Ted Kaczynski, Domestic Terrorist Dubbed the Unabomber, Dead at 81

Ted Kaczynski, the domestic terrorist known as the Unabomber who killed three people and injured dozens in a series of mail bombings that spanned decades and long baffled authorities, has died at the age of 81.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons confirmed Kaczynski’s death Saturday, adding he was found dead in his prison cell at a medical facility in North Carolina, ABC News reports. The New York Times added that Kaczynski died by suicide.

More from Rolling Stone

Kaczynski, who was serving multiple life sentences in prison after pleading guilty in 1998 to 16 bombings — a plea deal that allowed him to avoid the death penalty — was transferred from his longtime supermax Colorado prison to North Carolina’s FMC Butner last December, a facility that typically treats inmates with significant health problems, the Washington Post reported.

Dubbed the UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) long before his capture in 1996, Kaczynski was the focus of a manhunt that at the time was the longest and most expensive in the history of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The investigation began in 1978, seven years after the Chicago-born, Harvard-educated Kaczynski left his job teaching mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley and built himself a remote cabin in rural Montana.

“Ever since my early teens I had dreamed of escaping from civilization — as in going to live on an uninhabited island or in some other wild place,” Kaczynski said in a 2001 interview. “The trouble was that I didn’t know how to go about it, and it was extremely difficult to work up the nerve to cut loose from my civilized moorings and take off to the woods. It’s very difficult because sometimes we don’t know how much the choices we make are governed by the expectations of people around us, and the fact that we go and do something other people would regard as mad — it’s very difficult to do. Furthermore, I didn’t know where to go really.”

Kaczynski’s first mail bombings — sent during a period in the late Seventies when he returned to his native Chicago to work at a foam factory alongside his father and brother — targeted Northwestern University faculty members; a campus security guard and graduate student received minor injuries when both packages detonated.

In November 1979, one of Kaczynski’s bombs failed to detonate while aboard an American Airlines flight, causing smoke inhalation among passengers but averting tragedy. It was that incident — coupled with a June 1980 mail bomb sent to United Airlines president Percy Wood, causing severe cuts and burns — that drew the attention of the FBI, sparking an investigation and manhunt that lasted 15 years and an estimated $50 million until Kaczynski was apprehended in 1996.

Over the next five years, Kaczynski, himself a former math professor, targeted professors at institutes of higher education (The University of Utah, Vanderbilt University, and two bombs both mailed to UC Berkeley and University of Michigan). While Kaczynski’s victims suffered injuries ranging from severe burns to permanent hearing loss, no one was killed by his devices until December 1985, when he targeted a Sacramento computer store owner by placing a nail bomb in the parking lot of the store, killing its owner Hugh Scrutton.

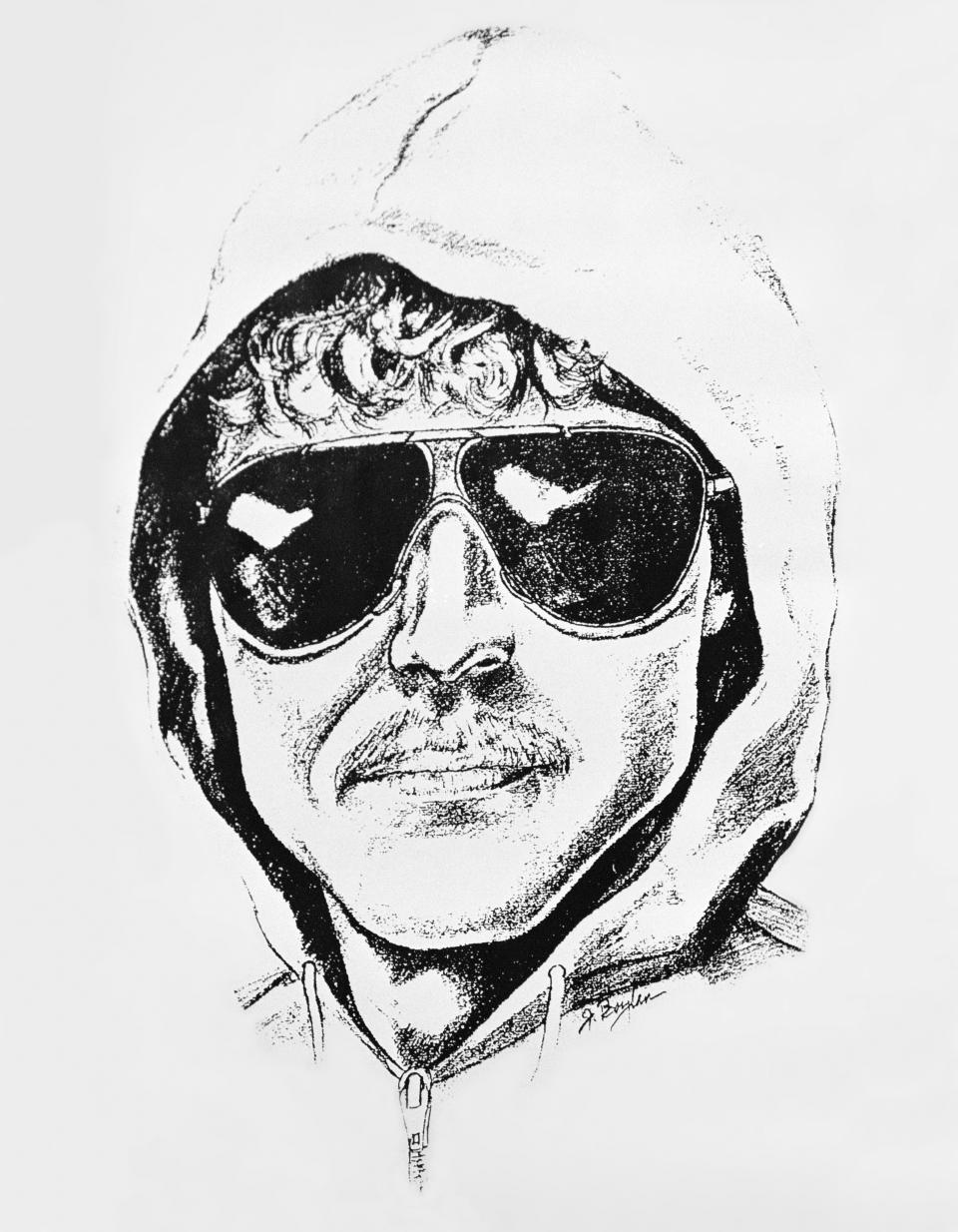

In February 1987, Kaczynski placed a similar device outside an Utah computer store, with its owner suffering nerve damage in the blast; during that incident, Kaczynski was witnessed at the scene placing the device, resulting in the police sketch that was long associated with the Unabomber, a man wearing sunglasses and a hoodie.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

The common thread that tied together Kaczynski’s intended targets was his stance on anti-industrialism, anti-deforestation and a concern about modern technology, particularly the rise of computers. In 1995, after a pair of mail bombs killed a New Jersey advertising executive and a California timber lobbyist — the second and third people killed by his devices — Kaczynski sent a 35,000-word essay, Industrial Society and Its Future, to numerous major newspapers, promising more victims unless the essay, later dubbed “the Unabomber manifesto,” was published. The Washington Post acquiesced with the demand, publishing the full essay as an eight-page supplement in their Sept. 22, 1995 newspaper.

“The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race,” Kaczynski wrote – under the pseudonym FC, or “Freedom Club,” the same initials etched into some of his bombs – in his introduction. “They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in ‘advanced’ countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation.”

In some ways, the Unabomber’s manifesto was prescient in its skepticism toward technology. “A technological advance that appears not to threaten freedom often turns out to threaten it very seriously later on,” he wrote at the dawn of the internet era. “Another reason why technology is such a powerful social force is that, within the context of a given society, technological progress marches in only one direction; it can never be reversed. Once a technical innovation has been introduced, people usually become dependent on it, so that they can never again do without it, unless it is replaced by some still more advanced innovation.”

(Ishmael author and environmentalist Daniel Quinn once said of Kaczynski’s beliefs, “The Unabomber, for example, is convinced that our problem is really very modern, and that if we just go back a couple centuries and smash all the machinery, everything will be wonderful again. I trace our problems back to the beginnings of our culture. I make a point really that it is not humanity that is destroying the world, it is one culture… it happens to be our culture, the dominant culture on the planet.”)

However, Kaczynski’s manifesto — which condemned both “leftists” and conservatives — was also laced with writings that would align with the current far-right movement. “Leftists tend to hate anything that has an image of being strong, good and successful. They hate America, they hate Western civilization, they hate white males, they hate rationality,” he wrote.

Kaczynski, who branded himself an anarchist and a revolutionary in the essay, continued, “It would be hopeless for revolutionaries to try to attack the system without using SOME modern technology. If nothing else they must use the communications media to spread their message. But they should use modern technology for only ONE purpose: to attack the technological system.”

A week after the manifesto was published, Kaczynski’s brother David — whose wife Linda Patrik privately questioned whether Ted could be the Unabomber — compared the writings to those Ted made decades earlier. “I thought I was going to read the first page of this, turn to Linda and say, ‘See, I told you so,’” David Kaczynski told ABC News in 2016. “But on an emotional level, it just sounded like my brother’s voice.” Now convinced his brother was the Unabomber, David hired his own private investigator to look into his brother, with those findings and the other evidence later sent to the FBI.

Nearly seven months after the publication of his manifesto — a period where no more mail bombs were sent — Ted Kaczynski was arrested at his Montana cabin on April 3, 1996. Two years later, he pled guilty to all charges to avoid the death penalty and was sentenced to eight consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole.

On the night of Kaczynski’s April 3rd, 1996 arrest, late-night radio host Art Bell told his audience, “We contend with so much here. So much violence, so much contention, and yet you hear from a little country like Belize where the only thing shot is the occasional beer can. Why do you think that would be? Why do you think Americans and America — civilized, industrial, with technology that frankly is ahead of just about all of the rest of the world — and we have so much violence. I’m sure the Unabomber would have something to say about that.”

Behind bars, Kaczynski became a prolific writer, often penning lengthy responses to mailed correspondence as well as partaking in interviews. In an essay titled In Defense of Violence, Kaczynski attempted to justify his spree of terror. “My lawyers brought a neuropsychologist, a Dr. Watson, to give me some tests to verify that I wasn’t crazy. After the testing was done, Dr. Watson asked me some questions about my bombings,” Kaczynski wrote.

“Among other things, he asked me how I felt about the impact of my actions on the ‘victims’ and their families, and he seemed rather troubled that an intelligent man like me could kill people without feeling much guilt and without worrying very much about the impact on the dead mens’ families. But if I had been a soldier who had killed or maimed enemy soldiers in a war, it would not even have occurred to Dr. Watson to ask how I felt about the impact on the victims or their families. No one expects a soldier to hesitate in killing enemy soldiers or to worry about how the dead men’s families feel, and very few soldiers do worry about such things. This shows that most people’s attitude toward violence is governed not by compassion but by social convention.”

Kaczynski’s manifesto and writings have reportedly influenced mass shooters and domestic terrorists — Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 people in Norway in a 2011 bombing and mass shooting, copied passages from Kaczynski’s Industrial Society and Its Future in his own “manifesto” — as well as sects ranging from the far-right to “eco-fascism.”

Best of Rolling Stone

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports