trench without a protective system.

Quaresma and Mori were inside the trench as noon approached, using hand tools to dig for a sewer pipe. Suddenly, the walls collapsed. Soil poured in. Workers outside the trench called 911 and phoned the crew’s foreman who was not on site then.

“Cave in, your guys are buried,” one of the workers told him.

The Phoenix Fire Department arrived and saw co-workers trying to rescue the men. Fearing another collapse, they ordered them out of the trench. Quaresma was buried. They could see the top of Mori’s head.

More:Arizona's worker safety program puts workers at risk. Here are 7 ways to fix it

Fewer inspections, less enforcement

ADOSH had not inspected Construction Specification Solutions in at least the last three years. Most workplaces go years without an ADOSH inspection. The state doesn’t have many inspectors.

ADOSH on its website addresses why it doesn’t inspect more workplaces.

“In a word, resources,” it says. “A compliance officer can only conduct so many inspections during a given period. If we had more compliance officers, we could conduct more inspections and that would make everyone happy. OK, maybe not quite everyone.”

While no state has the money to inspect every workplace every year, Arizona’s inspection record is especially poor, according to the safety experts and federal audits.

The most recent “Death on the Job” report by the AFL-CIO found 17 states where the ratio of inspectors to employees is greater than one per 100,000. Arizona had the highest ratio at one inspector per 201,697 workers.

When asked about the ratio, the Industrial Commission in a statement said that number “seems to be dated.” The commission instead pointed to the state’s fatality and injury/illness rates, which consistently show “that Arizona is one of the safer states in the nation to work. As a matter of fact, Arizona has been one of the safest 20 states every year over the last five years when it comes to workplace fatalities.”

Federal audits have repeatedly faulted ADOSH for not doing more inspections. The compliance unit – which conducts unannounced inspections based on complaints and other factors – is chronically short-staffed. ADOSH has trouble filling and retaining inspectors.

A federal audit found that the number of compliance officers able to conduct independent inspections declined from 13 to five in 2021.

The short staffing means fewer inspections at Arizona workplaces and less enforcement of safety laws. ADOSH conducted 486 compliance inspections in fiscal 2021 – less than half of its goal for the year, according to a federal audit.

While ADOSH is doing fewer inspections, the agency has emphasized free consultation visits for workplaces. These are voluntary safety reviews requested by a company and scheduled in advance. ADOSH then prepares a report of any hazards that were found. Hazards must be fixed but don’t result in violations or financial penalties.

Ashley, the Industrial Commission director, said consultation visits are a proactive effort to prevent injuries. Under his leadership, consultation visits increased from about 300 to 1,200 a year.

But unlike inspections, consultation reports aren’t available for the public to review, according to the Industrial Commission. Not even if the same employer later has a workplace injury or fatality.

The Republic requested a copy of a consultation report for a company that had a consultation visit in March 2022 and had a workplace fatality three months later. The consultation report made recommendations for correcting hazards, according to a letter sent to the company from ADOSH. But the list of hazards or what the company did to fix them was not in the public file.

The Republic wanted to know whether the hazards identified as part of the consultation visit were related – or not related – to the workplace fatality that later occurred. The Republic argued that without the report, the public cannot evaluate the effectiveness of ADOSH oversight with voluntary inspections.

But ADOSH wrote that it was following federal policy designed to encourage workplaces to allow consultation visits. Making the report public would create a “chilling effect” on the consultation program, leading to an increase in unsafe working conditions, ADOSH wrote to The Republic.

Fewer inspections have meant fewer total fines against companies.

Money collected from financial penalties declined from $1.1 million in fiscal 2017 to $505,800 in fiscal 2020.

Even when a company is penalized, the fine is likely to be less than the national average. The average fine in Arizona for serious penalties for large companies was just $2,109 compared with the $6,575 national average, according to a recent federal audit.

Peter Dooley, the Tucson-based safety professional, has followed ADOSH’s activities for more than a decade. He calls Arizona a “lowball underachiever” when it comes to enforcing safety standards. He cites as one example what he calls ADOSH’s “deplorable” record of not doing much follow-up when workers complained that their employers weren’t providing them with protections – such as enough personal protective equipment – during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Workers were desperate for better protection, Dooley said. But ADOSH either lacked the capacity or the motivation to respond, he said.

The Republic reported on how ADOSH received more than 300 complaints about COVID-19 safety measures from March 2020 to March 2021 and issued citations related to the pandemic in only three cases.

The Republic’s analysis found that few workplaces were inspected, with ADOSH closing about seven of eight cases with no site visits, relying instead on employers that described their compliance efforts in letters to the agency.

Industrial Commission officials dispute criticism that the state is headed in the wrong direction. They say critics are not taking into account the agency’s broader safety program, which includes consultation visits, training and partnerships with companies and industry groups.

They say the decline in financial penalties happened because the agency hasn’t been able to fill all the inspector positions.

To try to fill gaps, ADOSH and some other states have created a new position called “technician” for applicants who may not have been eligible for jobs as inspectors in the past. The new position includes people with degrees in chemistry or biology, which are fields conducive to working with health and safety standards, ADOSH officials said.

Eight technicians had been hired so far since August, though as of late December none were far enough along in training to conduct independent inspections.

‘I do not wish this upon anyone’

Deanna Mori, Rudy Mori's younger sister, was in the middle of an appointment when calls flooded her cellphone.

“Something happened to your brother,” her mother told her through tears. “We think he passed away at work.”

On this day – July 23, 2020 – the trench he worked in collapsed shortly before noon, burying 33-year-old Rudy Mori and his co-worker and friend, 36-year-old Alex Quaresma, under tons of dirt.

Their families rushed to the construction site at a new housing development in the West Valley. Police cars and fire trucks filled the area, cordoned off with yellow tape. They couldn’t find out whether their loved ones were still alive.

A couple of tearful co-workers approached. They were sorry, they said. They couldn’t get them out.

Tara Macon got a call about Quaresma from his mother. She rushed to the work site. All she knew was there had been an accident. She saw Quaresma’s co-workers hugging. She asked what was happening. An emergency worker told her it was now a “recovery” mission.

She wasn’t sure what that meant.

“We’re trying to recover their bodies,” the worker told her.

On the other side of the construction site, Rudy Mori’s family clung to each other as they learned the tragic news. His wife, three sisters, parents and other relatives decided to wait in the near-triple-digit temperatures for the bodies to be recovered. A company working in the area lent the family a canopy for shade, a cooler full of water and chairs.

An inspector with ADOSH, the state’s worker-safety program, arrived to interview witnesses and investigate whether safety laws were broken.

The family waited for hours in anger, shock and disbelief.

It was a complicated recovery. Phoenix Fire Capt. Rob McDade told the media that rescue workers had to take precautions to avoid the trench collapsing further while they recovered the bodies.

Rescue workers recovered the men’s bodies long after dark. The Mori family was still there.

A medical examiner later ruled their deaths accidental, the result of suffocation and smothering. Mori’s family clung to the hope that cuts the medical examiner found on his scalp may have meant he lost consciousness before he died.

OSHA officials said last year they were seeing an “alarming rise” in trench deaths around the country. OSHA stepped up enforcement after 22 workers died in trench-related accidents in only the first six months of last year. That was more than the 15 who died in all the previous year.

"Every one of these tragedies could have been prevented had employers complied with OSHA standards," Assistant Secretary for OSHA Doug Parker said in a statement issued in June.

OSHA said it was directing inspectors to make more than 1,000 trench inspections as part of increased safety measures. OSHA also encouraged states like Arizona – that run their own worker-safety programs with permission from OSHA – to consider additional safety measures, including criminal referrals to prosecutors for trench-related incidents.

In Arizona, ADOSH inspectors have the authority to stop and inspect if they see an unprotected trench. Since 2015, there have been seven trench fatalities in Arizona. During that time, ADOSH has conducted 393 trench inspections and, of those, 106 were the result of safety complaints.

ADOSH officials said the agency has not referred a work-related trench fatality to the Arizona Attorney General’s Office for possible criminal prosecution in recent memory. But that remains an option if warranted.

An ADOSH investigation into Mori and Quaresma’s 2020 deaths led to safety violations and financial penalties against Construction Specification Solutions, the company the men worked for.

The ADOSH report concluded the incident could have been avoided if the employer had taken safety measures such as installing a metal protective system or sloping the soil back to prevent a cave-in. The report also stated the company did not properly train workers on excavation hazards and safety precautions.

The crew’s foreman told ADOSH he was not on site when the trench collapsed. He said he had been in the trench when it was about 7 feet deep without a protective system and felt it was safe as long as someone was above, keeping an eye on workers below.

“We certainly think this is a tragic situation, send condolences for the family,” said Travis Vance, an attorney who spoke on behalf of the company when the Industrial Commission discussed the fatalities in early 2021. “First and foremost, we want to keep everybody safe.”

He said the crew’s foreman told workers to stop digging and went to get them drinks because it was a hot July day. The foreman was not there when the cave-in happened. He was not on site when the trench was as deep as the final measurements, he said. Vance told commissioners it was possible the ADOSH trench measurements were made after more dirt had been removed in the recovery mission.

“Our position would be that there would be no knowledge on behalf of the company of the conditions that have been cited,” he said.

Construction Specification Solutions, in a written response to ADOSH, said it conducted companywide retraining in trench safety and a group safety discussion within a few days of the incident. The foreman also completed a 30-hour OSHA course. The company and Vance did not return calls from The Republic seeking comment.John Wittwer, an attorney who currently represents the company, said the company won’t have any comment because of ongoing litigation.

J. David Gardner, a civil engineer expert with Robson Forensic, examined the ADOSH report at the request of The Republic. He said, in his opinion, the accident was easily preventable.

“All indications are that the contractor blatantly disregarded the recognized and accepted industry safety standards and regulations associated with trench work,” he said.

ADOSH determined that Construction Specification Solutions committed four “serious” violations. ADOSH said the company did not properly train employees and failed to install a protective safety system in the trench.

The proposed fine was $20,000. But under a formula allowed by federal OSHA, Construction Specification Solutions was eligible for a discount.

Because it had 18 employees, it was deemed to be a small company and its discount was set at 60%.

The fine was therefore reduced to $8,000.

“I don’t know,” Commissioner Joseph Hennelly Jr. said during the public meeting. “This whole thing seems light to me.”

He said the lack of safety systems on the trench was “a terrible oversight. That’s being kind.”

In the end, though, the commission’s vote was unanimous. Construction Specification Solutions was fined $8,000 with the discount.

Dave Wells, research director for the Grand Canyon Institute, a nonprofit think tank based in Phoenix who has studied ADOSH, called the $8,000 fine “appallingly small.”

“Two men died. That’s really disturbing. That’s a significant safety violation that led to their deaths,” he said.

A similar trench accident in Missouri killed one worker in 2022 and resulted in four serious citations issued to the company, similar to Arizona. That company was fined much more: $58,008.

The disparity is not lost on the families of the Arizona men.

“It’s a slap in the face,” said Macon, who was engaged to Quaresma.

“He loved his job. He believed in the company, and he was there whenever they needed him to be and his life was gone because of it. And they get a discount.”

When asked about the disparity between Arizona and Missouri, ADOSH officials told The Republic they would have to study the Missouri case to see what factors were used to decide the steeper fines. Each fatality case is unique, they said. Fines are based on several factors, including whether the company has a history of safety violations.

OSHA: Arizona has ‘history of shortcomings’

Arizona is one of 22 states that has permission from OSHA to run their own worker-safety programs for the private sector, state and local government workers.

OSHA audits the programs, and state's safety protections must be “at least as effective” as federal ones. OSHA says Arizona has a “history of shortcomings” in this regard. As a result, OSHA last year threatened to strip Arizona of its ability to oversee workplace safety.

Arizona’s program “has routinely failed to maintain its commitment to provide a program that is at least as effective as the Federal OSHA program in providing employee safety and health protection at covered workplaces,” the federal notice said.

Among the examples OSHA gave:

OSHA accused Arizona of repeatedly failing to adopt safety standards and directives in a timely manner. For example, it took Arizona more than six years to raise its maximum financial penalties to match federal ones.

Arizona ran afoul of OSHA in 2012 when its state standards to protect construction workers from falls didn’t match federal ones. OSHA required safety protection at 5 feet while Arizona only required it at 15 feet. A state law was eventually passed in 2014 to match federal standards.

The Industrial Commission in 2021 failed to adopt OSHA’s emergency temporary COVID-19 standards for health care workers. The standards dealt with personal protective equipment and other safety measures. It also would have given health care workers paid sick time if they contracted the virus.

Ducey called the threatened federal takeover “nothing short of a political stunt and desperate power grab.”

The Industrial Commission responded to the threat with a 51-page letter to OSHA filled with strident language. The commission accused OSHA of relying on inaccurate data and using “ill-defined” and “ever-shifting” standards to evaluate whether Arizona’s program was as effective as OSHA’s.

“OSHA continues to advocate a theory that State Plans must rubber stamp everything OSHA does,” the commission wrote.

The Industrial Commission blamed delays in adopting federal standards on having to change state laws – something that is outside the regulatory board’s authority. The commission also suggested the threat of a takeover was retaliation for the commission not adopting the COVID-19 standards for health care workers.

Arizona’s business community lined up to oppose a federal takeover of the worker-safety program. The companies writing support letters to OSHA are among the state’s most influential business and industry groups, including Arizona Public Service, Salt River Project, several chambers of commerce and construction and housing associations.

Unions and safety advocates generally supported the federal takeover.

The public comment period on the possible federal takeover has since closed. OSHA did not respond to calls and emails from The Republic, requesting an update. The Industrial Commission’s director said in a December interview with The Republic that he was optimistic that the outcome would be favorable to Arizona.

“We have a strong expectation this is going to be successfully, officially resolved very soon,” Ashley said.

‘It’s like a slow suffering’

Two years later, the families of the Arizona men killed in the trench grieve and remember their loved ones.

Tara Macon keeps Alex Quaresma’s car in the garage. She rarely drives his red Cadillac Eldorado but cannot part with it.

Joanna Noriega, one of Rudy Mori’s sisters, cannot bear to look at construction sites. Workers are building a new apartment complex near her job. Looking at the dirt mounds triggers bad memories.

“It’s like a slow suffering we’re all dealing with,” she said.

His older sister, Jessica Mori, avoids driving on Camelback Road. The name reminds her of the Camelback Ranch development where her brother died.

His sisters formed a text-message group with Macon. They send each other encouraging messages. It’s how they get through the tough days.

The family considered suing the homebuilder at the construction site and the subcontractor Rudy Mori worked for. But attorneys told them they didn’t have much of a case. Ironically, worker’s compensation laws provide companies with broad legal protection.

Quaresma’s mother is suing the homebuilder and related entities for negligence. They have denied the allegations.

Ducey left office in early January after two terms. Arizona’s new administration is faced with a choice: Continue on the same path or take federal threats seriously and reform the state’s worker-safety program.

Lawmakers will get a chance to weigh in soon.

The Industrial Commission is due for a state audit and legislative review this year. It’s part of the review process for regulatory boards called Sunset Review, where lawmakers look at the purposes and functions to decide whether to continue, revise or terminate the boards.

That outside review can’t happen soon enough for the Mori family. And they hope for substantive change. They would like an overhaul of Arizona’s worker-safety program: new commissioners, more inspections and higher financial penalties for companies who break the law.

10997710002

View Live Edit image

- Image

- Joe Rondone/The Republic

- Arizona Republic

- Not set

- 01/05/23 3:54:53 PM

- Not embargoed

image:

Return to Asset Tab

Deanna Mori shows a tattoo of the last thing she texted her brother, Rudy Mori, before his death. The text said, "just ...thank you." She was thanking him for running errands with her.

SEO Warning

Layout Priority

Deanna Mori keeps a photo of her brother in her living room. It was taken a few years before he died. Another picture on the refrigerator shows him snuggling and smiling with her 3-year-old son, Rome.

Rome is now 5, and he often begins his day by looking up at the photo and saying “good morning” to his uncle.

“I speak for my whole family, that I do not wish this upon anyone,” she said. “I do not want anyone else’s family to go through this.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: ADOSH under Gov. Ducey failed to protect Arizona workers: Here's how

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports