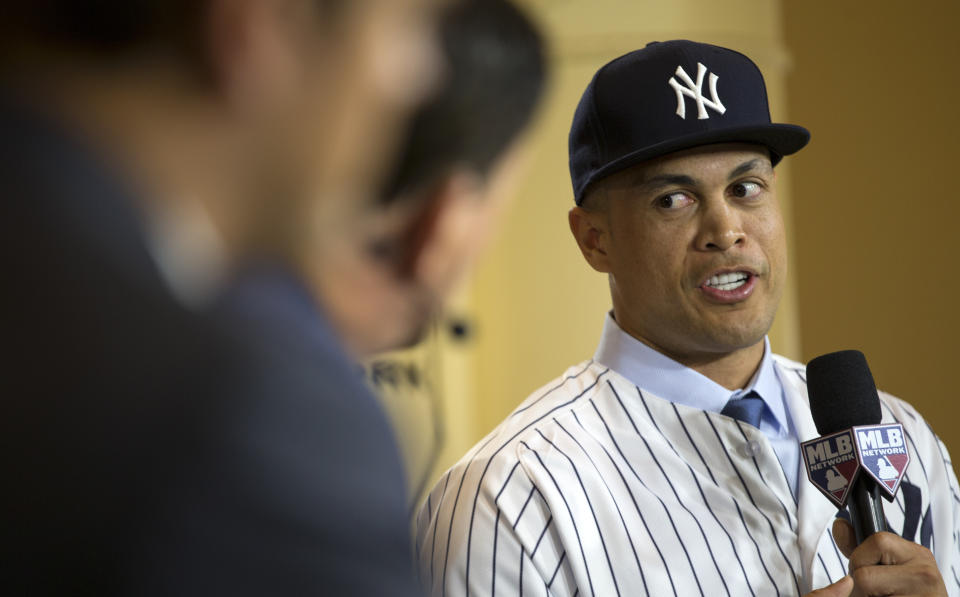

The questionable treatment of Giancarlo Stanton was Derek Jeter's latest blunder

LAKE BUENA VISTA, Fla. – No matter what Derek Jeter says, how he tries to spin his Miami Marlins’ pennies-on-the-dollar trade of Giancarlo Stanton to the New York Yankees, the truth is nakedly evident in his franchise’s actions. From the moment he and his partners plopped down $1.2 billion to buy the Marlins, their deeds have screamed bush league. This is what it looks like when amateurs try to play-act as professionals.

On Monday, as the Stanton trade became official and the Marlins set the GPS for their immediate future into the pipes of a toilet, Jeter said on a conference call: “There isn’t anything I would have done differently.”

Really? Nothing? He wouldn’t have given Stanton the courtesy of a phone call in his first two months as owner – something that no player is owed but one with a $295 million commitment is given because it’s prudent as a person and a business owner? He wouldn’t have reconsidered the team’s threat to Stanton that if he didn’t accept a trade to the St. Louis Cardinals or San Francisco Giants, he’d be a Marlin for life – or at least until he could opt-out after the 2020 season – which was the equivalent of a 7-2 off-suit bluff against pocket aces? He wouldn’t have tried to get more for the 59-home run-hitting reigning National League MVP than Starlin Castro and two prospects, one a soon-to-be 22-year-old who hasn’t pitched above short-season Class A ball and another who’s an 18-year-old rookie-ball lottery ticket?

Either Jeter believes that and is worse at this than anyone realizes or he’s trying to talk his way out of a moment that grew too big for a neophyte and collapsed on him. Because the truth of it is, one sin of which he’s being accused – trading Giancarlo Stanton – wasn’t a sin at all. For the Marlins to dig out from the disaster left behind by Jeffrey Loria, the team’s previous owner, the pragmatic move was to deal Stanton, use the heft of his 2017 season to reload a bereft farm system and sell off every other worthwhile piece and part for a full-fledged tank job.

Along the way, even as the Marlins lost, they could have built up goodwill through their treatment of people, their commitment to becoming a first-class organization. Instead, they are the team that calls a scout to tell him his contract won’t be renewed as he’s lying in a hospital after cancer surgery. They are the team that lets go of well-liked ambassadors and popular announcers with a connection to the fan base. They bungle the easy stuff, which makes their handling of Stanton’s situation no surprise. They have taken on the herculean task of making Loria look OK by comparison with impressive aplomb.

And so to see Stanton on Monday throw more shade than a pergola didn’t exactly take those who know him well as a surprise. For years, he has languished in Miami hopeful something would change. He signed a 13-year, $325 million contract extension, the richest in American sports history, with the hopes that the organizational vines would climb him as a pillar. Among him, Christian Yelich, Marcell Ozuna, J.T. Realmuto and Dee Gordon, the Marlins had an envious core. They lacked pitching. When he finally spoke with Jeter, Stanton asked if the team would consider shelling out for some. The answer was no. He wanted no part of that. It’s difficult to blame him. The Marlins started shopping him to the Yankees, Los Angeles Dodgers, Chicago Cubs and Houston Astros, the four teams for which he said he would waive his no-trade clause. None bit.

Only recently Jeter “relayed to him we wanted him to be a part of the organization,” which doesn’t seem particularly true. If Jeter ever had any intentions of keeping Stanton, wouldn’t he have called? Welcomed him? Said he looks forward to building franchise around him? Told him that he understands the frustration but wants to develop something the right way, not in the haphazard, slapdash was of the old Marlins? Asked for time? Made an effort?

Stanton stayed above board anyway. Rather than outright reject the Marlins’ overtures to the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants about trading for him, Stanton met with both teams. He approached a toxic situation in a judicious and open-minded fashion. Neither fit his desire for a destination, in part because his calculation that later was proven correct: Without St. Louis or San Francisco in the mix, the Marlins – desperate to dump his deal – would re-engage with the teams he sought in the first place.

The accept-this-trade-or-you’re-stuck-with-us sham the Marlins trotted out was one last insult that Stanton happily swatted aside. “You’re not going to force me to do anything, regardless of what the situation is,” he said, and, funny enough, in the end he’s the one who forced the Marlins into a deal in which they accepted far less than their initial ask of the Yankees’ top prospects.

And even if Guzman grows into a major league starter and Devers an everyday shortstop, and even if Stanton collapses and his contract looks like an albatross – all possibilities, the game being what it is – it doesn’t lessen the short-term burden on the Marlins, who are barreling toward the bottom of the National League East, a place on which they may as well put a down payment. A chop-shop major league team and barren minor league system does not make for a winning franchise. If the Marlins are in as much financial trouble as they let on – FanRag reported they’re already seeking $250 million in investment capital – then a full teardown at least would allow them to pay down their debt for a time when the foundational elements to win do exist.

When asked what advice he might give to distraught Marlins fans, Stanton said: “Hang in there. They’re hurting. They’re going to go through some more tough years, but I would advise them not to give up. Just keep hope. Maybe watch from afar if you’re going to watch.”

Any turnaround will start at the top. And this much is true: Derek Jeter can be a good owner. He can learn from his mistakes, apply his intelligence – social, emotional, baseball – and thrive. Miami is an exceedingly difficult market for baseball. Jeter is in his infancy as an owner, and to judge his long-term fitness based on three rough months is unfair.

Rebuilds are hard. They can get ugly. They can make smart people do dumb things. They can take someone like Derek Jeter, he of the immaculate reputation, of two pristine decades as a New York Yankee, and place him in the middle of a mess that is far from entirely of his making but is now his burden to shoulder.

“We are trying to fix something that is broken,” Jeter said.

A mess this big will take years. And as time goes on, as the Marlins begin to remake themselves in Jeter’s image, perhaps they’ll learn the things they don’t know are more important than the ones they think they do.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports