Can the NHL have 'super teams' like Golden State? (Trending Topics)

While millions across the U.S. were celebrating the nation’s independence from Britain, the Golden State Warriors declared their independence from the traditional rules of sport.

In signing Kevin Durant to a relatively team-friendly deal, the Warriors made themselves not only the heaviest favorite to win an NBA title we’ve probably ever seen, but created a regular team that could probably give an All-Star team assembled from the league’s other clubs a run for its money most nights.

Durant is maybe the second- or third-best player alive, depending upon your feelings about LeBron James and Russ Westbrook, and he joined the team with the best player, which already set the NBA record for wins in a season and lit a number of other individual and team records on fire. (Pity about that Game 7 in the Finals, though, ha ha ha.) If the Warriors lose more than four or five games out of their 82 next year, it will legitimately be considered a disappointment.

Now, without getting into the politics of sports take-ism in general — Durant is getting killed for taking less money to chase titles, but if he’d signed elsewhere for more money he’d get killed for being selfish instead — this has kick-started a debate about whether so-called “super teams” are good for the NBA or sports in general.

Personally, I found watching last year’s Golden State club beat the absolute hell out of the dregs of the league to be pretty fun. Steph Curry casually lobbing up half-court 3s and getting back on defense before they even went in was a joy.

But the heel turn in the postseason — and specifically the Finals Game 6 when Curry got thrown out for tossing his mouth-guard into the stands — effectively turned the Warriors into the nWo, and while it was great to see WCW get one over on the bad guys in Game 7, it’s also going to be fun as hell to watch the Dubs spray paint yellow stripes down battered opponents’ backs. And a big part of the nWo mystique was that anyone could be turned to their side at any time. Durant is effectively their Lex Luger. Russell Westbrook alone might not even qualify as Sting.

The Westbrook signing set off a lot of people in sports media, and that included some in the hockey world who wondered if a “super team” might be possible in the NHL. As in most other sports, people seem to want parity rather than one team just splashing more than 1,000 3-pointers on hapless opponents, dominating them to a perverse extent.

And in a staid sport like hockey, where Jimmy Vesey is still getting crap from Nashville about exercising a collectively bargained option to test free agency, it’s no surprise that one recent poll of more than 1,000 fans prefer to see everyone be kinda good than anyone be historically good. (And isn’t that so weird, given the fetishizing this sport does of the Edmonton or Islanders of the 1980s, or even Chicago today?)

Would you rather the NHL have "super teams" or parity?

— NHL Explainers (@NHLExplainers) July 4, 2016

For a lot of reasons, those anti-fun fans are likely to get their wish forever, thanks to the league’s various rules, intricacies and quirks.

The biggest thing to understand about basketball and why it’s possible for one or two players to take a mediocre team to the top of the league pretty much by themselves (see: Kevin Garnett and Ray Allen joining Paul Pierce in Boston, LeBron James and Chris Bosh joining Dwyane Wade in Miami, LeBron James and Kevin Love joining Kyrie Irving in Cleveland, etc.) is that the best players play at least 75 percent of the game. In hockey, the absolute busiest players usually don’t come all that close to playing half of it.

That alone is a huge reason why not even the single greatest hockey player would ever have the immediate value that even a top-15 NBA player does on a team. Sidney Crosby could join the Red Wings tomorrow and that team would still struggle to make the playoffs. Durant could have joined the Knicks, one of the worst teams in the league for years now, and they’d have been playoff-competitive right away.

There are a number of WAR-type stats in the NBA, and which is best depends on what you want to know, honestly. But let’s keep it simple and go by estimated wins added: Curry led the league (no surprise) by adding somewhere between 27 and 28 wins to the Warriors’ total in comparison with what a replacement player would have produced in the same minutes.

By comparison, the WAR stat for the NHL developed by the nice people at the now-departed and aptly WAR on Ice showed that over an average 82-game season from 2012-15, the most valuable player in the league in terms of wins added (Joe Pavelski) only tacked on an extra 5.3 or so W’s — 10-plus points a season. Now, a player that good is obviously quite valuable. Adding 10 points to a team total when the best clubs only produce about 110 is impressive. But it pales in comparison with Curry’s impact.

For that reason, even if an NHL team could somehow get a large number of the best players in the league assembled on one team, the amount better it would make them than the second- or third-best team in the league is a lot more marginal. Right now, the difference between the Warriors and the second-best team in the NBA was already somewhat big. Now it is ludicrously so.

Moreover, it’s worth noting here that the only reason the NBA is able to have super teams like this is that the NBA’s revenues are growing at a phenomenal rate, faster than it could have predicted when the last CBA negotiations were underway. As such, the TV revenues alone exploded and allowed Golden State the cap space to sign Durant in the first place. (And please, don’t ask me to explain how the salary cap in the NBA works; it’s a nightmare.)

The NHL, obviously, is in no such situation. TV revenues are flat and — thanks to the devaluing of the Canadian dollar — really kind of losing ground. Gate revenues are more or less maxed-out, unless it’s decided that we have to sit through two or three more outdoor games every year. The sport certainly isn’t growing globally in the way basketball is. So the odds that the salary cap just goes up, say, $15 million next summer and allows Pittsburgh to add, say, Brent Burns and Jamie Benn (both UFAs next summer!) are effectively non-existent.

And again, even if they did add Burns and Benn to a group that already includes Crosby, Evgeni Malkin, Phil Kessel and Kris Letang, the impact those two players have probably adds about seven or eight wins at the absolute most to the total they would have had anyway. That still has them losing probably a quarter of their games, and they’d be among the most talented teams assembled.

Hockey is weird like that. Because of the parity Gary Bettman and Co. have unceasingly pushed for years, the very best teams in the league and the very worst can play each other 100 times and the best one would still probably drop about 30 games. If the Warriors (with Durant) play the 76ers — a team tanking so blatantly the last few seasons it puts the Sabres of two years ago to shame — 100 times, it would be absolutely astonishing to see them lose five times.

In theory, if you could put together a team of eight high-end guys in hockey — say, four forwards, three defensemen, and a goalie, each of them a perennial All-Star — and fill the other half of your roster with replacement-level veterans and guys on ELCs, you would obviously destroy a lot of teams.

That’s probably about 60 percent of the game where you have an elite player on the ice, and if you spread them through the lineup, you probably approach 100 percent. Forget it at that point. But that’s impossible under the salary cap as we know it today, and will continue to know it for years to come: You can have, at most, four or five very good players. The Penguins are freakish in that they had Crosby, Malkin, Kessel, and Letang all at once. Those are four of the four or five best players at their positions, and they still needed plenty of help from a rookie goaltender, journeymen, and even some recent AHLers to get past San Jose.

The Warriors are in an entirely different stratosphere. Even if they take Durant and Draymond Green off the floor, they still have Curry and Klay Thompson in. And so on. That’s usually going to be enough to get you through even a fairly competitive game with little difficulty. When they deployed their small-ball quintet of Curry, Thompson, Green, Andre Iguodala, and Harrison Barnes in crucial situations last year, they lived up to the “Death Lineup” billing. Teams had no answer for them, big or small. Adding Durant to that mix in Barnes’s place takes it from Death Lineup to Nuked-From-Orbit Lineup.

Meanwhile, Travis Yost recently called a forward group of Malkin, Crosby, and [anyone else] Pittsburgh’s version of the Death Lineup. Adding Kessel to that duo, for example, pushed the Penguins’ possession and expected-goals percentages into the neighborhood of 70 percent or more. Of course, they only played about 21 minutes together at 5-on-5 this year, which is weird on the surface. But they neither scored in those 21 minutes, nor were they scored upon, so there was no great impetus to keep them together. Especially because Crosby-with-anybody is typically going to net you goals-for percentages north of 60.

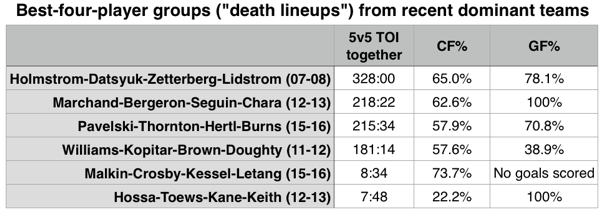

Here’s some data from Puckalytics of recent “Death Lineups” I could think of that used at least four top-level players together at the same time:

(And just to clarify: Yeah, given the TOI, you can probably guess that Chicago Death Lineup scored one goal to its opponents’ none. But Boston’s outscored opponents 14-0 in more than 218 minutes. Good lord!)

No one would deny that groups like this are extremely good and fun to watch when they play together a lot, no matter what your affiliation with the team they play for may be. Seeing the best players together for long stretches of time — none of this “Keith, Toews, Kane, and Hossa were together for 7:49 in an entire season” trash — is in the best interests of not only the teams when they need a goal, but also potentially the entire sport.

You see an awful lot of Steph Curry jerseys (but hopefully not so much the sneakers) and Warriors gear just about everywhere. It’s almost like the NBA knows how to promote its stars and put them in a position to succeed as much as possible!

Regardless, these are players better used throughout the lineup than together, because that’s how hockey works. Even being ultra-dominant for 23 minutes a night leaves 37 in which you are vulnerable. With Durant in the fold, there’s basically not going to be a minute for the Warriors all season in which at least one top-20 player isn’t on the court. And even that minute would probably be due to either injury or Steve Kerr figuring, “We’re up 40 at the end of the third, so let’s just rest everybody.”

Imagine, then, an NHL super team that regularly rolled a death lineup (say, two lines and two pairings) in close third periods. The brutality with which they would cruise through hapless barely-made-the-playoffs clubs in the early rounds would give way to watching them whale on the depth players of actual quality teams as their inevitable Cup win approached.

And it would be something to behold. Finally our generation would have something to hold up to the legendary teams of the past.

Again, it’s never going to happen.

But it would be great if it did.

Ryan Lambert is a Puck Daddy columnist. His email is here and his Twitter is here.

All stats via Corsica unless otherwise stated.