Despite difficult ending, Jim Leyland’s Marlins tenure propelled him into the Hall of Fame

As a minor-league catcher with the Detroit Tigers in the 1960s, Jim Leyland could have never imagined sitting in Cooperstown, New York. The longtime baseball manager spent seven seasons in the minors and had a paltry .222 batting average before hanging up the cleats.

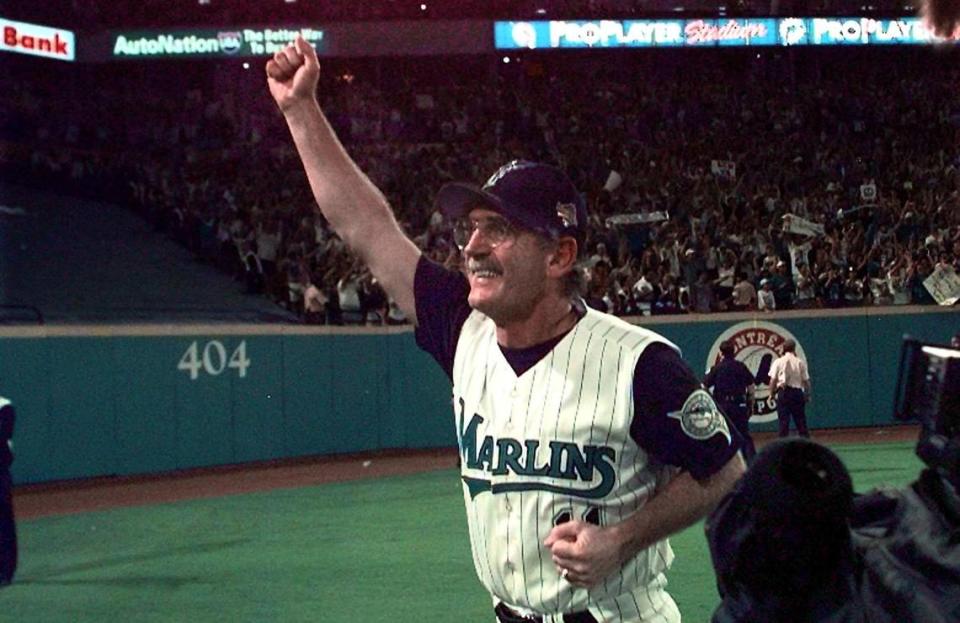

While Leyland’s dreams playing on the diamond might not have been realized, the 79-year old was able to leave his indelible mark on baseball in another way. With a managing career spanning four teams in 22 seasons, Leyland brought eight of his teams to the playoffs and won a World Series in 1997 with the Florida Marlins. Now, 54 years after he retired as a player, Leyland will be forever immortalized in baseball history, as he will be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on July 21.

“I’m a very realistic person. I realize the Hall of Fame is for players, and I’m going in as a manager. That’s different,” Leyland said. “I always put the players first, and I kind of feel like I’m a tagalong.”

Despite a short two-year tenure with the Florida Marlins, Leyland left a lasting legacy in South Florida, leading the Marlins franchise its first World Series championship.

“That year in 1997, we went into the season thinking we had a chance [to win it all]. We were 26-5 in spring training, and I was scared to death,” Leyland said. “These people think we’re gonna walk through this thing.”

“[I] had come close in Pittsburgh to getting [to the World Series], but we had never quite got there,” Leyland said. “I knew how tough it was to get that accomplished.”

With a lineup that included Moises Alou, Gary Sheffield and Bobby Bonilla, the Marlins pulled out a seven-game series against the then-Cleveland Indians to become MLB champions.

“I don’t think there’s any question that [the 1997 World Series] helped my cause to get to the Hall of Fame,” Leyland said. “If we hadn’t won it, I probably would not have gotten in.”

The team’s success was short-lived, as ownership forced the front office to trade many key players after the 1997 season. But Leyland seems to have long moved past it.

“Everybody knows the sale of the team and all that, and that’s all part of it, that’s fine,” Leyland said. “But, you know, winning a World Series, there’s no greater experience than that.”

Baseball has evolved throughout Leyland’s time in the major leagues. Changes in defensive alignments, pitching and batting styles have led to a league that looks dissimilar from the time Leyland started managing.

“I think the two biggest changes recently in the game are pitch usage and the way managers use their infield,” Leyland said. “They’re playing the infield much more and much earlier than they did in the early days. The pitch usage has confused hitters. 2-0, 3-1, 3-2 used to be a fastball count all the time, but [now] it’s no longer a fastball count.”

While the longtime manager has certainly found himself in tense situations before, it doesn’t lessen his anxiety about his upcoming speech in Cooperstown.

“[I feel] anxious [and] humbled,” Leyland said. “[I am] a little nervous about the speech. A lot of the hall of farmers’ [speeches] are emotional. I’m an emotional guy so I’ll try to keep that to a minimum.”

“I just want to make sure that I talk to the fans, I talk to the Hall of Famers and talk to everyone that’s watching on MLB Network,” Leyland said.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports