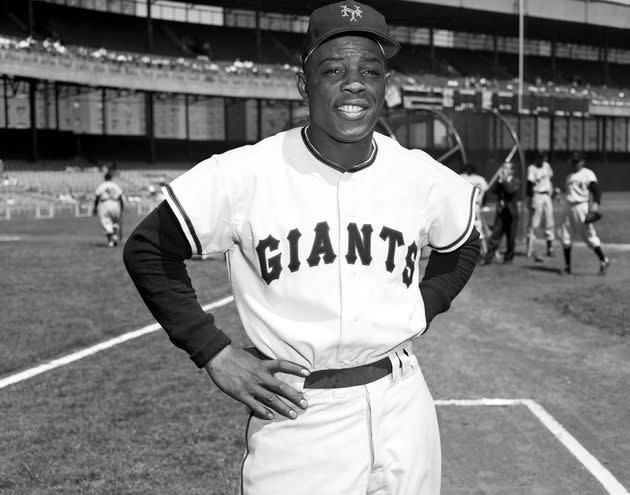

Baseball Legend Willie Mays Is Dead At 93

Willie Mays, a Hall of Fame baseball player known to fans as the “Say Hey Kid,” diedTuesday at age 93.

“My father has passed away peacefully and among loved ones,” his son, Michael Mays, said in a statement released by the San Francisco Giants. “I want to thank you all from the bottom of my broken heart for the unwavering love you have shown him over the years. You have been his life’s blood.”

Mays played center field in the MLB from 1951 to 1973 for the New York Giants, the San Francisco Giants and the New York Mets. He hit 660 home runs and won one World Series during his 22 seasons.

Tributes quickly poured in from other members of the Giants family.

“I have no words to describe what you mean to me,” Barry Bonds, another Giants player recognized as one of the sport’s all-time greatest, posted on social media in a tribute to Mays. “[Y]ou helped shape me to be who I am today.”

“I fell in love with baseball because of Willie, plain and simple,” Giants president and CEO Larry Baer said in a statement.

In 1951, he was the National League’s Rookie of the Year, exploding onto the scene just four years after Jackie Robinson famously broke baseball’s color barrier on the Brooklyn Dodgers, helping usher in a new era in the MLB. Mays’ excellence played its part in helping desegregate the league, exposing fans, reporters and decision-makers to the wealth of baseball talent that had been relegated to the Negro Leagues.

The entirety of Mays’ career presents an argument that he was the greatest all-around baseball player ever. On top of 660 home runs, Mays collected 3,293 hits, 338 stolen bases, two National League MVPs and one batting title. His 7,095 outfield putouts prevails as an MLB all-time record, and when paired with his 12 Gold Gloves, Mays’ statistical resume shows he was a genuine five-tool player. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979.

He was fast on his feet, powerful and accurate with the bat, and strong when cocking the ball back above his head, ready to throw down any runner. Longevity was perhaps his greatest asset, as Mays went to the All-Star Game 24 consecutive times from 1954 to 1973 — a streak so remarkable that fellow Hall of Famer Ted Williams once remarked, “They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays.”

His grace, strength and athleticism on the field made him a wonder to watch.

And that’s how Mays got his first experience in professional baseball — by watching it. Born to Cat Mays, a Negro League player, and Annie Satterwhite, a standout track and basketball star in high school, Mays grew up with baseball. As a 10-year-old, Mays watched his father from the bench of games, but soon, the roles were reversed. He signed his first professional contract in 1947 at age 16 with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos, a minor league affiliate of the Negro Leagues, and by 1948, he was on the Negro Leagues’ Birmingham Black Barons.

Over the next two years, Mays’ profile rose, and scores of MLB scouts came to Black Barons games to see Mays and to present contract overtures. The Boston Braves were the first to contact Mays — nearly securing an outfield pairing of Mays and former all-time home run leader Hank Aaron — but he ultimately signed with the New York Giants in 1950.

At first, things didn’t go so well. Mays went hitless in his first 12 MLB at-bats, but on lucky No. 13, he smacked a home run off the left field roof of the Polo Grounds against legendary pitcher Warren Spahn.

Mays won the National League MVP award at age 23 after missing two years to serve in the Korean War. Those two years prevented him from beating Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record of 714, but provided him with the bulk to become a power-hitter.

“[Being in the army is] why I got strong. I think I could’ve hit maybe another 50 or 60 home runs,” Mays said.

Although he quickly became a star, Mays grew to prominence in a racist era. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he did not often speak about civil rights issues, for which he was criticized by Jackie Robinson. In his 1964 book, “Baseball Has Done It,” Robinson filleted Mays for avoiding race-related controversy and not being the crusading Black icon Robinson wanted him to be.

“I hope Willie hasn’t forgotten his shotgun house in Birmingham’s slums, wind whistling through its clapboards, as he sits in his $85,000 mansion in San Francisco’s fashionable Forest Hills,” Robinson wrote.

Knowing that Robinson was an activist at heart and he wasn’t, Mays was not bitter about Robinson’s comments. He felt comfortable with himself and chose to represent his race as the archetypal role model. Mays didn’t drink, smoke or scandalize, embedding himself within American pop culture as a dedicated professional who worked hard for what he wanted. As MLB’s highest paid player in the mid-1960s, he often donated to children’s causes.

Overall, his success helped lift Black men in his sport. Mays was part of the first MLB African American outfield, flanked by fellow Giants Hank Thompson and Monte Irvin.

In his later years, Mays remained a staple in the Giants clubhouse, often appearing at games and team ceremonies and serving as a mentor to players. In 2017, the MLB renamed its World Series Most Valuable Player award after him.

When President Barack Obama awarded the Medal of Freedom to Mays in November 2015, Obama said, “It’s because of giants like Willie that someone like me could even think about running for president.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated incorrectly that Willie Mays had 3,283 hits. He had 3,293.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports