Ryan Miller’s Olympic mettle: After Crosby heartbreak, U.S. goalie craves 2nd chance at gold

ARLINGTON, Va. – Materially, the difference between an Olympic gold and silver medal is negligible.

The International Olympic Committee requires that gold medals contain just six grams of actual gold. The discs bestowed upon the champions are actually 92.5 percent silver. The shimmering luster of the ultimate prize is, at its core, not all that dissimilar from what hangs around the first-losers’ necks.

This is of no consolation to Ryan Miller, who understands the excruciating disparity between gold and silver.

The gold medal that dangled from Sidney Crosby’s neck after the 2010 Vancouver Games’ hockey finale represented the fairy tale ending Miller coveted, the championship that eluded him, the hero’s moment. Miller's silver medal epitomized an incomplete journey, an overtime mistake that would haunt him and a defeat that would come to define him as much as the overtime “golden goal” has defined Crosby – or at least it has when the Buffalo Sabres visit Winnipeg.

“I haven’t come to terms with it,” says Miller of the silver.

“We went there to win.”

In 2014, he wants to go back to the Olympics. To complete the journey. To play flawlessly in the final game.

To win gold.

“I want to make the team. I want to be the guy who’s there stopping pucks in Sochi. I want to start. I want to play,” said Miller.

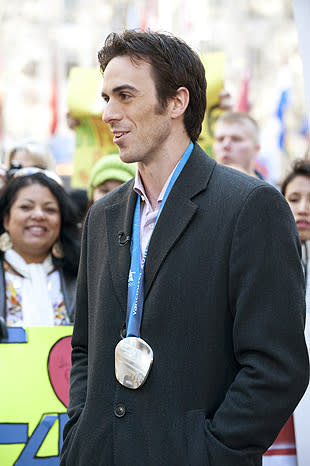

Much has changed since Miller stood inside Hockey Place on Feb. 28, 2010, watching Canada celebrate gold on its home ice and his own run, which earned him tournament MVP honors, end with the silver.

He’s 33 years old, strands of gray now striping his black hair. He’s married, to actress Noureen DeWulf. He’s still one of the most loquacious and thoughtful players in the NHL, but there’s an underlying frustration to many of his comments in the last few seasons. His time with the Sabres appears at an end, with one year left on his contract and Buffalo entering a transition period. He hasn’t seen the postseason since 2011.

His stats have ballooned from their career peak in 2009-2010. Miller is no longer looked upon as one of the League’s top five goaltenders – in fact, he's no longer considered the best netminder for his own country. Most rankings have him eclipsed by many of the American goalies vying for U.S. Olympic roster spots.

“I think even if you asked Ryan Miller, he needs to reestablish his game with the Buffalo Sabres; in conjunction with that, with USA Hockey,” said Ray Shero, general manager of the Pittsburgh Penguins and part of the U.S. Olympic managerial team.

“But he was fantastic in 2010. There’s no denying that.”

***

The selection process for the 2014 U.S. Olympic hockey team measures two primary factors.

The first is “what have you done for me lately?”, as the first three months of the NHL season will determine who has the hot hands and cold feet among Olympic hopefuls. Come out of the gate slowly, and a player risks not making Sochi. Come out of the gate dominating the NHL, and it can mean becoming an integral part of the team. Miller could attest to that: In 2009, he won 16 of his first 22 starts for the Sabres, and earned the starting goalie job for Team USA.

“How you’re playing is the big factor, as it was last time,” said Miller, speaking at U.S. Olympic camp in Arlington, Va. on Monday.

“Certainly your body of work is what gets you invited.”

That’s the second criteria, and Miller’s best case for inclusion on the 2014 roster. He had a 1.35 GAA with a .946 save percentage for the Americans in Vancouver, outright stealing games for a young (and offensively challenged) team.

His athletic, unwavering play earned him Olympic hero status; the name “Ryan Miller” could mentioned with that of Jim Craig among the most impressive goaltending performances by an American in Olympic hockey history.

Is there a sense that Miller is owed the chance to play again in the 2014 Games, as repayment for his performance in 2010?

“I don’t know if anybody’s owed anything,” said Shero.

“What do you owe a player that plays for his country?” asked Brian Burke, the GM of the 2010 team and part of the 2014 team’s managerial braintrust.

“It’s body of work. He’s very much alive for a starting goaltender position. So is Jonathan Quick. So is Craig Anderson. He’s been phenomenal the last couple of years. We’re not going in with anyone penciled in as 1 or 1-A.”

The strength of the U.S. team is, without question, in goal. Along with Miller, the team will choose from Quick, a former Conn Smythe winner; Anderson, who can carry a team on his own for weeks at a time; Jimmy Howard, the steady goalie for the Detroit Red Wings; Cory Schneider, who went from Roberto Luongo’s understudy to Marty Brodeur’s heir apparent with the New Jersey Devils; and John Gibson, the Anaheim Ducks prospect that led the U.S. to world juniors and world championship gold.

It would take a Herculean start to the season -- and maybe some bad luck befalling the competition -- for Miller to win the job, with both Quick and Anderson vying for it. (USA Hockey sources say it’s Quick’s to lose.) But it’s not out of the question he could be one of the three goaltenders the Americans take to Sochi.

Would the 2010 starter as the 2014 backup put too much additional pressure on, say, Jonathan Quick?

“I would hope not. Depth and competition are healthy,” said Shero, who would know a thing or two about creating a goaltending competition as Penguins GM.

Shero noted that Miller was looking over his shoulder at former Boston Bruins goalie and Vezina winner Tim Thomas in Vancouver. “Thomas played 10 minutes in the entire tournament. But he was there and it was healthy competition” Shero said.

Miller said he wasn’t necessarily irked or driven by the presence of Thomas.

“I actually felt comfort in it,” he recalled. “If I didn’t do well in the preliminary rounds, we had a good group of guys that could take over.

“I was going to play aggressive, push my game. If it didn’t work out, there was someone else there. It’s going to be the same situation this time.”

Miller just doesn’t know if he’d be the starter or the safety net.

“I’m not going to worry about it. This is wide open. Whoever is going to be the best option going into it is whoever’s playing the best,” he said.

“I’m concentrating on my NHL start, and trying to get to the right place so I can make this team. Your past does factor in a little bit, but it’s how you’re playing in the moment.”

***

The moment that’s come to define Miller happened at 7:40 of overtime in the gold medal game against Canada.

He doesn’t dwell on Crosby’s goal. It doesn’t haunt him like it once did. But ask Miller about it, and he begins breaking down the play with equal parts technical analysis and regret.

“I played the tournament aggressively. I saw an opportunity where he … he obviously didn’t mishandle the puck, but the puck came into his skates on a pass. I thought he was going to change his angle, and he didn’t,” said Miller.

“I made a decision that I anticipated something was going to happen and it didn’t happen, and I made a mistake. And it is what it is. It went in the net, and no one feels worse than I did.”

While the agony of that defeat has lessened since Vancouver, the disappointment lingers. Some felt the Americans should have been content with silver, happy to have gotten to a championship game that powerhouses like Russia and Sweden failed to reach. That was far from the impression the U.S. players had, as well as that of their general manager.

“Brian [Burke] wasn’t blowing hot air, even though sometimes he does,” said Miller. “The one thing he did say was that we were going there to win, and he wasn’t lying, and that was the attitude we had. It took a while for everyone to catch up to us, that we could do it.”

With a win over Canada in preliminaries, Miller and his teammates were convinced they could capture gold.

“It was that time when you think you can do something and then you get some positive feedback and then you know you can do something. I think everybody in that room, we knew we could win,” he said.

“It was very disappointing. It is to this day. It’s not a sore subject anymore, but it’s bittersweet. It was a great two weeks. A lot of fun to play hockey at such a high level, in a place where they respect hockey. But it wasn’t the fairy tale ending.”

That’s what Miller’s chasing now, and desperately wants to experience.

But his legacy won’t punch his ticket for Sochi – he’ll have to earn it again.

"The job I did was three and a half, almost four years ago. You can’t stack that in the net behind you and have it deflect pucks away for you. You have to re-focus, reestablish," said Miller.

"And start over.”

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports