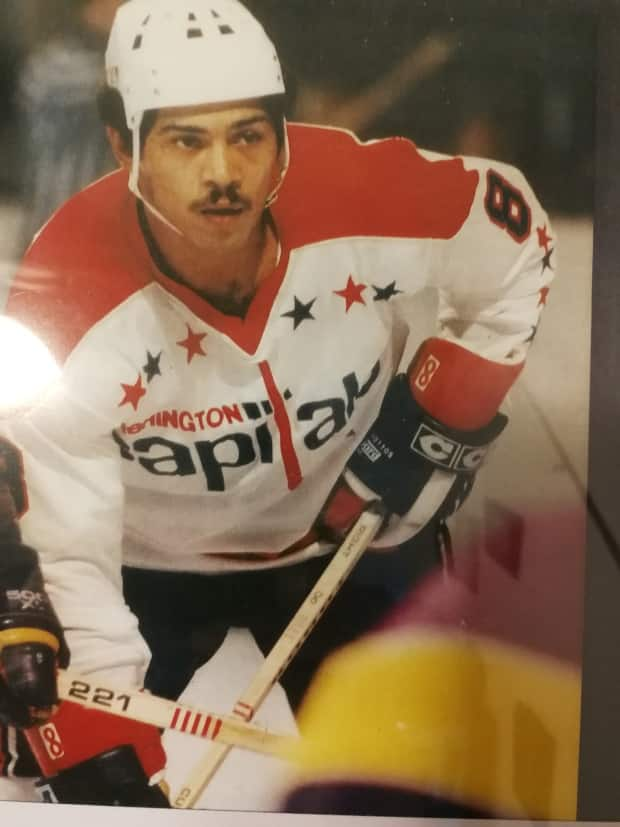

Bill Riley, 3rd Black player in NHL history, was 1st Black player for the Winnipeg Jets

(Submitted by Tracey Riley-O'Hearn - image credit)

Bill Riley, the first Black player in Winnipeg Jets history, remembers his time playing in Winnipeg as too short.

"My time in Winnipeg, I really, really enjoyed it — and my teammates were great to me," Riley told CBC News.

In 1974, Riley became the third black player to play in the NHL when he was called up to play with the Washington Capitals. He played with the Caps for four seasons and, in 1976-77, he became the first player in team history to finish a season with a positive plus-minus — a ratio that tracks how often a player's team scores and is scored on while they are on the ice.

In 1979, four teams from the World Hockey Association merged with the NHL: the Edmonton Oilers, Quebec Nordiques, New England Whalers — now Carolina Hurricanes — and Winnipeg Jets.

The Jets selected Riley in the ensuing expansion draft. But earning his spot on the roster in the 1979-80 season was another issue.

"I played professional [hockey] for 10 years, and never had a better training camp than I had in Winnipeg Jets training camp," he said.

"Clearly, without a doubt, deserved to be signed to a contract. But that wasn't to be."

Riley spent 63 games with the Nova Scotia Voyageurs of the American Hockey League in 1979-80, but suited up for the Jets 14 times. He scored three goals and dished out two assists as a Jet.

He didn't suit up for Winnipeg after that season, but Riley remembers Winnipeggers treating him well. He especially remembers being invited to a Ukrainian dance, where he was introduced to cabbage rolls and perogies.

Racism 'rampant' in minor leagues

Though he was called up to play with the Capitals and Jets through five seasons, Riley spent many games playing minor hockey in Dayton, Ohio, Hershey, Pa., and Atlantic Canada from 1974-75 to 1983-84.

"[Racism] was rampant," he said. "But it just motivated me."

He first crossed the Canada-United States border in British Columbia on his way to Dayton. Riley says the border guard on the American side was nasty enough to make him question whether he wanted to pursue a hockey career in the U.S.

"In Dayton, Ohio, I was treated like a king. I did not experience any racism whatsoever," Riley said.

That changed on the road, though. When the team visited in-state rivals in Columbus and Toledo, Riley says he "should have been wearing earplugs, because I was called names I didn't even know what they meant."

The names came from the opposing players, he said. But fans would join in too. In Toledo, the organist would play a racist song and fans would belt it out.

"But my teammates, to the number, were all on my side," he said. "Lots of times, when I went to fight, they pushed me out of the way and they'd take care of it."

At times, players would storm the stands and start brawls, he added.

The first game in Toledo, three players from the opposing team, including their tough guy, picked fights with Riley simply because he was Black. Riley won each fight, but after the game he contemplated discussing his future with the team with his coach, he said.

At practice the next morning, his coach pulled him aside and said every team in the league was trying to trade for Riley because of his fighting the game before.

"You went from nobody knowing you to everybody knowing you," Riley recalls his former coach saying.

Diversity in today's NHL

Although more Black hockey players have suited up for NHL clubs, such as P.K. Subban and ex-Jet Evander Kane, a criticism against hockey in general continues to be that it is a sport played by mostly privileged white people.

The death of George Floyd renewed an urgency in the civil rights movement last spring, and professional athletes and sports leagues used their platforms to organize and rally. But the NHL was the last major sports league to issue a statement about Black Lives Matter — and only did so after players called for it.

"What took them [so long]? Why did the players have to do it? Why didn't the NHL brass step up to the plate like the other three major sports? That's what bothered me," said Riley, who was disappointed by the NHL's inaction.

He also questions why diversifying hockey rests solely on the shoulders of Willie O'Ree, who broke the NHL colour barrier in 1958 and is now a Hockey Hall of Famer and the NHL's diversity ambassador.

"The National Hockey League has never reached out to me or Mike [Marson, the second Black NHL player]," said Riley. "We have stories to tell."

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports