How to afford raising a world-class athlete

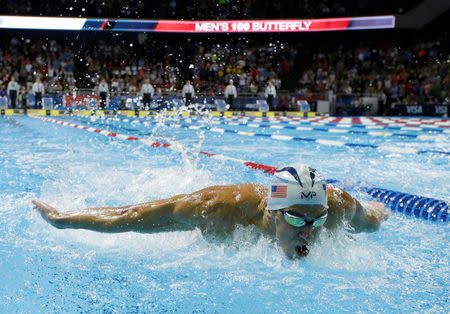

By Chris Taylor NEW YORK(Reuters) - When the Summer Olympics begin in Rio on Aug. 5, you will see 10,000 of the world's best athletes compete, and a much smaller number of them being draped with medals. But who really deserves gold? The families who scrimped and saved to get them there. Raising a world-class athlete under your own roof can easily gobble up your life and your bank account. For Barbara Hopewell of Palm Desert, California, raising famed Olympic swimmer Summer Sanders meant driving to lessons at 4:25 a.m., enabling elite coaching, and getting her to swim meets around the country. At the time, Hopewell was a single mom who toggled between being a flight attendant, selling real estate and working at a Budget Rent-a-Car. "It was not cheap," says Hopewell. "I was spending at least $400 a month on her team dues, suits, caps, goggles, swim meets, hotels, meals on the road. It was definitely a strain." Hopewell remembers a month where she had to juggle three major national swim meets, including the Olympic trials and the NCAA championships. She had little choice but to take the whole month off work, without pay, and cover all travel expenses herself. This year's U.S. delegation to Rio includes 555 athletes across 27 different sports, and that means there are 555 families across the country who have scrimped, saved, and sacrificed for years to make these dreams happen. The price tag for raising an artistic gymnast comes to around $15,000 every year, according to one estimate by Forbes Magazine. Other disciplines can be even pricier, like fencing ($20,000 annually), table tennis ($20,000) and archery ($25,000). "The financial struggle is very real for many families," says Melissa Brennan, a Dallas financial planner and mother of a competitive gymnast, who trains at a gym that has produced multiple Olympians. Of course, no proud parent wants to deny their uniquely gifted child a chance at a gold medal. So how can families make the finances work, without raiding retirement funds and going bankrupt in the process? Some tips from the experts: BE PART OF THE 'SHARING ECONOMY' Long before companies like Uber (http://uber.com) and Airbnb (http://airbnb.com) started taking over the world, parents of budding sports stars knew all about the "sharing economy." That is because they had little choice but to pool resources, in order to shave costs. "Car pools are great, and shared lodging at swim meets helps out a lot," says Hopewell. ENJOY THE COLLEGE CASH Until they go professional, athletes are hamstrung in their ability to secure money from sources like endorsement deals. But top-level athletes do have one juicy source of indirect funding: A college scholarship. Total NCAA Division I and II scholarships amount to around $2.7 billion a year to 150,000 student athletes, according to college-aid expert Mark Kantrowitz. CROWDFUND THE COMPETITIONS The average Olympian makes a paltry $20,000 a year. That is why the emergence of crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe (http://gofundme.com), RallyMe (https://www.rallyme.com/) and Sportfunder (http://sportfunder.com/) have been godsends for amateur athletes. A number of current U.S. Olympians went the crowdfunding route to help finance their journeys to Rio, including wrestler Kyle Snyder, decathlete Jeremy Taiwo and fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad. PLAN AHEAD With many sports there is an off-season, when competitions are few and costs are lower. During those down times, it is critical to continue to earmark some cash in a special account, otherwise the in-season fees will pack a wallop, says Brennan. NO POT OF GOLD AT THE END OF THE RAINBOW It is natural for parents to hope they might one day be reimbursed for expenses, once the endorsement deals start rolling in. But remember these are not NFL or NBA athletes, says Ed Butowsky, managing partner with Chapwood Investments in Addison, Texas, and a money manager for many professional athletes. These are Olympians, and apart from the occasional Wheaties box, there are not a ton of lucrative endorsement deals to be had. "There is no way around it: You are going to spend a lot of money," Butowsky says. "And at the end of the day, you don't even know if there is going to be a gold medal - or any gold at all." (Editing by Bernadette Baum)

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports