R.F. Kuang Is Not Your ‘Cultural Tour Guide.’ She’s a Storyteller

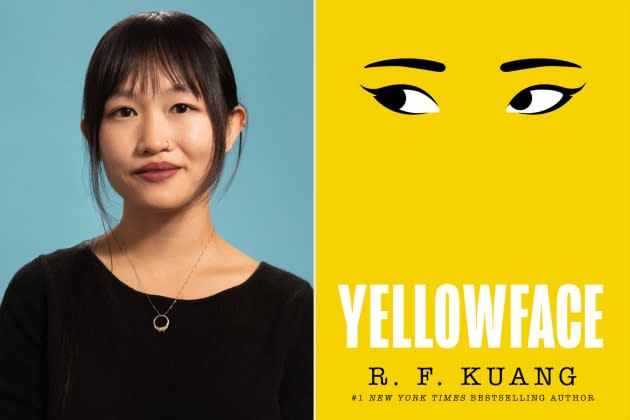

THERE ARE A FEW obvious reasons for author R.F. Kuang to be drinking before 5 p.m. on a Friday. She’s just turned in the last paper of the semester for her Ph.D. She’s on Day One of a monthlong national book tour. And her new novel, Yellowface, which debuts Tuesday, is on track to be (another) bestseller.

Sitting with her editor at a hotel bar in Manhattan’s East Village, the scene ironically mirrors the last bit of normalcy Yellowface begins with. That is, before the book — and its main character, June — take a nosedive into chaos. Yellowface follows the exploits of jaded novelist June Hayward, a white writer who is failing to thrive at her chosen career. But when a freak accident kills literary “rising star” (and her nemesis) Athena Liu, June steals her manuscript and ethnicity, eager to have the fame she believes she’s always deserved.

More from Rolling Stone

'The Other Two' Stars Talk Roasting Hollywood (and Rolling Stone!) in Season 3

Protesters Occupy Ron DeSantis' Office in Opposition to Anti-Diversity Bills

Kuang published her first book, 2018’s The Poppy War, at age 19. She became a Number One New York Times bestselling author while studying history at Georgetown University (she followed that with master’s degrees at Cambridge and Oxford, and is currently completing the Ph.D. in East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale).

“The Ph.D. is very different monster,” Kuang tells Rolling Stone that afternoon at the hotel bar. “The worst part of being a successful writer is that it takes away all the time you have to actually write. I’m looking forward to all of this dying down so I can just be alone with the page again.”

Yellowface is the first caustic satire for Kuang, who is known for her transformative fantasy works. Reading it feels like you opened a Dickens novel that turned out to be a snappy Colleen Hoover thriller. But it’s a purposeful vibe shift from an author whose biggest fear seems to be doing the same thing twice.

“Whatever I’m working on at the present, like each new book, is my [favorite work],” Kuang says. “I’m like, ‘This is my magnum opus. Everything else is trash.’ It makes it really hard to talk about my back list. But it’s constant growth and transformation. You just can’t spend that much time looking back.”

The story builds on itself really quickly. How do you combine that consumption speed with such a serious topic as representation and racism in the publishing industry?

There is a clash between the style and the subject matter. The style is painting with very quick, sloppy brush strokes. And the characters themselves do this — they judge the world with these very sloppy declarations. At the same time, there are all these really knotty issues of authenticity, identity, the commodification of race, and what happens when we turn race into a marketing label. The text can’t really offer solutions, and it certainly shouldn’t offer clear moral standards. The best way to use this style is to make everything as messy as possible, crack open the question, and illuminate everything that’s at stake.

You’ve talked about Athena as a cultural broker, a translator-type character who builds bridges of understanding between groups. How has your understanding of these brokers changed as you’ve grown into who you are as an author?

When I started drafting Athena and figuring out who she was, why she’s so obnoxious, I didn’t immediately light on the fact that it’s because she is a cultural broker. But as the manuscript took shape, it became obvious that the reason why she’s so threatened by other Asian American writers is because she fulfills the function of that Asian American who explains Asian Americans to white people.

My attitude to being perceived this way has changed a lot since I got started in publishing, because when I was 19, I was just happy to be there. I didn’t really care how people talked about me. At least people care about my family’s history. At least people cared about the content of the novel. But over time, I’ve gotten more and more impatient with the idea that marginalized writers exist to educate everybody about their marginalization — that Black writers exist to tell people how difficult it is to be Black, or that the only kind of story that I’m capable of writing is an Asian-immigrant trauma story. We’re not ethnographers. We’re not cultural tour guides. And I’m not teaching a seminar on Chinese American history. I’m just a storyteller, and I want to be read on the strength of my storytelling.

Did it feel meta to publish a book that’s a middle finger to publishing?

This is not a book that you could publish as a debut, in part because a debut writer just doesn’t really know what they’re getting into. I couldn’t have made up how ridiculous the industry is, because whatever your imagination is, somehow the reality is worse. It took all those years of being on the receiving end of people like June to be able to consolidate them into a story that then turns around and skewers everybody. My agent didn’t want to submit Yellowface to anybody. She was so scared that it was going to burn bridges, and that people would get pissed off and wouldn’t want to work with me anymore.

And I think that’s what made it possible to work on this book with the team. Because even though publishing writ large is really fucked up, there are people in the industry who are still there for love of the story and the authors. That’s why they aren’t taking jobs with much higher salaries somewhere else. Working on this manuscript felt like everybody was on demon time. Like, “Fine, let’s lean all the way into this. Let’s examine ourselves and make fun of every single thing we’ve done.”

I’m sure tackling your frustration was cathartic.

Writing it was super cathartic, and then turning in the final draft, I felt like I’d finally let something go after years of people telling me, “You’re only interesting because you’re Chinese American and you’re a token,” and, “The only reason why you have the audience you do is because you tick off a diversity checklist.” I know it’s all silly and irrational, but when you hear it often enough, you start wondering if it’s true. And in writing Yellowface, I was finally confronting that voice head on and trapping it on the page.

You participated in the HarperCollins strike. Why was it important for you to be there, especially with workers picketing the people who publish your books?

I don’t know any authors who thought twice about supporting the strike. Or if I do, they’re not my friends. Because all the things that authors complain about — edits being late, not getting enough marketing attention, people not responding to their emails — that is reflective of a workplace where there are too few people working too many jobs, being assigned too many tasks, and not being paid a livable salary. So it’s obvious that if we want conditions for authors to be better, it starts structurally at the publishing house.

Writing one great book is hard enough, and you’ve written five. Do you ever feel pressure to live up to the success?

I would feel nervous if I was still writing the same fantasy series. And some of my favorite writers do this, so it’s not a knock on that career. But every new project has to be a creative challenge for me, and you have to become a different person in order to meet that. My life is going to be a series of transformations and experimenting with increasingly weird stuff. So rather than feeling restrained by my current body of work, I feel very emboldened to pursue the weird stuff I wouldn’t have dared attempt if I didn’t have, you know, these five novels as training wheels.

I might fall flat on my face, and it might not work. But that wouldn’t disappoint me, because then at least I tried something other than repeating previous successes. I think constantly about how to get back to that first moment of falling in love with the work. So the philosophy I’m taking with me is: Everything has to be new.

Best of Rolling Stone

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports