The Dodgers have retired Fernando Valenzuela's number. Does he have a path to Cooperstown?

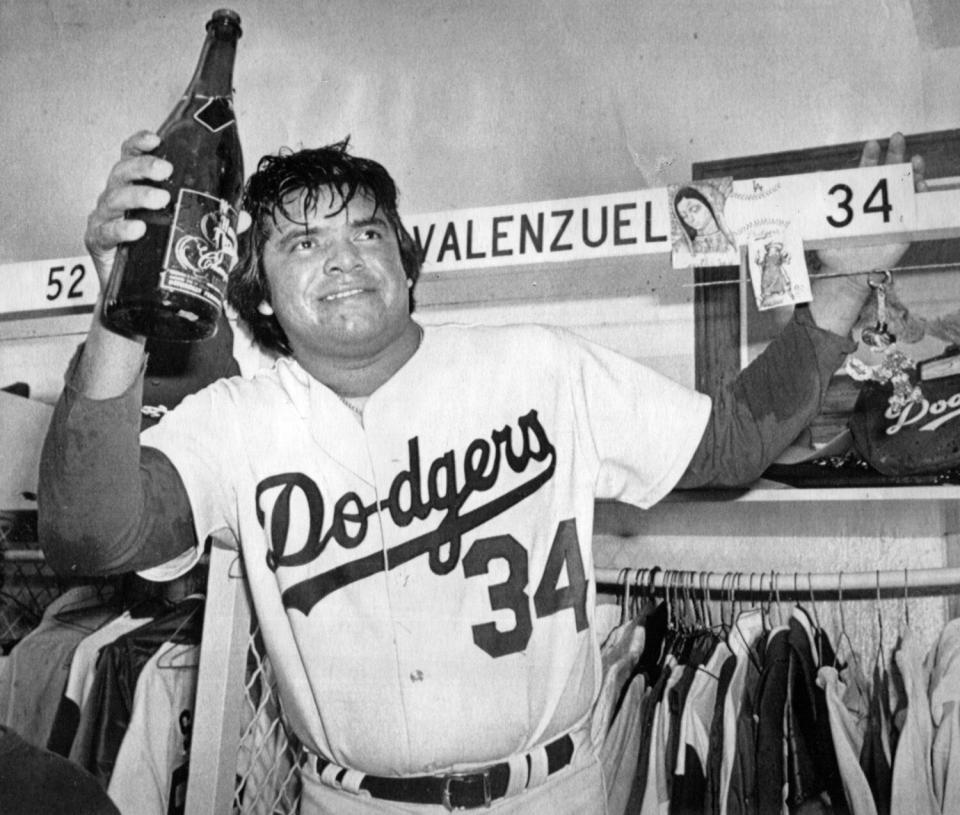

For the Dodgers, the No. 34 has long belonged to Fernando Valenzuela — and only Fernando Valenzuela.

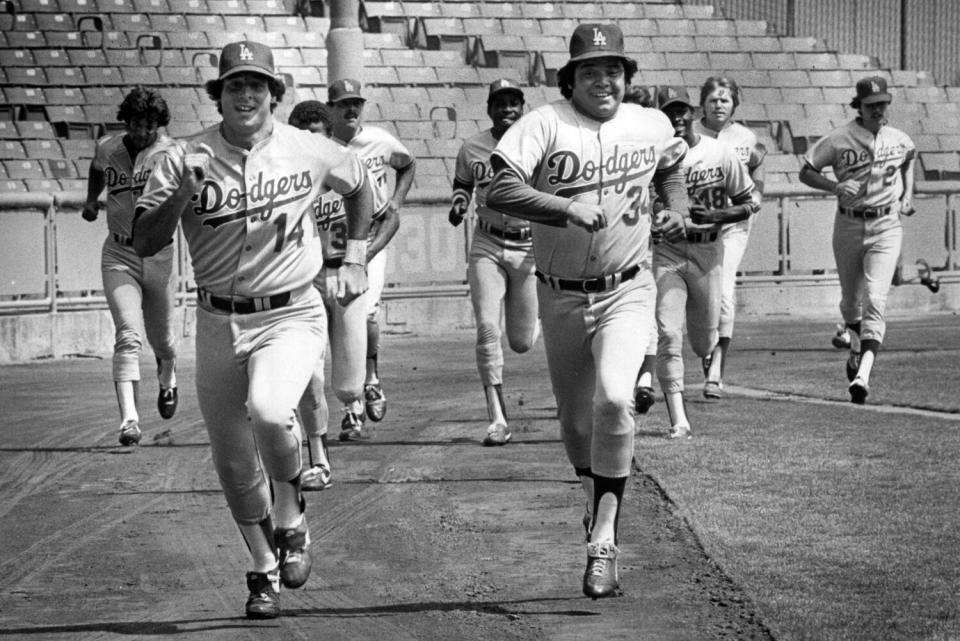

Consider that the Dodgers haven’t issued the No. 34 to a player since Valenzuela was unceremoniously released in March 1991. Consider that, 32 years later, his No. 34 jersey remains one of the most popular at Dodger Stadium. The unyielding connection illustrates Valenzuela’s deep impact on the organization and the region. Fernandomania is an indelible chapter in the city’s history.

Officially, however, the Dodgers wouldn't retire No. 34. The franchise’s rationale was straightforward: We retire a player’s number only if he is inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame after spending most of his career with the club.

That changed Friday when the Dodgers finally bent their rule for Valenzuela and retired his number during a pregame ceremony at Dodger Stadium. The portly left-hander from Sonora joined Jim Gilliam as the only people to have their numbers retired without induction into the Hall of Fame.

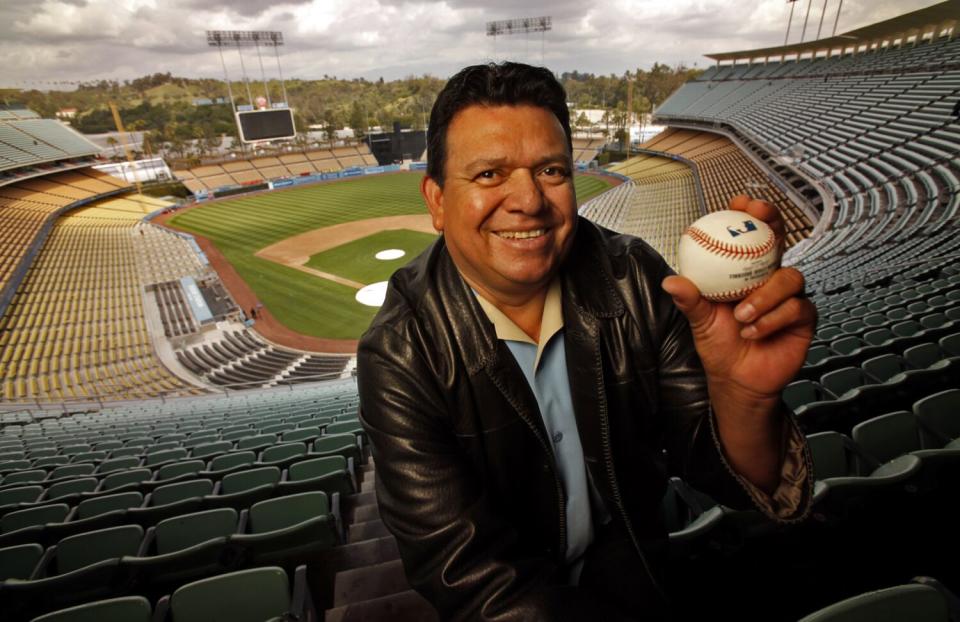

Although Friday’s event ended a persistent debate about the 62-year-old Valenzuela’s place in Dodgers history, it raises another familiar question: Is Valenzuela a Hall of Famer?

The argument for Valenzuela isn’t based on numbers; his statistics leave him short of the established threshold for a Hall of Fame starting pitcher. Instead, it’s based on emotional, unquantifiable reasoning; the idea that Valenzuela galvanized and expanded a fan base in the country’s second-biggest market, spread Major League Baseball’s influence in Mexico, and remains a cultural icon on both sides of the border.

Valenzuela didn’t come close to Hall of Fame induction when initially eligible for consideration. The Mexican left-hander first appeared on the ballot in 2003. He netted 6.2% of the vote, surpassing the 5% threshold to remain in consideration for another year. But the number dropped to 3.8% — a total of 19 votes — in 2004 and he fell off the ballot, rendering his chances for induction remote. To this day, no Mexican-born player has been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Jaime Jarrín’s mind often wanders into the what-if when asked about Valenzuela’s Hall of Fame candidacy.

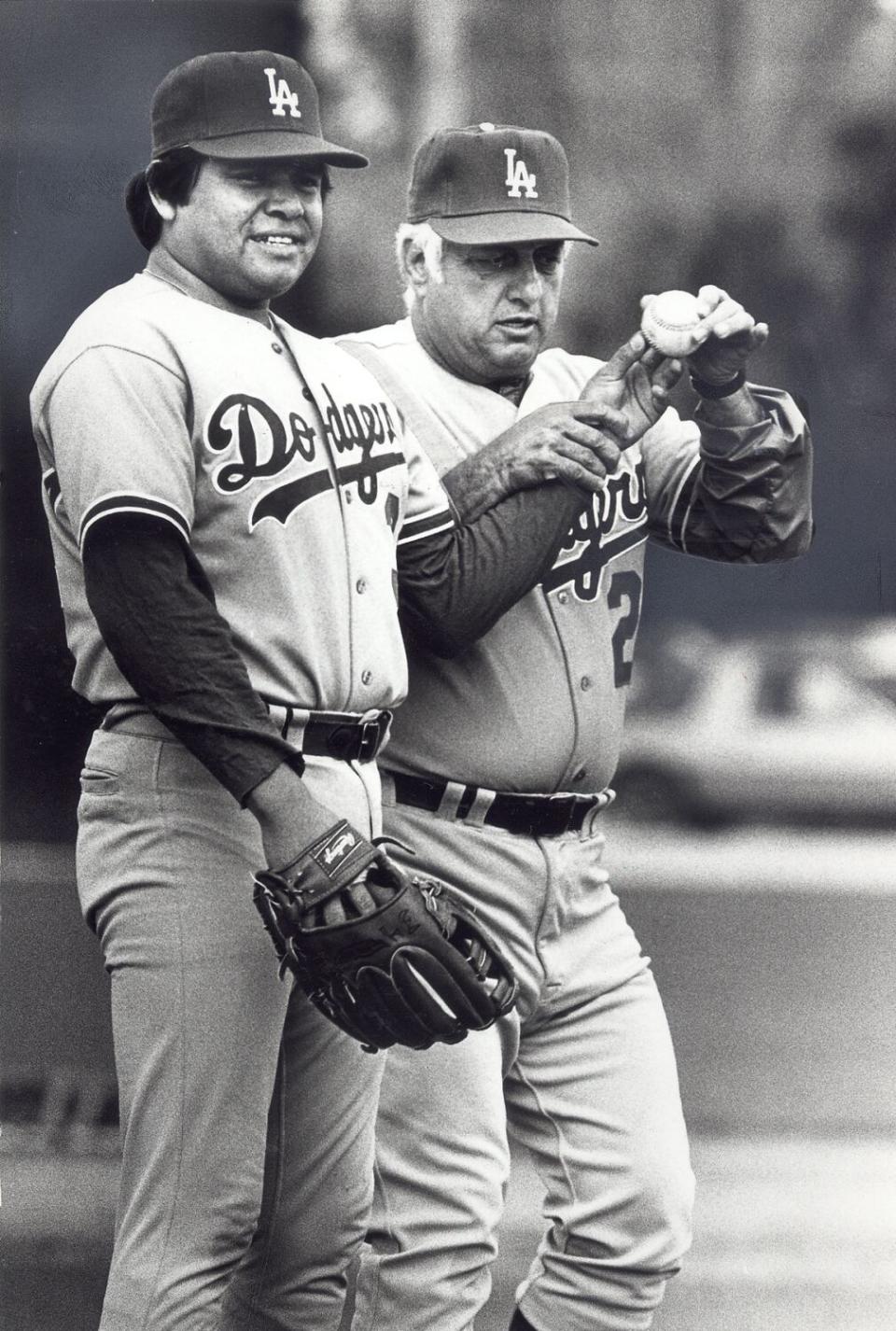

What if Tommy Lasorda didn’t overuse him all those years, pushing him to average more than 255 innings, throw 96 complete games, and lead the league in batters faced three times over his first full seven seasons? What if Valenzuela relented and chose to have surgery to repair his injured shoulder after all that work when he was still in his early 30s? How different would the star's career have gone?

“If he had gotten the surgery, he would've pitched more, he would've won more and he would've sealed his Hall of Fame case,” Jarrín, the Dodgers' former longtime Spanish-language radio broadcaster, said in Spanish. “But I think Fernando should be in the Hall of Fame because even though his numbers aren't extraordinary and he didn't pitch a lot of years, what he did for baseball no other player has done.”

The only current avenue to induction for Valenzuela is through the Hall of Fame’s Contemporary Baseball Era Players Committee. Every three years, eight players who played the majority of their careers 1980 and later are chosen by an 11-person historic overview committee to appear on a ballot. Players then must receive 12 votes from a 16-person selection committee for election.

In December, first baseman Fred McGriff was unanimously chosen through the process. Valenzuela, who declined to comment for this story, has never appeared on the ballot. The next round is slated for December 2025.

(The Contemporary Baseball Era Players Committee is one of three era committees the Hall of Fame cycles through annually. The others are the Contemporary Baseball Era Non-Players Committee — for managers, umpires and executives who made their contributions after 1980 — and the Classic Baseball Era Committee — for figures who contributed to the sport before 1980.)

Read more: Fernandomania: Documentary series examines Fernando Valenzuela's impact on the Dodgers

Another option to exhibit Valenzuela’s impact in the museum is the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award. The honor, established in 2007, is given to a person who “broadened the game’s appeal” with “character, integrity and dignity” comparable to the late O’Neil, a longtime Negro Leagues player and the first African American coach in MLB history.

“An important thing for fans to recognize is that the Hall of Fame and Museum is more than just a plaque gallery,” Hall of Fame President Josh Rawitch said. “It's also a three-story museum that has all sorts of exhibits and Fernando's contributions are significantly mentioned in our Viva Baseball exhibit and other areas where we talk about the Dodgers of the 1980s.

“For any player where the debate kind of rages on, whether they belong or not, I think it's important that people recognize that whether or not you're in the plaque gallery, we are documenting their history in the game and Fernando's always going to be a huge part of that.”

According to Rawitch, the museum is currently displaying various artifacts relating to Valenzuela, from two of his bobbleheads to a box of Corn Flakes featuring him on the cover to a baseball from his no-hitter in 1990 — his final season as a Dodger. It’s impossible to tell baseball’s history without Valenzuela.

But players have long not been inducted in the Hall of Fame for their impact — or fame — over performance. Perhaps the most notable example to the contrary is Candy Cummings, who pitched six seasons in the 1870s and is widely credited with inventing the curveball. He was posthumously inducted in 1939.

Valenzuela was on a Hall of Fame trajectory through his first six seasons. He was named Rookie of the Year and the Cy Young Award winner while being a key figure in the Dodgers winning the World Series in 1981. He finished in the top five for Cy Young three other seasons. He made the All-Star team each year, won two Silver Slugger Awards, and earned a Gold Glove. He tallied 97 wins with a 2.97 ERA and 84 complete games across 200 starts — and never landed on the injured list.

He won a career-high 21 games with a 3.14 ERA across 269⅓ innings in 1986 while leading the majors with 20 complete games. He was just 25 years old, but he never again regained that form.

He recorded a 4.23 ERA over the rest of his career. He completed just three full MLB seasons after the Dodgers let him go days before opening day in 1991. Ultimately, Valenzuela won 173 games with a 3.54 ERA in his 17 seasons. He finished with a career WAR of 41.3. By comparison, the average WAR for starting pitchers in the Hall of Fame is 73.3 — though conventional wisdom is a WAR of 60 or above warrants serious consideration for enshrinement.

Jarrín was Valenzuela’s interpreter when he burst onto the scene as a chubby, unknown rookie in 1981. Decades later he was Valenzuela’s partner on the Dodgers’ Spanish-language radio broadcast. In between, he was inducted into the Hall of Fame as the 1998 Ford C. Frick Award Winner. He lived through the influence Valenzuela had on Mexicans in Southern California.

“This guy came in, 19 years old, without speaking English, gordito, Indigenous features, long hair,” Jarrín said in Spanish. “He was the protagonist for not one game, not one week, but the whole year. A spectacular year. You don't have an idea how it was when Fernando pitched.

Read more: Arellano: The Gospel of Fernandomania: Fernando Valenzuela remains a Mexican American icon

“It was always sold out. At the Dodger Stadium entrance, you'd see vendors selling everything. Stamps, cards with photos of Fernando. Tacos. Everything at all the stadium entrances. Everything he did for baseball. He created more fans than any other player. Above all, people who didn't care about baseball before. People who didn't care about baseball began watching because of him.”

Across the border, Julio Urías, born in Sinaloa one year before Valenzuela threw his final pitch in 1997, saw Valenzuela’s impact through his family. Valenzuela, Urías said, was one of the three megastars during the golden era of Mexican sports, alongside boxer Julio César Chavez and soccer player Hugo Sánchez. His father, his grandfather, his uncles — the people who taught him baseball — all idolized Valenzuela.

“For them, he’s the God of baseball in Mexico,” Urías said in Spanish.

Valenzuela resonated, Urías explained, partly because he was just a guy from a rancho too. He made the dream of reaching the majors — of pitching at Dodger Stadium — seem attainable. A quarter-century after Valenzuela’s release, Urías arrived in Los Angeles as a hyped prospect not just for his talent. He, too, was a Mexican left-hander. He, too, was signed by scout Mike Brito. He was seen as the next Valenzuela. But he knows there won’t be another Valenzuela because Valenzuela was much more than a pitcher.

“He always has that standing because of what he did, what he lived, from where he came from, and how he accomplished it,” Urías said in Spanish.

Urías was there Friday when Valenzuela finally saw his No. 34 alongside other franchise greats. It took longer than expected, but Valenzuela’s place in Los Angeles is solidified. Time will tell if it changes in Cooperstown.

Read more: Hernández: Fernando Valenzuela's lasting impact on baseball makes him worthy of Hall of Fame

Sign up for more Dodgers news with Dodgers Dugout. Delivered at the start of each series.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports