Is it really an honour for a Black athlete to win an award named after Lou Marsh?

This is a column by Morgan Campbell, who writes opinion for CBC Sports. For more information about CBC's Opinion section, please see the FAQ.

By Wednesday afternoon we'll have crowned Canada's best athlete for 2021, with the Lou Marsh Trophy going to the winner.

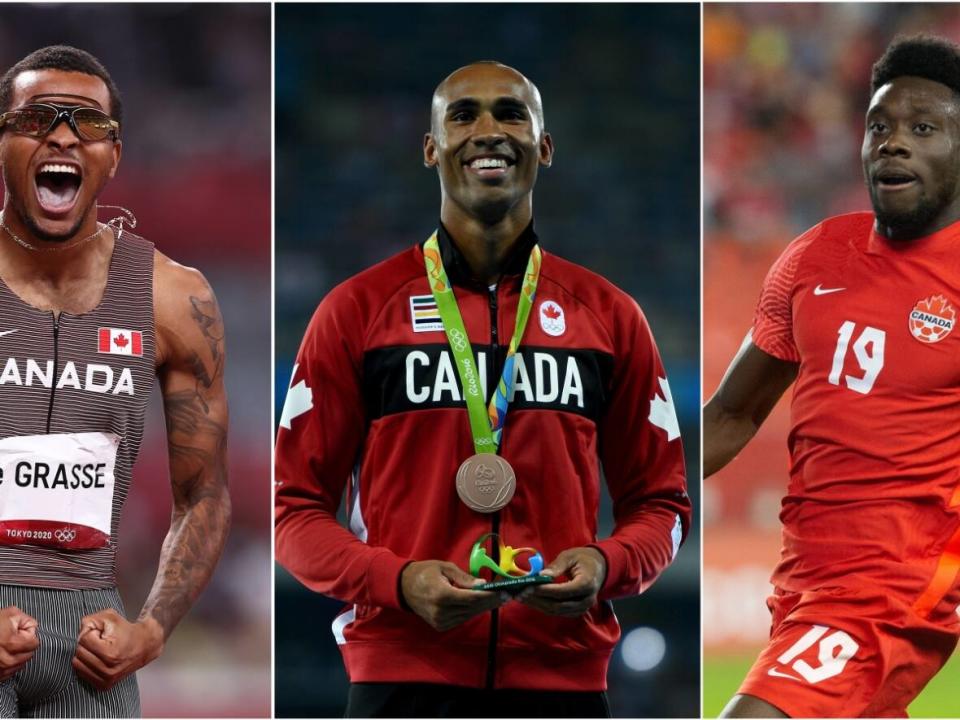

Leading contenders include Andre De Grasse, who set a national record to win 200-metre gold at the Summer Olympics in Tokyo, and who finished the Games with bronze medals in the 100 metres and 4x100 relay.

Or the trophy could go to Damian Warner, who won his first Olympic decathlon gold medal in Tokyo. He opened that competition with a 10.12-second 100m, the fastest ever run in Olympic decathlon, and closed with a 4:31 in the 1,500m, a feat of endurance that should be impossible for somebody with Warner's raw speed. He's like a Chevrolet with a Corvette's speed and a Volt's fuel mileage.

And there's Alphonso Davies, who shared the award with NFLer Laurent Duvernay-Tardif last year, and who remains the best player on a Canadian soccer team that currently leads CONCACAF World Cup qualifying.

If you're wondering how Marsh, longtime sports editor of the Toronto Star, would react to the trophy bearing his name landing in the hands of a Black person, it's a fair question. Along with his jobs as journalist and all-purpose referee — hockey, boxing and wrestling — Marsh had a history of littering his copy with racist comments. Some of it, at the time, was run-of-the-mill, early 20th-century bigotry that didn't sound offensive to contemporary ears, in a city less diverse than it is today.

WATCH | De Grasse wins historic gold in men's 200m at Tokyo 2020:

But Marsh's late-career antisemitism is tougher for modern audiences to rationalize. He referred to boxer Sammy Luftsping as an "aggressive Jew Boy," and refused to acknowledge the deadly menace Nazi Germany represented in the mid-1930s, when the rest of the world was choosing sides.

When Canadian sports writers first started voting on the award, its title an honour to Marsh, his track record on race didn't matter. But these days, it does. The last year has seen a growing chorus of voices calling to rename the trophy we hand to Canada's top athlete.

Add mine to it.

Not because I want to put a nail in what Aaron Rodgers might call Marsh's "cancel culture coffin," or think he deserves to be written out of history. Marsh was a towering presence on Toronto's sports scene. There's no changing that reality, and no need to. He'll always have a place in textbooks and archives, and on Boxrec, where you can examine his entire two-decade career as a boxing referee.

But the trophy needs a new name because of progress. Not passive, but hard won, by successive generations of civil rights leaders and everyday citizens who have worked to make Canada the multicultural country we currently inhabit. As a sports community, we can honour that ideal by naming the trophy after somebody whose legacy aligns more closely with the values we, as a nation, say we cherish.

I say that knowing how difficult it is to reach across eras to compare types and degrees of racism.

WATCH | Warner offers event-by-event breakdown of his decathlon gold:

Marsh once described legendary distance runner Tom Longboat as "smiling like a coon in a watermelon patch." This particular smear, one of many Marsh lobbed at Longboat over the runner's career, is equal parts offensive and efficient. In using a well-worn anti-Black trope to insult an Indigenous runner, Marsh hits his target and ensures collateral damage.

But he wrote those words in 1909. Thirteen years before that article, a ragtime piece called All Coons Look Alike to Me, was one of the most popular songs in America. Six years later, The Birth of A Nation, which depicted the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and portrayed the terrorist group as heroes, packed movie theatres on both sides of the border.

Against that backdrop, to contemporary readers, Marsh's racist comments about Longboat were less egregious than mainstream. If you're looking to extend the benefit of the doubt to Marsh, you could read his words in the context of the flagrant racism in everyday media, and label him a product of his time.

You could also point to his work as a boxing referee, where he couldn't ignore the sport's colour line. Toronto-based heavyweight Larry Gains held the Commonwealth title, and the world Colored championship, but could never challenge for the mainstream world title because of a gentlemen's agreement that kept those bouts all-white. Between 1926 and 1929, Marsh refereed 10 of Gains' bouts, against both Black and white opponents. Gains won all 10, suggesting Marsh and the judges treated him fairly.

The wrong side of history

But it's tougher to categorize Marsh's antisemitism as a simple product of his era. In the leadup to the 1936 Olympics, he criticized Canadian athletes who, uneasy about helping Nazi Germany launder its public image, pondered a boycott of the Berlin Games. He also downplayed the Nazi regime's inhumane treatment of Jewish citizens, dismissing it, as "an internal German matter."

Even back then, folks knew who the villains were in this scenario. European and North American powers were already choosing up sides in the leadup to what would become World War II. Of all the groups who could have used an ally in the North American press, the Nazis weren't one. Most people understood it then, like they understand it now.

WATCH | Davies's scintillating solo effort healps lead Canada past Panama:

So when academics like Western University professor Janice Forsyth, and veteran sports broadcasters like Mark Hebscher and Gord Miller, say the trophy needs a new name, they're not just talking. They're acknowledging the need for a rebrand more aligned with current values.

Hebscher suggests calling it the Terry Fox Trophy. If you're asking me to brainstorm names, I'll co-sign on Fox, and also offer Longboat, a trailblazer who deserved better press, or Barbara Ann Scott, the first woman to win the trophy.

Sometimes updating traditions beats honouring them unchanged. Cleveland's MLB team did it. They dumped their racist caricature of a logo, and, whenever play resumes, they'll take the field as the Guardians.

Decades before my brief career as a college football benchwarmer, my school, Northwestern, and our in-state rival, Illinois, played for the Sweet Sioux Trophy — a carved wooden figurine of a Native American. Quickly, the trophy got downsized to a tomahawk, which we won the two years I patrolled the sidelines.

By 2009, both schools agreed that the tomahawk's racist imagery was insulting and outdated, so they replaced it with the Land of Lincoln Trophy, in the shape of the stovepipe hats Honest Abe wore. This year, Illinois claimed the prize with a 47-14 win. My wife is still celebrating, while I'm coping with loss. But even in our divided house, nobody misses either iteration of the Sweet Sioux. The transition was inevitable. You either like it or you learn to.

So practice saying "Terry Fox Trophy" or something similar. Say it till it sounds good, and eventually you won't miss Lou Marsh.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports