The man who turned his dead father into a chatbot

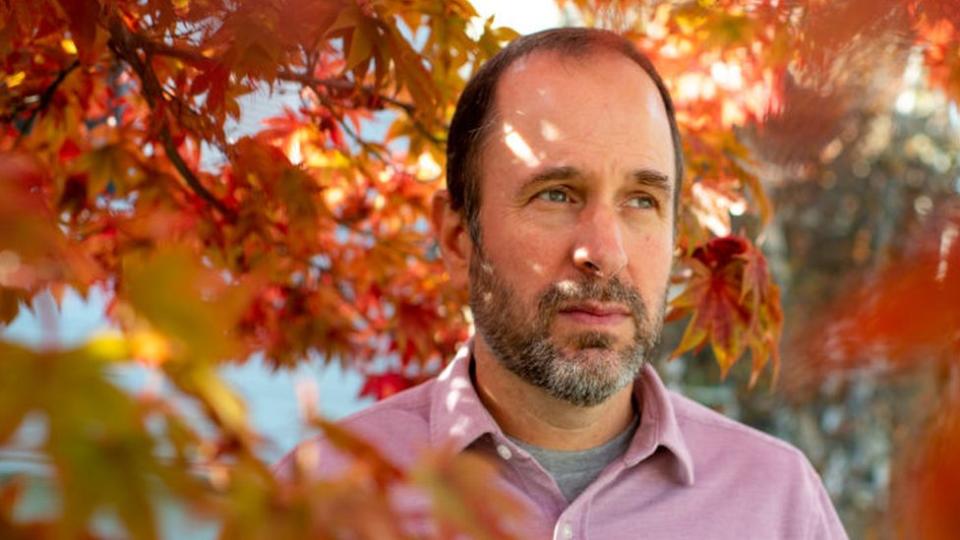

Back in 2016, James Vlahos received some terrible news - his father was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

"I loved my dad, I was losing my dad," says James, who is based in Oakland, California.

He was determined to make the most of the remaining time he had with his father. "I did an oral history project with him, where I just spent hours, and hours, and hours just audio recording his life story."

This coincided with a time when James was starting to explore a career in AI, so his project soon evolved.

"I thought, gosh, what if I could make something interactive out of this?" he says. "For a way to more richly keep his memories, and some sense of his personality, which was so wonderful, to keep that around."

James' father John passed away in 2017, but not before James had turned what he'd recorded into an AI-powered chatbot that could answer questions about his dad's life - in his father's voice.

Such use of AI to artificially bring people back to life has long been explored in science fiction, but developments in AI technology have now made it possible in real life. In 2019, James turned his chatbot into an app and business called HereafterAI, which allows users to do the same for their loved ones.

He adds that while the chatbot didn't remove the pain of his dad's death, it does gives him "more than I otherwise would have". "It's not him retreating into this very fuzzy memory. I have this wonderful interactive compendium I can turn to."

While users of HearafterAI can upload photos of their loved one, to appear on the screen of their smart phone or computer when they use the app, another firm that turns people into AI chatbots goes much further.

South Korea's DeepBrain AI creates a video-based avatar of a person, by shooting hours of video and audio to capture their face, voice and mannerisms.

"We are cloning the person's likeness to 96.5% of the similarity of the original person," says Michael Jung, DeepBrain's chief financial officer. "So mostly the family don't feel uncomfortable talking with the deceased family member, even though it is an AI avatar."

The company believes such technology can be an important part of developing a "well dying" culture - where we prepare for our death in advance, leaving family histories, stories and memories as a form of "living legacy".

The process isn't cheap though, and users cannot create the avatar themselves. Instead, they have to pay the firm up to $50,000 (£39,000) for the filming process and the creation of their avatar.

Despite this high cost, some investors are confident it will be popular, and DeepBrain raised $44m in its last funding round.

Read more stories on artificial intelligence

Yet psychologist Laverne Antrobus says that great care should be taken when using such "grief tech" at times of heightened emotion.

"Loss is something that catches us out," she says. "You can think you're pretty much close to being OK, then something can take you right back.

"The idea that you might then have the opportunity to hear their voice, and hear their words spoken through them, might be quite discombobulating."

Ms Antrobus adds that people shouldn't rush to use a chatbot of a lost loved one. "You'd have to feel quite solid before using something like this. Take things very, very slowly."

The way we grieve is specific to each of us, but that doesn't mean there aren't common experiences.

Red tape is one of them. Banks, businesses and social media sites that your loved one used will need you to complete a raft of paperwork to close accounts, and end direct debits, subscriptions and the like.

"I was looking at more than two dozen companies, and having to phone every single one of them and tell them about my loss," says Eleanor Wood, 41, from South Devon. Her husband Stephen died in March of last year after a serious illness.

"Some of the firms were great and straightforward. Some were outright incompetent and callous. They created more stress and emotional distress at a time when I was already at my lowest possible emotional ebb."

To lessen the administrative burden of the recently bereaved, Settld is a UK online platform that contacts private sector organisations on their behalf.

The user uploads the required paperwork, and the list of everyone that needs to be contacted. Settld then automatically writes and sends off the emails. You can then log back in to check that the firms in question have replied, and that the issues have been dealt with.

It works with 1,400 bodies ranging from banks, to social media firms, to utility companies. It was co-founded in 2020 by Vicky Wilson following the death of her grandmother.

"The more we can do to use technology to lift that admin burden, the better," she says." When someone dies, to deal with the average estate, we're looking at around 300 hours across 146 tasks.

"It normally takes around nine months to wrap up. We reckon around 70% of that work can and should be automated."

The grief tech sector, also called "death tech", is now valued at more than £100bn globally, according to tech news website TechRound.

This growth was fuelled by the coronavirus pandemic, says David Soffer, its editor-in-chief.

"What Covid did was highlight to people the importance of life," he says, stressing that it helped break down some of the taboos around talking about death. This in turn led to us increasingly accepting tech as a part of the grieving process.

"Being able to notify a lot of people at once, remembering people through voice recordings or visual messages are all important," he says.

But Mr Soffer believes the trend has an even more profound meaning. "When technology evolves to solve technological problems, that's good," he says. "But when it helps solve non-technological problems, like the grieving process, that's the real purpose of technology."

Yet Ms Antrobus cautions that there remains no substitute for human support when it comes to overcoming grief. "I can't quite envisage a place for technology to take over the more traditional aspects of grieving, which are around feeling close to people, feeling cared for, feeling appreciated."

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports