Sen. John McCain was a passionate boxing fan and his criticisms helped shape modern MMA

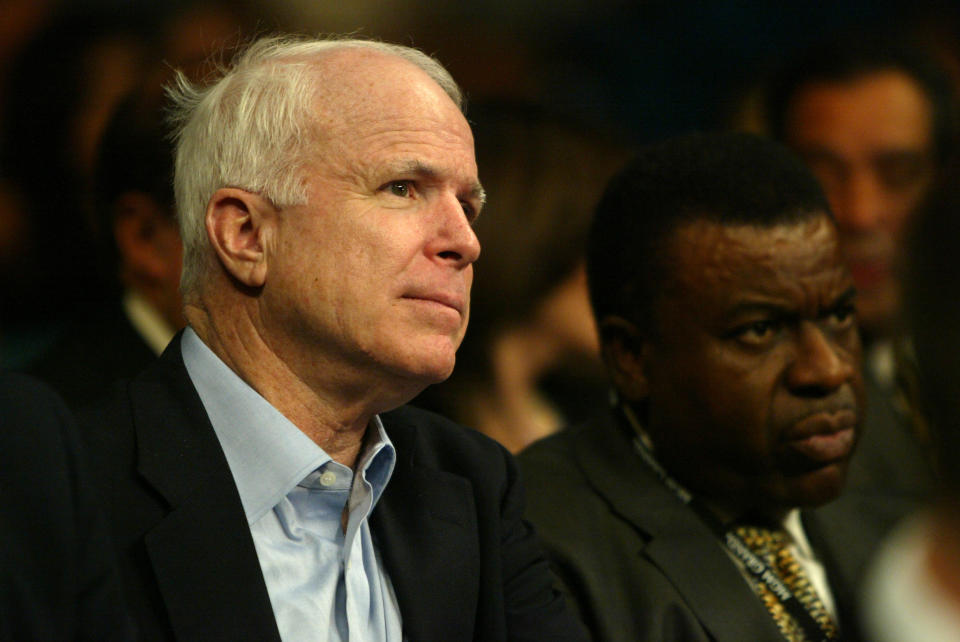

Sen. John McCain’s love for boxing was deep and abiding. Whenever his schedule permitted, the late Arizona Senator would be at ringside watching the major bouts of the time.

The Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act, that was signed into law by President Clinton on Jan. 24, 2000, was the result of tireless work by McCain and a few other senators hoping to help boxers they saw as exploited and powerless.

The Arizona Republican died Saturday at 81 following a lengthy battle with brain cancer. McCain befriended boxing promoter Lou DiBella in the mid-1990s when DiBella was an executive at HBO Sports charged with putting on boxing matches. They worked side-by-side on the landmark Ali Act and remained friends until McCain’s death.

“He loved boxing and he wanted to make it better,” DiBella said. “Everything that went on, it frustrated the [expletive] out of him. Ali was one of his heroes. It’s no accident that it’s called ‘The Ali Act.’ He hated bad judging. He hated to see boxers exploited. At the time [the Ali Act was being debated], there were some scandals with the rating organizations and that troubled him. He hated all the stuff that real intelligent, hard-core, caring fans hated. He hated it. He absolutely hated all of the nonsense. He wanted to see boxing be better and he had so many things on his plate, he couldn’t do what he really wanted.

“But he loved sports and he really had a passion for boxing. He loved the mentality the fighters had and he just loved to sit and watch a great fight.”

McCain was not only hugely passionate about boxing, he used his influence to make it better for those at the bottom of the totem pole. The general perception of him, though, is that he tried to drive mixed martial arts out of business, but that doesn’t recognize the full story.

In 1997, he appeared on Larry King’s show on CNN with Marc Ratner, then the executive director of the Nevada Athletic Commission and now an executive with the UFC; as well as fighter Ken Shamrock. In the early days of the UFC, there were only three prohibited moves: No biting, no eye strikes and no groin strikes.

McCain infamously referred to MMA as “human cockfighting,” and used his influence to have it removed from television. It almost did the sport in. But his words and actions were out of a sense of trying to help the fighters.

When in the late 1990s MMA promoters began to seek out regulation, McCain approved. And ex-UFC owner Lorenzo Fertitta, in a statement to Yahoo Sports, said the sport may not exist now were it not for McCain’s insistence on regulation.

“If it wasn’t for Senator McCain forcing the issue of regulation in MMA, the sport wouldn’t exist and flourish as it does today,” Fertitta said. “Once he felt that health and safety issues were being addressed for the fighters, he had no issue at all with the sport.”

McCain lent his support to actions which supported MMA fighters once the unified rules were passed by New Jersey in September 2000. On April 26, 2016, he appeared at a news conference in Washington, D.C., to support the Cleveland Clinic’s brain study of professional fighters.

Among those who attended were Bellator MMA president Scott Coker, boxers Larry Holmes, Paulie Malignaggi and Austin Trout and MMA fighter Phil Davis. Ex-NFL star Herschel Walker, who briefly fought MMA, also attended.

“Senator McCain was good for MMA because back when he made those ‘cockfighting’ remarks, MMA was in its early stages and was marketed as such,” Coker said. “By drawing attention to this, Senator McCain forced the industry to evolve through rules and regulation and helped to turn it into the sporting competition that it is today.”

McCain loved the competition, but wanted to make certain the fighters were protected as well as possible.

DiBella said McCain favored a national boxing commission, but one never came close to being created. He worked on the Ali Act to try to fix some of the most egregious problems that a national commission would have attacked.

“The driving force [behind the Ali Act] was a real feeling that fighters were too easily exploited and that there needed to be regulation over the big conflicts of interest in the sport,” said DiBella, a long-time Democrat who worked on McCain’s 2000 presidential campaign. “He felt boxing had a lot of problems that needed to be fixed. He got it completely. He got it more than just about anybody in terms of the bad judging and the conflicts of interest and the inadequate medicals and the toll that could take on the athletes physically and the economic exploitation that had been tolerated in the industry.

“He used his position as a great American hero, a wonderful statesman and a powerful politician, to speak up for those who really didn’t have a voice. He tried to give voice to the voiceless and make a sport he loved better for those who for so long got the worst of it from every angle.”

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports