10 Degrees: Is a juiced ball causing MLB's large home run spike?

At the risk of sounding like someone who believes in chemtrails and listens to Infowars religiously, I have a confession to make: More and more I’m convinced that juiced balls are causing a home run spike throughout baseball.

I am far from the only one. It’s hitters and pitchers and coaches and executives and even rational, cogent analysts who cannot find a reasonable explanation for the spike in home runs dating back to last August. The HR/FB rate – the percentage of fly balls that end up over the fence – spiked over the season’s final two months, and it has continued this April.

With 11.8 percent of fly balls leaving the yard in the season’s first month, it marked the highest April rate since the league started tracking the data in 2002. The number mirrored those of August (12.2 percent) and September (12.3 percent), which Hardball Times analyst Jon Roegele noticed after not even a month. Roegele studied it and came to an impasse.

“I couldn't find anything to describe that amount of HR/offensive change, as far as weather, strike zone, where pitchers were pitching, etc.,” he wrote in an email this week. “I suspected that they changed something with the balls after the All-Star break last year as nothing else in the data could explain it.”

When the email landed, I thought I heard black helicopters whirling above. On the eve of the season, Ben Lindbergh and Rob Arthur at Five Thirty-Eight investigated the HR/FB spike and all the causes that leap to the mind’s forefront. They even sent balls from 2014 and 2015 to a lab for testing to see any differences. None showed. They might as well have been the same.

As much as that should have quelled my interest, the study only emboldened it. One month is one thing. Two months is another. Three is a trend, a pattern, something worth exploring, and with April home runs at their highest rate in more than a decade – 2.77 percent of plate appearances ended with a homer – it warranted a deeper dive.

So I touched base with Dr. Alan Nathan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois and the foremost expert on baseball physics. In trying to understand what happened last fall, Nathan had studied the new exit-velocity data from the league’s Statcast system. While the ball’s speed off the bat had increased ever so slightly in the last two months, Nathan wrote, “a 1 mph change in mean exit speed can account for essentially all of the 13% change in home runs.”

In other words, all it would take to inject offense into baseball is a tiny difference in how the ball leaves the bat. And that difference has continued into this season. Nathan looked at balls with between a 15- and 45-degree launch angle – the optimal trajectory for home run balls. He found nearly 150 more balls were hit this April between 104 and 112 mph compared to last year.

“The conclusion seems to be similar to the early season/late season comparison from 2015,” Nathan said in an email. “Namely, a small increase in exit speeds leads to a big increase in HR production.”

The question, now, is why balls are coming off the bat so much harder now.

“I won't speculate why there might be a small increase in exit speeds,” Nathan said.

Oh, come on, doc.

“It could happen for any number of reasons,” he said.

Like a juiced ball!

“It would appear that the increase in home runs is attributable to exit speeds,” Nathan said, “not atmospheric conditions.”

OK, so weather is out. Now, it’s possible players suddenly, collectively got stronger. Positive tests for performance-enhancing drugs, for example, have jumped this season – there were none last August or September, for whatever that's worth – though as Dee Gordon’s shows, the idea that PEDs exist to aid and abet only home run hitters is false. We can’t discount PEDs entirely, but no evidence exists that drug users – some of whom could use the substances for endurance rather than strength – hit the ball any harder than clean players. Nathan did argue in a paper that PED use would increase muscle mass, and muscle mass would make it likelier a ball go over the fence.

It’s probably not different, higher-quality wood, even as bat regulations have gotten more restrictive in recent years. And while it’s possible this amounts to little more than a big coincidence, three straight months – over two seasons no less – lessens that likelihood.

Like exit velocity, the tiniest changes in the ball can have significant effects, and as much as Major League Baseball focuses on quality control, the ball is the first guess in this game of Clue. A league spokesman said: “We tested the balls halfway through last season and confirmed there was no change in composition from the beginning of the season. We didn’t make any changes in the offseason, either.”

A-ha! In June and July 2015, around the halfway mark of the season, the home run rates were 10.6 and 11.1 percent respectively. And if the ball did change, it was after that, meaning … I’m grasping for straws.

Listen, I’d love for this juiced-ball theory to be more than a theory, for the suggestion from MLB to wind the ball tighter that Ken Rosenthal reported last year to have come to fruition. Nothing beats a great sports conspiracy, and it’s not like this is unprecedented. Three years ago, the commissioner of Nippon Professional Baseball resigned amid a juiced-ball scandal.

Absent some better evidence, the juiced-ball theory remains just that – and it will be the one to which I subscribe, smiling happily underneath a tin-foil hat, which thankfully doesn’t keep me from getting to watch …

1. Nolan Arenado play baseball. Arenado hit his major league-leading 11th home run Sunday, giving him one more home run than strikeout.

Yes, that is real. In this era, where hitters strike out in 21.4 percent of their plate appearances, more than ever, Arenado has whiffed in less than 10 percent of his. Only 10 other players going into Sunday had sub-10 percent K rates, and the only power hitter among the group was another third baseman, Kansas City’s Mike Moustakas.

Currently, Arenado is averaging one strikeout every 9.5 at-bats. Over the last half-century, only seven times has a player struck out that infrequently and hit at least 40 home runs: Albert Pujols twice, Todd Helton, Vladimir Guerrero and Hall of Famers Frank Thomas, Billy Williams and Hank Aaron.

At a time when Mike Napoli is striking out in 39.3 percent of his plate appearances and $132.75 million man Justin Upton in 38.4 percent, it’s especially incredible for Arenado to display such power with such bat control. Just look two spots ahead of him in the Colorado Rockies lineup, where …

2. Trevor Story ranks third with a 36.4 percent punchout rate. This, of course, is not mutually exclusive with success. It’s just unlikely to last unless he changes.

Coming into 2016, only 38 players in history who qualified for the batting title did so with a 30 percent-plus strikeout rate. Of them, only 13 had a sub-10 percent walk rate. (Story currently walks in 8.4 percent of his plate appearances.) That baker’s dozen does not acquit itself particularly well.

The best season of them belongs to Jose Hernandez, who managed to slash .288/.356/.478 despite a 32.3 percent strikeout rate. Nine of them hit below .250. Only Hernandez mustered an on-base percentage better than .326, and five couldn’t even reach .300. Slugging prowess kept Bo Jackson and Chris Davis and Chris Carter and Pedro Alvarez and Pete Incaviglia in everyday jobs, and Story has the advantage of playing shortstop, so he’s going nowhere.

Still, there is too much swing and miss, a refrain that …

3. Giancarlo Stanton continues to ignore in this, his seventh season. He managed five whiffless plate appearances Sunday, bringing his season strikeout rate down to 30.3 percent.

The strikeouts wouldn’t be so frustrating if we didn’t realize Giancarlo Stanton does things to a baseball nobody else in the game can fathom.

Since the start of 2015 @statcast has recorded 77 batted balls 115 MPH+. Giancarlo Stanton has 21 of them.

— Daren Willman (@darenw) May 1, 2016

To put that in perspective, since the beginning of last season, 1,006 players have taken at least one major league at-bat. One man has 27.2 percent of the balls smoked at least 115 mph. When Stanton makes contact, untoward things happen to baseballs, and the time he doesn’t make contact is little more than missed opportunity. His eight home runs this season speak to that, as does his 93.62-mph average exit velocity. Even though …

4. Anthony Rendon is at 92.53 mph, and Dr. Nathan did say 1 mph can make a big difference, it doesn’t mean Rendon should have gone all of April without a home run. And yet here we are, flowers blooming, and he’s one of 25 qualified players without a homer.

There are expensive guys (hello, Elvis Andrus) and other sorts of busts (looking at you, Chase Headley). Guys who need to get their acts together before free agency (Carlos Gomez) and those who may never again (Erick Aybar). Of the group, Rendon is perhaps the best hitter, and that’s what makes his .240/.305/.292 line so disappointing: We saw him hit .287/.351/.473 in his age-24 season, and the 21 previous players to do so in that year – from Stanton to Carlos Gonzalez to Ryan Zimmerman to Troy Tulowitzki all the way back to Alex Rodriguez in 2000 – made at least one All-Star team.

Rendon’s bat these days looks like it’s stuck in quicksand. It takes a line like that of …

5. Jason Heyward to make Rendon feel better about himself. And only a couple handsful in the game this season understand how grim things have been. Heyward is hitting .211/.317/.256 in this, the first year of an eight-year, $184 million deal. So, yes, he’s got 47 other months to produce, and the Cubs certainly haven’t given up on him, plopping him into the No. 2 spot daily.

The lack of power from Heyward, who remains homerless, is still disconcerting. Only seven regulars in all of baseball – including Headley, who entered Sunday without an extra-base hit – have slugged worse than Heyward.

It’s not like he isn’t getting pitches to hit, either. Pitchers have either challenged him or left balls in the strike zone for him, and he hasn’t capitalized. The 46.3 percent of pitches in the strike zone are by far the most he has seen in his career, by more than 3 percentage points.

For all the consolation his glove and patience provide, the Cubs bet nearly $200 million on Heyward in hopes he would tap into the power his 6-foot-5, 250-pound body looks primed to provide. Instead, his average exit velocity is below 90 mph, and he has hit as many home runs as …

6. Jose Quintana and Jason Hammel have allowed: zero. After Hunter Pence took Noah Syndergaard deep on Sunday and Jordan Zimmermann allowed his first tank of the year Saturday, the Chicagoans were the only starters left in baseball with a homerless docket.

Now, this is not to say home runs are a death wish for a pitcher’s success. Drew Smyly, who one scout this week said “is one of the five best starters in baseball right now,” has allowed five home runs. Complementing them with a strikeout rate of 10.64 per nine innings and a walk rating of 1.56 per, of course, helps the pesky home-run issues go way, though it’s easier to do what Quintana and Hammel have done and just not allow any.

Quintana, 27, is striking out more than a batter an inning, walking less than two and a half and suffering no big flies, which all adds up to a sparkling 1.47 ERA. This at least dovetails with his homer-preventing past. Hammel, whose career home run rate is over one per nine innings, may just be the luckiest pitcher in baseball this season, ready to revert to his typical self. Sort of like what the world figures will happen to …

7. Neil Walker sometime soon. And this is not to say Walker is a bad ballplayer, because he most certainly isn’t. It’s just that, well, when you come into your eighth major league season with a 10 percent HR/FB rate and you’re sitting at the beginning of May at 26.5 percent … uh … that doesn’t feel too sustainable.

It’s not as big as Steven Souza’s 41.7 percent (!) or Story’s 34.5 percent, but it’s enough that Walker already is more than a third of the way to his career-high 23 home runs and is imbuing a Mets offense that with Michael Conforto and Yoenis Cespedes raking finds itself renewed and reinvigorated, very similar to an …

8. Arizona Diamondbacks offense whose 38 home runs are one behind MLB-leading Colorado. Arizona’s are coming from the usual suspect (Paul Goldschmidt, six) and some rather unusual ones (Welington Castillo with six, Yasmany Tomas and Brandon Drury with five). And considering Diamondbacks pitchers are getting knocked around even worse than their offense is treating opponents, they need every last one.

It’s worth noting: Home runs don’t exactly equal runs. The highest-scoring team in baseball, the St. Louis Cardinals, have hammered 34 this season, but the next two best, division mates Chicago and Pittsburgh, rank 10th and 16th, respectively. Boston leads the American League in scoring even though it ranked dead last going into Sunday with 19 home runs, which seems like a scant amount until considering Welington Castillo himself has hit more home runs than the entire …

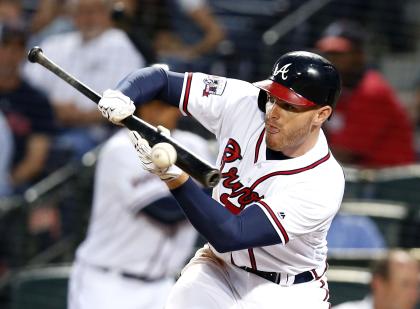

9. Atlanta Braves roster. The Braves went homerless again Sunday, leaving them with five home runs in 909 plate appearances. In major league history, 3,634 players have come to the plate at least 909 times. Only 444 have five or fewer home runs. Of those 444, 87 were pitchers. Meaning the entire Braves roster this season has played like a bottom-10th-percentile-ever power hitter.

What makes it even better is that Atlanta isn’t even the lowest-scoring team in baseball after its 4-3 victory over the Cubs on Sunday. That honor belonged to the Tampa Bay Rays, whose 77 runs through 24 games have negated some of the best pitching in the league. The only thing the Rays’ pitchers haven’t done: prevent home runs, with 30 surrendered, including Troy Tulowitzki’s three-run shot in the ninth inning Sunday. Considering the territory they shared, Tulowitzki is as familiar as anyone with the exploits of ...

10. Nolan Arenado and just how good he is. Arenado is 25. He leads baseball in home runs a year after leading the NL with 42. He won a Gold Glove at third base in his first three seasons, and considering what he did Sunday, it looks like he’s getting even better. This shot from Rickie Weeks came off the bat at 111 mph, and Arenado gobbled it up and threw him out like it was nothing. The entire Arenado video archive is a treat: home runs and grand defensive proclamations and the sort of stuff that makes men want to exaggerate.

Like one longtime baseball sage, who this week suggested if Arenado and Bryce Harper hit the open market today, Arenado would get paid more than Harper. This seemed far-fetched. Good as Arenado is – great as Arenado is – Harper’s bat is extra-terrestrial, and he’s two years younger.

Still, Arenado’s glove – just look at this highlight reel from Sunday – at least makes you pause and consider where he would rank among Harper, Mike Trout, Manny Machado, Carlos Correa, Kris Bryant and the rest of the 25-and-under stars who populate the game.

And he’s up there, high up there, the power, the glove, the contact, everything.

Like Larry Walker and Todd Helton and Tulowitzki before him, Arenado is a talent so big he usurps the advantages Rockies hitters reap from playing in the altitude. Anyone who dare label him a product of that needs a lesson. Even as a juiced baseball may or may not be helping hitters across baseball, Nolan Arenado is saying loud and clear: He doesn’t need it.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports