The 2016 NBA draft class had a historically awful debut, but it's not doomed

Ask any NBA fan — maybe not a casual fan, but certainly an informed one — what the best draft class ever is, and you’ll likely get one of two answers: 1996 or 2003. The former featured Kobe Bryant, Ray Allen, Steve Nash and Allen Iverson. The latter was headlined by LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, Chris Bosh and Carmelo Anthony.

On the other side of the coin, the 2000 draft is generally considered among the worst ever. The first draft of this millennium produced only three All-Stars — No. 1 overall pick Kenyon Martin, No. 19 pick Jamaal Magloire, and second-round pick Michael Redd, all of whom made a single All-Star appearance — and ranks at the bottom of all drafts in essentially every metric. The signs of trouble were present early on: The group posted a paltry 32.2 win shares in its rookie year. At that point, no draft class had ever posted a mark that low.

Then came the 2014 class, which posted an even more anemic collective win share total of 21.1, thanks in part to major injuries to multiple players. Unlike the 2000 class, though, not nearly enough time has passed to pass full judgement on this collection of players. While the 2014 draftees posted another two less-than-inspiring campaigns following their debut, it’d be irresponsible to group them with their Class of 2000 counterparts at this early stage.

This past year’s crop, the 2016 class, posted another historically bad number, just slightly beating out the class two years before it. Led by Rookie of the Year Malcolm Brogdon of the Milwaukee Bucks — the first second-round ROY since 1966 — this group only compiled 26.5 win shares.

The question, then: How strongly does rookie year performance correlate to career performance? And, in turn: Are this year’s sophomores doomed?

Using data from previous draft classes, we have the ability to see just that. First, though, it’s important to know what win shares are.

A win share is a “statistic which attempts to divvy up credit for team success to the individuals on the team” first created by stats whiz Bill James, according to Basketball Reference. It involves a lot of complicated math, but essentially it seeks to measure how many of a team’s wins can be attributed to the contributions of a single player and thus, roughly, how much of an impact any given player makes during his time on the floor.

The 1989 draft was the first to feature only two rounds, the same number used today. As we’ll discuss later, though, going back to 1987 provides a better template for how the 2016 class can bounce back.

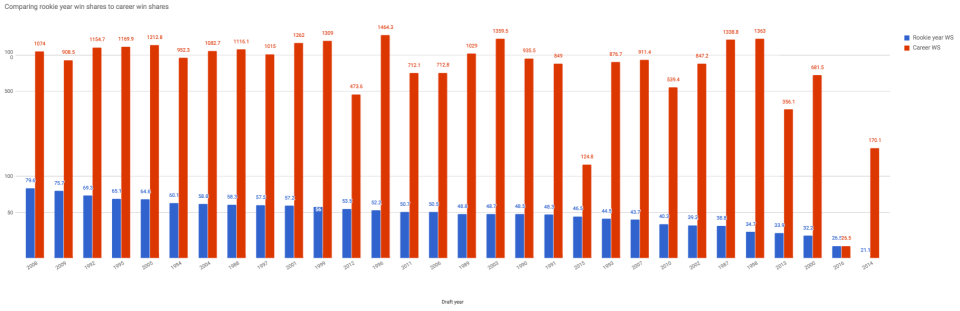

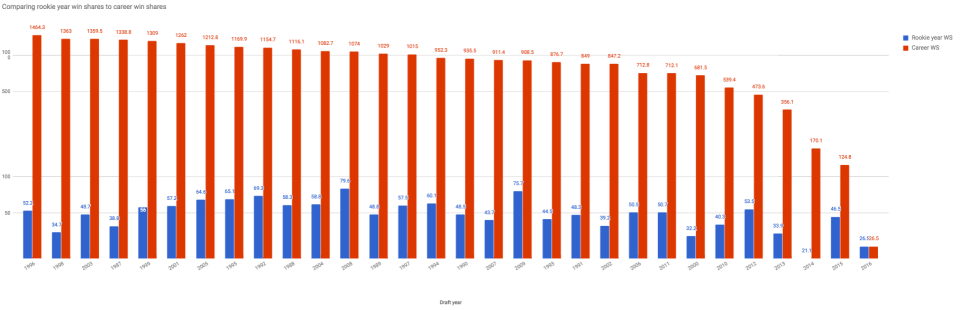

Here are the rookie-year win shares and career win shares for every draft class from the last 30 years, organized from highest-to-lowest first-year total:

By this metric, the aforementioned hallowed 1996 class (13th) and the 2003 class (17th) rank in just the middle of the pack, while the top three rookie-year win share totals belong to 2008, 2009 and 1992. However, when sorted by career win shares, 1996, 1998 and 2003 are the top three classes — and ’98 and ’03 both still have multiple active players.

But this method, while helpful, doesn’t tell the whole story, because longevity plays a huge part in those metrics. For example, as Basketball Reference notes, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is the all-time leader in career win shares because he was able to play at a high level through his late-30s, while Michael Jordan (who played five fewer seasons than Kareem) leads in win shares per 48 minutes.

Yes, longevity is important, but at some point, simply being in the league and continuing to rack up numbers isn’t as valuable as time spent being a top player. So in order to rate the true value of a draft class, it’s important to also look at win shares per player per year, for both the first year and the full career of the rookie class. Then, you can see which groups improved (or declined) after that first season:

There are plenty of examples of draft classes that had poor rookie campaigns, only to develop and produce very good overall careers. The 1998 class, for example, jumped 23 spots from the rookie-year average win share rankings to its place on the career yearly average list. The 2016 class, which finished 29th out of 30 groups in rookie-year average win shares, can draw some inspiration from those two classes. It’s worth taking a deeper dive into those three classes, too.

The 1998 class posted the fourth-worst average first-year win shares since 1989. But with two players — Dirk Nowitzki and Vince Carter — still active, ’98 sits in a tie for fifth place for career average win shares among two-round draft classes.

What changed? Well, the class had little depth in its inaugural season. Just two players — Carter and Paul Pierce — registered at least 2.9 win shares as a rookie. Only two other rookie classes, 2014 and 2016, couldn’t manage more than two.

Nowitzki posted 0.8 win shares his rookie year in Dallas, a year he’d later describe as “jumping out of an airplane hoping the parachute would somehow open” in the book “Dirk Nowitzki: German Wunderkind.” The parachute opened between his freshman and sophomore seasons; Nowitzki registered 8.1 win shares in the 1999-2000 season, and would hit double-digit win shares for the next 11 years in a row. He currently sits at 201.3 win shares for his career, one of only three players drafted in the last 30 years to hit the 200 mark.

More than the depth issue, though, nothing impacted the numbers of the 1998 class quite like the league’s lockout of its players, which limited the season to just 50 games rather than the standard 82. So that group’s first-year to full-career average annual win share spike comes with a massive asterisk attached.

In order to find an example that can provide legitimate hope for sluggish rookie classes like the 2014 and 2016 bunches, the search must be extended past the two-round draft. Luckily, a perfect example emerges just two years before the shift to two rounds.

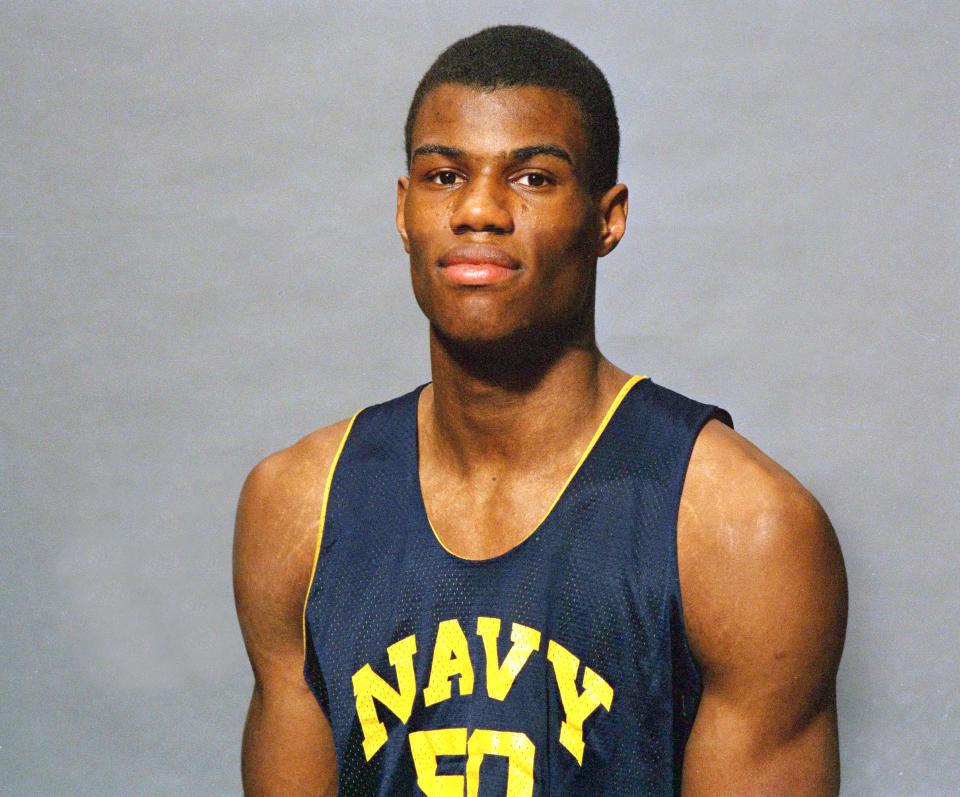

Of the last 30 draft classes, the 1987 class ranks 25th in average first-year rookie win shares, but finished fifth in average win shares per year over the course of its career. The top pick in ’87 was one of the greatest players to ever touch the hardwood, Hall of Fame center David Robinson. But “The Admiral” had to fulfill his commitment to serve active duty as a graduate of the Naval Academy, and he didn’t debut in the NBA until the 1989-90 season. Thus, he didn’t contribute at all to the ’87-’88 numbers.

While Robinson’s absence obviously created a big hole in his draft class’s first-year numbers, it’s still surprising how much this group struggled. New York Knicks point guard Mark Jackson led the way, recording 7.6 win shares. But this is the same rookie class that featured Reggie Miller, Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant, all of whom registered over 100 career win shares, and all three of those players had solid years in ’87. What did this group in was an astounding 18 players who posted negative win shares as rookies — six more than any other draft class in its rookie year since.

Much like Robinson’s absence hurt this draft class in its first year, the loss of injured Philadelphia 76ers lottery picks Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons, neither of whom played a single game in their first seasons due to injury, hurt the 2014 and 2016 classes. Even if they don’t become all-time greats like Robinson, if they can stay on the floor and live up to their potential, they should both greatly impact their draft class’s numbers.

That’s the thing that all the best draft classes have in common: star production from top picks. In the NBA, more than any other professional league, it’s the high picks who have a huge impact on how the draft class is remembered. Of the first five picks in the 2003 draft, three have reached 100 career win shares (James, Wade, Bosh), another (Anthony) should reach the century mark this year, and one (James) has reached 200. Eight of the first 15 picks in the 1996 draft finished with at least 70 win shares, with three (Bryant, Allen, Nash) totaling more than 100, and top overall pick Iverson finishing just one win share short of triple digits.

On the flip side, as you’d expect, classes whose top picks underperform rarely overcome that lack of top-end production. The numbers for the bust-filled 2000 class are startling. No one in the 2000 draft class has hit the 70-win share mark. Every class whose members have completed their careers has had at least two players reach that mark, except for 1990 — and that group’s lone player to hit 70 (Gary Payton, 145.5 win shares) blows 2000’s top dog (Hedo Turkoglu, 63.3 win shares) out of the water.

The top seven picks of the 2000 draft — Martin, Stromile Swift, Darius Miles, Marcus Fizer, Mike Miller, DerMarr Johnson and Chris Mihm — combined to produce 161.9 career win shares combined. Bryant, the top win-share contributor from the ’96 class, had 172.7 by himself.

The 2008 class is worth keeping an eye on, and provides another example of the need for top picks to become stars. Two of the top four picks (Derrick Rose at No. 1, Russell Westbrook at No. 4) have won Most Valuable Player awards, but neither leads the class in win shares per minute; that title belongs to No. 5 pick Kevin Love. This class also shows the importance of a deep draft in evaluating the strength of an individual year. Of the top 10 win share contributors from that class, six — DeAndre Jordan, George Hill, Serge Ibaka, Nicolas Batum, Goran Dragic and Ryan Anderson — were taken outside the lottery.

Even with Rose’s career derailed by injuries and No. 2 pick Michael Beasley becoming more of a journeyman than the superstar he seemed sure to be at Kansas State, based on this strong start, the ’08 class could be on its way to being one of the best ever. On the other hand, while it’s not necessarily time to start worrying about the 2014 class, this season — the class’s fourth — could prove vital.

Rising Denver Nuggets star Nikola Jokic, a second-rounder in 2014, leads the way in career win shares, followed by 23rd pick Rodney Hood of the Utah Jazz and 25th pick Clint Capela of the Houston Rockets. That’s both a good and a bad thing. The early appearance of multiple late-pick contributors is good; that no signature top-of-the-draft stars have emerged isn’t.

It’s a big year for 2014’s top picks. No. 1 overall choice Andrew Wiggins looks to blossom into a true star on a Minnesota Timberwolves team with high hopes. The same goes for No. 7 pick Julius Randle, who has to prove worthy of being a big part of the Los Angeles Lakers’s long-term rebuild. Milwaukee’s Jabari Parker and Philadelphia’s Embiid — No. 2 and 3 overall — have to stay healthy. We’re still not quite sure what to make of Aaron Gordon (No. 4), Marcus Smart (No. 6) or Elfrid Payton (No. 10). Dante Exum, Nik Stauskas and Noah Vonleh (Nos. 5, 8 and 9) are barely hanging onto rotation spots. That’s a lot up in the air for the top 10 picks.

The story’s similar for the rising sophomores of 2016. Simmons’s highly anticipated debut is an important part of a bounce-back campaign this year. The same goes for fellow 76er Furkan Korkmaz (No. 27 overall), who played in Turkey last year but is now stateside. Philly’s Atlantic Division rivals, the Boston Celtics, will welcome draft-and-stash prospects Guerschon Yabusele (No. 16) and Ante Zizic (No. 23) in the near future, too.

As with 2014, there are some positives in the class, too. Brogdon, the 41st overall pick, posted 4.1 win shares, by far the best in the class. Two other non-lottery picks, Denver’s Juan Hernangomez and Brooklyn’s Caris LeVert (No. 15 and No. 20 overall), finished last year third and fourth in rookie win shares, offering some promising early signs of helpful depth to the class.

It’s also worth recognizing that individual players often submit poor rookie years, only to go on to have very solid careers. Allan Houston rated out as the worst rookie in the 1993 class and finished his career with the fifth-most win shares. The same was true of Jamal Crawford after the 2000 class’s first season; now, he’s not only third in his class in win shares, but also the only player currently on an active NBA roster. If he lasts another couple of years, he could very well finish as the best player from that draft. Candidates from 2016 to make similar jumps include No. 2 pick Brandon Ingram of the Lakers and No. 4 pick Dragan Bender of the Suns. Both posted negative win shares in their debut seasons. Both also ranked among the youngest players in the class, with plenty of room to improve.

Yes, the 2016 draft class’s debut was one of the worst in the last three decades. There are some reasons to worry. But history shows there are plenty of examples of classes — and individual players — that bounce back in a major way. The 2016 class might not produce a player close to the caliber of David Robinson; few classes have. But there’s also a good chance that the top picks rebound to have nice careers, and a guy like Simmons becomes a star. If that happens, we’ll look back at this group’s underwhelming debut as nothing more than a small speed bump on the road to a brighter future.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports