100 years after the Tulsa race massacre, one woman’s family is still tormented by racial injustice and police brutality

My great-grandmother would say that up until 1921, you couldn’t tell the difference between Tulsa and New York City. That’s how well Tulsa’s Black community was thriving in the Greenwood neighborhood. Blacks were self-sufficient, independent and wealthy.

But my great-grandmother was keeping a painful secret: The Greenwood that she knew didn’t simply fade away. It was massacred. And that revelation sent me reeling. After all, the destruction of Black Wall Street wasn’t a lesson I had learned growing up in Tulsa’s public schools. It was never mentioned. Not in a textbook or a history class or anywhere else.

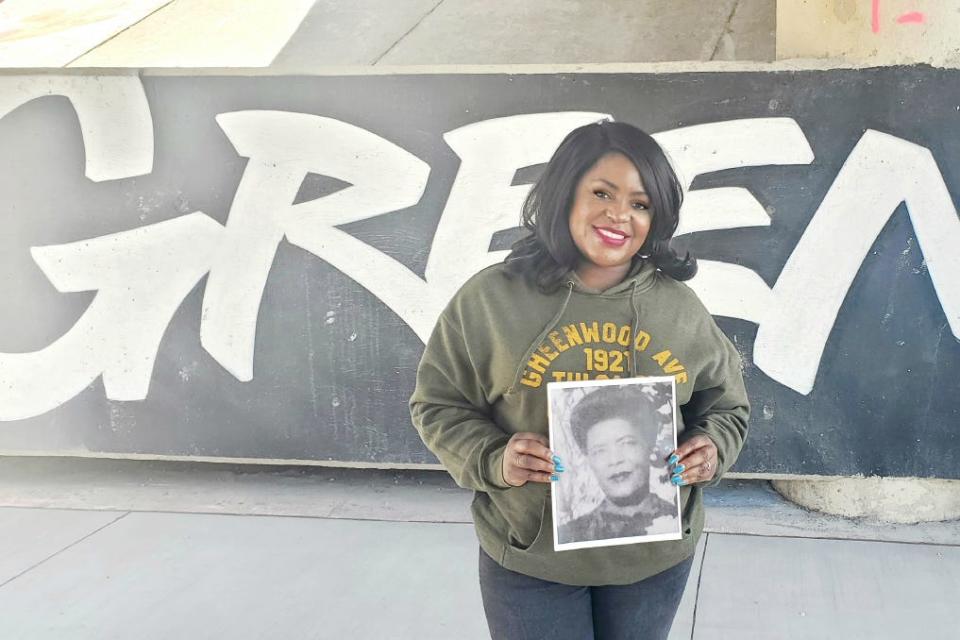

It was only once I became an adult that I learned the truth about my great-grandmother, Rebecca Brown Crutcher, whose family ran a barbecue joint in the heart of the vibrant business district. She was one of the estimated 10,000 Black residents who were driven from their homes when a white mob – many deputized by city officials – descended on Greenwood on May 31, 1921, and burned it to the ground.

As many as 300 Black residents were killed and more than 1,200 Black-owned homes, businesses, schools and churches were destroyed. The city of Tulsa was never held accountable, nor was anyone else. The massacre went unacknowledged for decades.

My great-grandmother passed away. But three massacre survivors are still alive today and deserve justice. Lessie Benningfield “Mother” Randle, 106; Viola “Mother” Fletcher, 107; and 100-year-old Hughes Van Ellis are demanding to receive reparation while they’re still living.

And I’m determined to help them get it.

Battling the city of Tulsa

It’s no surprise that the city of Tulsa doesn’t share the same goal.

It hasn't given a cent to any of the massacre survivors or descendants of massacre victims. This is the same city that empowered the white supremacist lynch mob to mow down the people who built Black Wall Street. It’s the same city whose police officer killed my unarmed twin brother, Terence Crutcher, in 2016 and then tapped her to teach officers how to do their jobs.

In Tulsa, old habits die hard.

Some places and institutions change for the better with time. But Tulsa is proof that a city that finds value in white supremacy will keep it around. It is suspected that 100 years ago, the city dumped Black bodies in unmarked graves. That's around the same time it began burying the truth about the massacre.

“Oklahoma schools did not talk about it. In fact, newspapers didn’t even print any information about the Tulsa race riot,” U.S. Sen. James Lankford of Oklahoma said in a May 2020 local news interview. “It was completely ignored. It was one of those horrible events that everyone wanted to just sweep under the rug and ignore.”

Just this year, the city put a glowing, full-page ad in this newspaper during Black History Month. The promo encouraged tourists to make a “pilgrimage” to Tulsa, describing it as the city that is “leading America’s journey to racial healing.”

Leading America in racial healing? My family is living testimony to the fact that Tulsa’s racial wounds are festering without relief out in the open. Decades after my great-grandmother escaped the massacre by the skin of her teeth, my brother was executed by a white police officer who is still working as a cop. My mother, like so many other Black people in a country rife with health disparities, died of COVID-19 recently. My mother went to her grave without being healed, without having closure. She and my father were inseparable, and he will never be the same.

My widowed father, the children of my slain brother and I live in a deeply segregated city, where the railroad tracks separate the white neighborhood from the Black one, just like they did a century ago. Black Tulsans have suffered years of neglect and systemic racism by successive city administrations that attempted to erase what happened in 1921. The only way we get to a real place of healing and reconciliation is to provide redress – not only for the massacre, but also for the decades of harm that have followed.

Tulsa’s Black community never fully recovered from the 1921 massacre. When our houses and businesses were destroyed, we were not able to apply for property damage claims because some of those reviewing the claims were the same people who caused the damage.

As Human Rights Watch documented in a May 2020 report, “The Case for Reparations in Tulsa, Oklahoma,” the city thwarted attempts to rebuild Greenwood then passed punitive rezoning laws. We rebuilt some of Greenwood anyway, but decades of mortgage discrimination, displacement by a new a highway and other developments hit Black Tulsans hard.

Tulsa’s mayor, G.T. Bynum, dismissed paying reparations as divisive, and has worked instead to push through economic development projects under the guise that they would benefit Black people in Greenwood and the wider North Tulsa area. Predictably, the projects have primarily benefited white business owners and developers.

Earlier this month, throngs of people lined up for the grand opening of Oasis Fresh Market. Before its highly anticipated debut, a full grocery store hadn’t existed in North Tulsa in more than a decade. It was a cause for celebration for Black Tulsans who have been going without. That so many Black Tulsans have lived in a food desert, without access to nutritious and affordable food, is unconscionable.

What's left of Black Tulsa: No happy ending

Only a fraction of what once made up Black Wall Street has been preserved as a Black-owned business district. The rest has been developed to include luxury condos and restaurants that officials said would benefit the Black community. Instead, these projects have largely had the opposite effect, driving up rents and preventing Black businesses from coming in.

It’s no surprise then that Black neighborhoods in Tulsa remain underdeveloped and under resourced. About 34% of Tulsa’s Black population lives in poverty, whereas only 13% of the white population does. We are also subjected to more aggressive policing. Although we make up 17% of Tulsa’s population, we are subjected to almost 40% of the police violence.

It is shameful for the city of Tulsa to claim that it is leading the nation in healing, even as Bynum shows his support for the recently adopted HB 1775, a bill aiming to prevent schools from teaching about systemic racism. This is a city that wants to continue to bury the truth about white supremacy and refuses to consider reparations, even as 106-year-old Mother Randle’s health is fading.

But Black people in Tulsa remain unbowed. It’s with this determination that we are gathering for the Black Wall Street Legacy Festival to commemorate the centennial of the massacre. We are honoring the survivors and descendants of the massacre, and celebrating our resilience in the face of repeated attempts to wipe us off the map. We refuse to be erased. We’re demanding reparations now in Tulsa.

For those looking to Tulsa for guidance on how to move forward from America’s dark history of racism, you won’t find a happy ending. At least not yet. The past will continue to repeat itself in the absence of real contrition that’s backed up by financial redress and institutional reforms.

The survivors and descendants of the Tulsa Race Massacre will not settle for the continuing vestiges of white supremacy. We will not settle for the façade of racial reconciliation that is disconnected from repair. We will not accept empty gestures in this century or in the next one. And neither should anybody else.

Tiffany Crutcher is the founder of the Terence Crutcher Foundation and descendant of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How Tulsa race massacre, police brutality ignited one woman's fight

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports