Tuesdays with Brownie: The burden of managing

(A weekly look at the players, teams, trends, up-shoots and downspouts shaping the 2015 season.)

The Miami Marlins are not very good, which is an alarming development for owner Jeffrey Loria and a source of some curiosity for those of us with zero emotional (or financial) stake in the franchise that arguably deserves little in the way of emotional (or financial) investment.

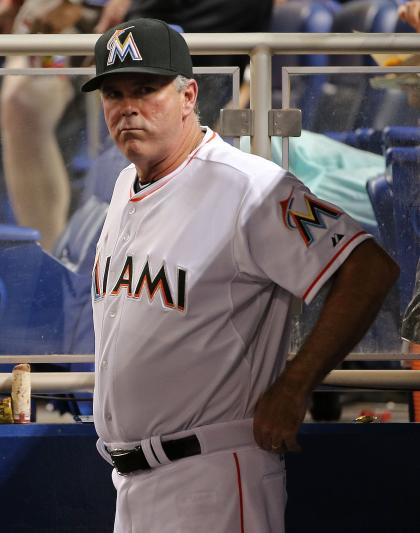

The problem, it would appear, is not the manager, as the Marlins were 16-22 under Mike Redmond and are 4-10 under Dan Jennings, though there’s a reasonable argument the Marlins didn’t change managers as much as they transitioned from a manager to something else entirely. You could almost understand what Loria and his lieutenants were reaching for when they made the drastic decision to can Redmond and followed that with the extraordinary decision to replace him with Jennings, however.

In the NBA, for example, head coaches generally run games with similar strategies. They match up, they call timeouts, they rest players, they run plays for the guys who can make shots, they ask/beg/plead for them to please-please-please play some defense. The best coaches (and, granted, many of the best coaches have the best players) find a way to motivate seven or eight players to play hard most of the time, even in December, even amid the usual internal disputes over whose ball, whose minutes, whose shots, whose team. See, players play for a good coach, someone they believe in, or at the very least don’t not believe in.

It’s an underrated facility for a baseball manager. That is, getting nine – or 10 or 12 – men to play with some urgency as many times out of 162 as possible. The longer the season, the more difficult the task, and there’s nothing longer than a baseball season. Marlins management – Jennings included – looked across a roster (it created) and decided it wasn’t the talent but the direction of the talent (perhaps a self-serving conclusion), and so here they are, good-guy Jennings running baseball games, and losing them, too.

Forget for a moment that it was easy for players to like Jennings when he wore a tie and wasn’t making the lineups (presumably) and wasn’t having to think his way through the last three innings. Forget that everyone has one opinion of management from a distance and another when it’s leaning over a shoulder for eight hours. Baseball is a brutally hard game that softens gross amounts of failure with a moment or two of happy achievement. The men who play it develop long perspectives and healthy rationalizations in order to retreat from the oh-fers and make it look like a parade.

So, yeah, they love a good guy on the top step. They love an understanding soul who protects them from criticism and distraction. They love a man who leaves them be, treats them as adults and stays out of the way.

Right up until the good guy on the top step starts losing them games, or operates in a manner that suggests he’s losing them games, or manages just close enough to the line where they can decide he – and not they – are responsible for them losing games. It amounts to the same coping mechanism that gets them through those oh-fers, or that dreadful start, or a blown save. It’s how they’ve survived this long. Now the manager serves the easiest path to the most convenient excuse, and that – along with whatever frailties he has as a manager who’s never managed before – is the fight for Dan Jennings. And one day, maybe soon, that will be the reason the Marlins give up on this experiment and give the job to someone whose reputation resonates in the clubhouse, whether Jennings can manage or not.

Managing expectations

Sometimes, even the reputations don’t help. So the drumbeat builds in Boston, in San Diego, in Toronto, in Chicago, in Cincinnati, wherever there were expectations to be had and, two months later, underperformance to be found.

In Milwaukee, the Brewers were 7-18 under Ron Roenicke and are 10-16 under Craig Counsell. The Marlins haven’t changed much at all under Dan Jennings. The Houston Astros and Minnesota Twins – with A.J. Hinch and Paul Molitor – seem to have discovered some kind of magic, or competency, or something, as have the Chicago Cubs with Joe Maddon. The Astros and Cubs are merely a year or two ahead of schedule. The Twins, though? June dawned and the Twins weren’t just a mild curiosity, they had the best record in the American League and with but 113 games remaining, which only seems like forever.

In Boston, not two years after a parade you might recall, folks are starting to kick around John Farrell’s fitness for the job, and that’s silly, but that’s the job. As of today, the Red Sox have given no – zero – thought to replacing Farrell, according to sources. For one, Farrell is actually pretty good at this, despite the 93-120 record since they fueled up the duck boats. (Let’s try not to forget the 97-65 record he posted when the Red Sox had better players.) For another, the AL East leaves no man behind. The Red Sox have a ways to go to actually be good, but it’s not far at all to the top of the division.

To that end, the Red Sox are not yet highly engaged on the bigger draws of the coming trade market (not Cole Hamels, not Johnny Cueto, at least not yet), and instead are focused on more minor upgrades. They need new starting pitching or, perhaps, their current starting pitching to be better. They need some life out of Pablo Sandoval. They need Hanley Ramirez to be April Hanley and not May Hanley. The whole team just batted .237 and scored 82 runs … over a month. (The Texas Rangers nearly doubled those runs in May. The Tampa Bay Rays outscored them by 23 runs in May.)

It’s not a Farrell problem. It’s a roster problem. Red Sox management is focused on the latter.

Reviewing the review system?

The replay system has been kicked around some for the first couple months, as some managers believe they’ve seen too many plays incorrectly called in spite of the technology. Angels manager Mike Scioscia, for one, would like MLB and the players’ union to consider appointing an independent body that would review replays rather than a rotating umpire crew. Under the current system, umpires in the room are tasked with confirming or overturning calls by fellow umpires.

Scioscia suggested retired umpires or supervisors or, perhaps, younger umpires who’ve tired of waiting for a big-league job.

Umpiring, and therefore replay, falls under Joe Torre’s purview. He is mostly satisfied with the system and the results, he said Monday afternoon, except that the league had hoped to quicken the review times. Through nearly two months of 2015, the average time of review is one minute, 47 seconds. All of last season the average time was one minute, 46 seconds.

“Right at this point,” Torre said, “I don’t see any change that we are looking forward to making. We’re still in the process of just doing what we do. We really don’t have anything we’re itching to change.”

He has spoken to Scioscia, who has been vocal in his displeasure with replay outcomes, both for and against the Angels. Torre said he hoped to have Scioscia tour the replay facilities later this week, when the Angels are in New York, and to further the conversation about the system.

Umpires, he said, seem to prefer another umpire at the end of the phone line.

“For their comfort level,” Torre said, “the fact there’s an umpire basically correcting another umpire is a credibility thing.”

Through May 28, there had been 349 reviews. Of them, 78 (22.3 percent) were confirmed, 103 (29.5 percent) stood (not enough evidence to overturn or confirm) and 165 (47.3 percent) were overturned. There were three rules checks.

Those percentages are freakily similar to the 2014 results. Of 1,275 reviews, 22.3 percent were confirmed, 27.6 percent stood and 47.3 percent were overturned.

The Trout effect

Mike Trout is doing all those Mike Trout things again, the usual routine of speed and power and having everyone forget he’s 23, which is how old Kris Bryant is.

Perhaps the only difference is opponents’ growing unwillingness to allow him to be Mike Trout as often. Intentionally walked only six times last season, primarily because Albert Pujols usually was on deck and no matter the numbers the man is still Albert Pujols, Trout has been so avoided eight times already in 2015. Pujols awaited in six of them, including again Monday night against the Tampa Bay Rays.

The result? Pujols is one for five with a sacrifice fly and two walk-off RBIs. He flied out Monday night after Kevin Cash passed on Trout, but Pujols otherwise homered twice, further fueling a 15-game run in which he’s batting .322 with seven home runs and a 1.094 OPS. He has five home runs since Thursday, bringing his season output to 13, same as Trout.

A prideful hitter, Pujols said the choice by foes to pitch to him and not Trout is good by him, though the withering glare he shot the Padres’ bench last Monday after a walk-off single perhaps said something else. “They can do that a hundred more times,” Pujols said after his two-homer night against the Rays. “It doesn’t bother me.”

His second home run came in the eighth inning, two innings after Trout had been walked intentionally and he’d followed with an inning-ending fly ball. A bat flip that was mostly subtle chased the home run.

Trout smiled.

“I guess when you hit 500 of them, you can watch ’em,” he said. “I don’t think anybody’s going to say anything.”

Angels coming alive

In their five-game winning streak, which included a four-game sweep of the Detroit Tigers, the Angels’ offense – the best in baseball in 2014 and a huge disappointment for two months of 2015 – scored 33 runs. It doesn’t solve everything, and it doesn’t bring Howie Kendrick back, and it doesn’t lessen the spiteful decision to shove Josh Hamilton out the door, but it’s something.

They needed something.

Of eight positions and designated-hitter, the Angels are getting below-average production by OPS in all but center field. That’s where Mike Trout plays.

More MLB coverage:

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports