The story of Cookie Gilchrist, one of the CFL’s most fascinating alumni, in his own words

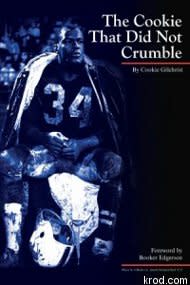

Sports books often don't break much new ground, and that's particularly true in the case of books "written" by athletes or coaches (but really pencilled by the scribes who co-author them). The Cookie That Did Not Crumble, an enthralling new book by CFL and AFL legend Cookie Gilchrist and co-author Chris Garbarino, is a refreshing exception to that rule. Unlike many athletes' books, Gilchrist's unfiltered voice comes through loud and clear in this one, and that has to do with how this was put together. Following Gilchrist's death in January 2011, his son Scott asked Gabarino, who'd struck up a deep friendship with Gilchrist, to collect Gilchrist's old journal and manuscripts and work them into a book. Gabarino has done a superlative job with that, presenting Gilchrist's story in the man's own words, including brief bits of context where necessary and keeping the narrative flowing at all times.

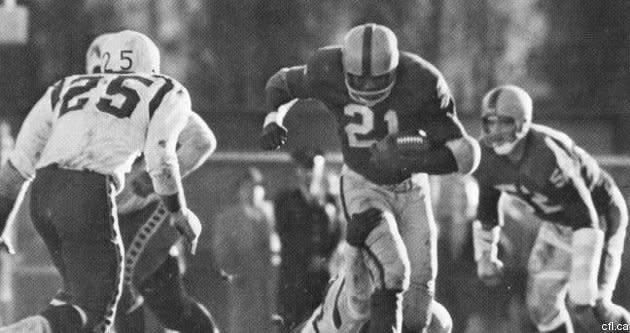

The result of Gabarino's efforts is a captivating read that details not just Gilchrist's tremendous playing career in the CFL (with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, Saskatchewan Roughriders and Toronto Argonauts) and AFL, but also gives deep insight into plenty of heretofore largely unexplored territory. Some of the best sections include his dealings with everyone from former CFL commissioner and Tiger-Cats' general manager Jake Gaudaur to famed NFL coach Paul Brown, notorious Toronto Maple Leafs and Hamilton Tiger-Cats' owner Harold Ballard, singer Marvin Gaye and boxing legends Sonny Liston and Muhammad Ali. It's much more than a book about football games; the games are there, but the work as a whole studies themes of racism and discrimination in both the U.S. and Canada, the crippling injuries and difficult post-football careers players are often left with, and the challenges involved in making any progress to help former athletes.

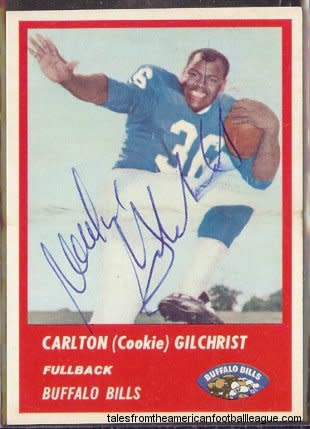

The CFL portions of the book are notable for their inclusion and detail as well. Given the higher-profile nature of Gilchrist's time in the AFL with the Buffalo Bills (who he's seen playing for at right), Denver Broncos and Miami Dolphins and his amazing encounters with everyone from KFC's Harland David "Colonel" Sanders to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, it would have been tempting for many authors to gloss over Gilchrist's early days and jump to the point when he caught the attention of the American public. Garbarino doesn't do that, though, and the book is much better for it; rather than merely being a listing of Gilchrist's most famous accomplishments, it's a thorough look at his different experiences and how they shaped him.

Speaking of those experiences, the book brings up several issues many CFL and NFL fans may not be aware of, particularly with regards to how much of a role racism may have played in the leagues' early days. Gilchrist reports being called various racial slurs throughout his 1955 season with the semipro Kitchener-Waterloo Dutchmen, and those followed him throughout much of his playing career. There was substantially more than just name-calling, though. For example, after an impressive 1956 season with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in the Big Four (which would become the CFL's East Division), Gilchrist was offered a chance to return to the U.S. and play for the NFL's Cleveland Browns, but only on the condition he end his relationship with a white Canadian girl he'd met. Here's what he wrote on the subject:

"The NFL would not accept interracial relationships. Our relationship would be a public relations nightmare for them, and that was a take-it-or-leave-it condition of their offer. While I would have loved to play back home on the NFL stage, I realized that I loved Gwen more and saw a better future for us in Canada."

Canada in the 1950s and 1960s was no paragon of racial harmony, though. Black players had to room together on the road, and they were often used on the field only to set up whites for scoring plays. Many also wound up with further difficulties off the field, including in contract and trade negotiations: Gilchrist relates how Gaudaur reneged on a contractual bonus he was due with the Tiger-Cats, how he felt Toronto Argonauts' coach Lou Agase took him out in favour of white players and how Argonauts' general manager Lew Hayman wound up waiving him over a curfew violation. Gilchrist wrote that this history of poor treatment based on his race was what led him to initially decline induction into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame (he later was willing to accept it, but that sadly didn't come to fruition) when Gaudaur, by that time the league commissioner, offered it in 1983.

"I loved the Canadian people; especially the fans who'd watched me play in the ORFU and CFL. But I felt that several of the CFL elite had taken advantage of me at the height of my career. I felt that if I accepted the honor from those who mistreated me, I would be condoning what happened in the past. In addition to the poor treatment I received from several coaches and owners off the field, all of the times I was punched, kicked or cursed on the field just because of the color of my skin remained a vivid memory. I thought that by declining the honor I could bring new light to what had happened to me and other players of color. At least the issue would spur on serious dialogue about player treatment now and in the past."

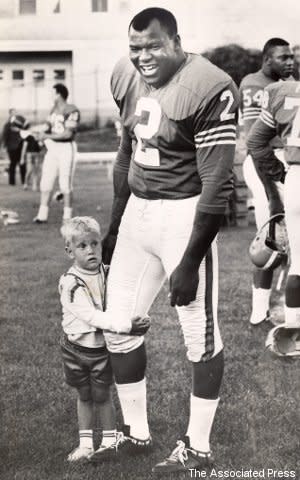

Player treatment was a focus of Gilchrist's throughout his CFL and AFL careers and long after. He was a crucial figure in the boycott of the 1965 AFL All-Star Game over segregation in New Orleans, one of the most important athletic steps in the Civil Rights Movement. After his playing career ended, Gilchrist came up with an even more ambitious idea, founding the United Athletes Coalition of America and Canada with a goal of providing help for future, current and former professional athletes across both countries. The coalition envisioned promoting the value of athletics and education to troubled youth, providing marriage counselling, private therapy and substance abuse treatment to current and former athletes and supplying former athletes with assistance finding post-sports job opportunities and developing marketable skills.

The coalition was a superb idea, and it received substantial endorsements from everyone from NFL stars like Jim Brown and Joe Namath to famed coaches like John Madden, key figures in other sports like Ken Dryden, Wilt Chamberlain, Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and Sugar Ray Robinson and crucial entertainment and media types like Gaye, Sammy Davis Jr., Howard Cosell, Dick Ebersol and Jim Proudfoot. Key figures in the attempts to get it off the ground included Gilchrist's Buffalo teammate Jack Kemp, who was a U.S. Senator Congressman by that time, his Broncos' teammate Charlie Janerette and CFLPA attorney John Agro. However, the organization struggled to raise funds and was overlooked by government and sport partners in both the U.S. and Canada.

It looked like Gilchrist had found a way to bring in the money the coalition needed to get going thanks to a tremendously successful Gaye benefit concert he organized at Maple Leaf Gardens, but Ballard wound up reneging on the deal they had and keeping the organization from getting the proceeds. That's not particularly surprising to anyone who's read much about Ballard (seen at right), who was notorious for similar stints during his time running the Toronto Maple Leafs and Hamilton Tiger-Cats, but it's still a tragic end to a great idea. Eventually, the coalition ran out of money and took a lot of Gilchrist's savings with it. Its ideas were prescient, though, and many were later adopted by professional leagues and players' associations across North America.

Gilchrist's later life shows just how important post-career programs for athletes can be. He wound up living a rather isolated existence and often faced issues coping with day-to-day life. A chance friendship he struck up with Gabarino proved vitally important, as Gabarino wound up being one of Gilchrist's key confidants and helped put him in touch with NFL alumni programs like "The 88 Plan" that turned out to be crucial in his later life. Gilchrist needed the help; although he was still in command of his faculties much of the time, he'd have days where he completely forgot previous conversations and struggled to deal with his medical issues. Gilchrist wrote in his journals during his career that he was concerned about the toll head hits were taking on him, and that proved accurate: after his death, in accordance with his wishes, his brain was examined by the Boston University-affiliated Sports Legacy Institute, and they reported in June that Gilchrist had indeed suffered from stage IV of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the most serious classification of the condition.

CTE has been found in the brains of many other football players, including Gilchrist's Argonauts teammate Bobby Kuntz, and these findings are driving much of the current push to reduce the occurrence of concussions and properly treat them. For the former players who already deal with their effects, though (a frighteningly large number, as can be seen in pieces such as The Hamilton Spectator's look at Tiger-Cats' alumni and Sports Illustrated's profile of the 1986 Bengals 25 years later), it's vital that programs and treatment are in place to provide them with whatever they need.

Caring for players after football was one of Gilchrist's key goals, and perhaps his story and his book can provide further motivation to intensify those efforts. It's not always the most polished prose, but Gilchrist's passion and intensity shine throughout the work, and his incredible story gives great insight into what things were really like in the early days of professional football. For any football fan looking to learn more about the past of the CFL and the AFL, or anyone who'd like to learn more about one of sports' most remarkable athletes, this one is a must-read.

For more information on Gilchrist's life and the book, including how to order it, visit www.cookiegilchrist.com.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports