Qualified immunity divides lawmakers in police reform talks. What is that legal defense?

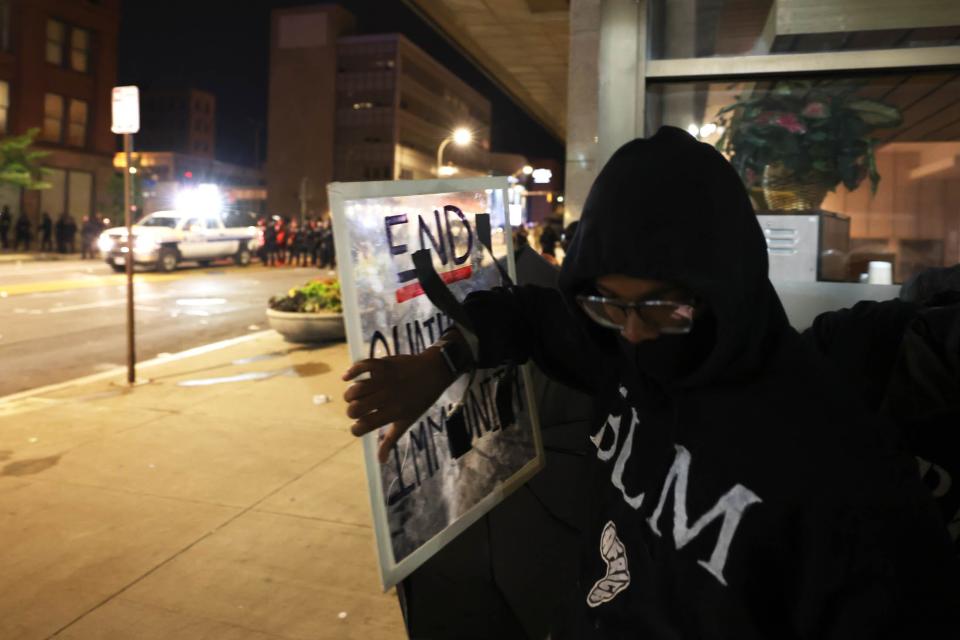

WASHINGTON – A year after the largest protests for racial justice in a generation, lawmakers in Congress are still debating police reform.

Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., said Tuesday that while he is "hopeful" about reaching a deal, it will be "very hard" to reach a bipartisan agreement before the end of June, when Congress enters a two-week recess.

While negotiators have come together on a range of policies, a key legal point divides Democrats and Republicans: qualified immunity, a provision that shields government employees from lawsuits while on the job, especially for police.

“The short answer is, the immunity issue is still very important,” Scott told CBS News. “But the body of the George Floyd bill versus the Justice Act – there’s a chasm between the two," he cautioned, noting that the divide was “a little more complicated than just the top four or five issues."

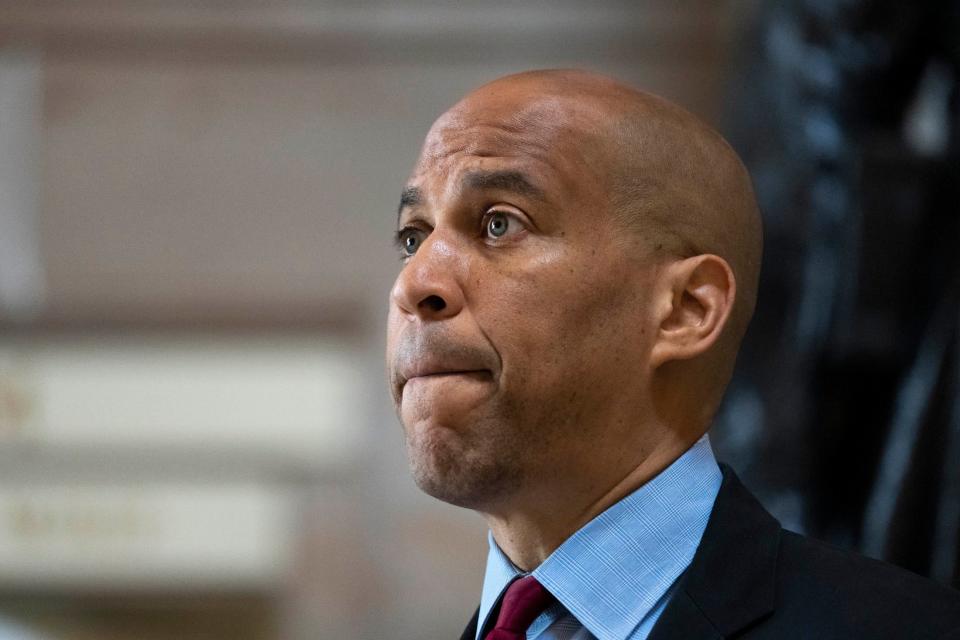

While Scott emphasized that lead negotiators have been able to bring their proposals "very close together," his talks with Rep. Karen Bass, D-Calif., and Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., may be thwarted by an issue seen as nonnegotiable.

Understanding what qualified immunity is and how it is driving the negotiations is key to the future of policing in the U.S.

What is qualified immunity?

Qualified immunity is a legal provision that protects government officials from being held personally responsible for potential on-the-job misconduct or unconstitutional actions. It does not apply in criminal cases.

The Supreme Court introduced the doctrine in 1967 for law enforcement officers who were acting in "good faith."

Its current form traces back to the court's 1982 ruling in Harlow v. Fitzgerald, when the court determined that "objective terms" were necessary to find whether misconduct warrants individual punishment. Specifically, the court determined that a person could successfully sue a government official only if that person violated "clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known."

That effectively altered the acceptable standard for lawsuits brought under a federal statute – originally created to help the government fight the Ku Klux Klan after the Civil War – which said only that a government official who violated someone's rights "shall be liable to the party injured."

The doctrine also applies only in cases in which it can be determined that a state agent did infringe on someone's federal rights, but the right in question is not "clearly established," according to the 1982 ruling.

Police reform advocates: Standard is too high to beat qualified immunity

In practice, qualified immunity frequently stops civil cases of misconduct from being brought against government officials, most often police. Plaintiffs are usually required to find a case similar enough to their own to show that the right being violated was "clearly established," a bar that many argue is too high.

"Something can be very abusive, but if you can’t find a court decision that finds it as such, then the qualified immunity stands. I think that this doctrine has really become overly broad, and I don’t think that there was ever a strong basis for it. ... It’s been expanded in ways that I think are very harmful," said F. Paul Bland Jr., executive director of the legal advocacy group Public Justice.

Many advocates also express frustration at the expansion of qualified immunity over time.

"It has only become interpreted more and more broadly. It has become harder and harder to bring a suit against a police officer who has violated someone’s rights because of the expanded view of the doctrine," said Jami Hodge, the director of Reshaping Prosecution at The Vera Institute of Justice.

Importantly, critics of qualified immunity believe the doctrine incentivizes bad policing. The only way to ensure accountability for officer misconduct and abuse is to end the practice, analysts argue.

Eliminating qualified immunity "incentivizes police agencies to properly hire, train and supervise law enforcement to prevent abuses from occurring in the first place," said Rebecca Brown, policy director for the Innocence Project, a nonprofit criminal justice group.

"It’s a little perverse because for particularly egregious actions there may not be a previous case, whereas something a bit more run-of-the-mill may have precedent," said Chris Kemmitt, deputy director of litigation at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Opponents of qualified immunity also contend that the doctrine represses the types of cases that would later help bring a successful suit.

"Because police are unlikely to be charged and even more unlikely to be convicted under criminal charges, what you are left with is civil lawsuits. And then if the Supreme Court comes in and puts their thumb on the side of law enforcement in those cases, it becomes even harder to see a successful conviction," Kemmitt said.

Since last summer's historic protests for racial justice, police reform activists have seen some progress in ending qualified immunity.

In June 2020, Colorado became the first state to ban qualified immunity in legal proceedings, followed by New Mexico in April. New York became the first major city to end qualified immunity for police officers. Connecticut also has taken some significant steps in curtailing the legal doctrine.

Lawmakers in 16 states are pushing to either end or limit qualified immunity, according to Innocence Project data.

While those efforts have received praise from activists across the country, reformers are also clear that there is no substitute for federal action, preferably from Congress.

"I think it's really important that states are taking these steps, and they should take these steps, but at the same time qualified immunity is a federal legal doctrine," Kemmitt said.

In Congress, Democrats are pushing to end qualified immunity as part of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which would also enact a series of policing changes that lawmakers argue would increase accountability.

“Qualified immunity is not a law, it is a court decision that has been wreaking havoc on courtrooms around the country for years,” Bass, one of the lead Democratic negotiators, told The Washington Post in May. “This is something that has needed to be resolved for a very long time. Now is our opportunity to do that.”

Qualified immunity supporters raise concerns over prosecution

Defenders of qualified immunity argue that making police officers liable for misconduct would hamper their activities, especially when split-second decisions are needed.

Qualified immunity "does not shield officers from criminal misconduct, and it does not shield officers who knowingly violate someone's rights. But if an officer in good faith violates someone's rights and didn’t even know that right exists, for instance, then in a situation like that the Supreme Court said it's not a part of American jurisprudence to hold a person liable for a situation," said Bill Johnson, executive director of the National Association of Police Organizations.

Police groups argue that accountability exists in other forms and that cases like the criminal prosecution of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin were not ultimately influenced by qualified immunity.

Johnson also said ending qualified immunity would be damaging to police morale and recruitment, which have already been low after a year of calls to reimagine American policing.

"I think to the extent it changes behavior at all – if qualified immunity were taken away and if there were a raft of monetary penalties against officers – it would change things in that it would make people say, ‘I do not want to do this work as a cop, and I’m going to find an easier job elsewhere,’" he said.

"You’re much more likely to get the proper result that you want through correct training and giving positive reinforcement for when they’re doing the right thing as opposed to punishment."

Aware of the low trust and antipathy many communities have toward law enforcement, some police groups are receptive to policing reforms and accept that qualified immunity is a part of that conversation. But law enforcement organizations are clear that any new policies shouldn't burden rank-and-file officers.

"The intense debate over qualified immunity protections for police and the difficulty in resolving it stem from a broader crisis of trust and public outcry for accountability, although qualified immunity is available to state and local government officials beyond the police," said Jim Burch, president of the National Police Foundation, a nonprofit group that advocates for improved policing through innovative policy and technology.

"Though it was created within the judiciary and though this debate may be about much more than the doctrine itself, we believe that opportunity exists to clarify key aspects of qualified immunity doctrine such as 'clearly established law'," Burch said, arguing that change was possible "without entirely eliminating appropriate protections for difficult jobs that may expose individuals to litigation, even in the absence of malice or malfeasance."

Most police organizations are opposed to large portions of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

"From what I’ve seen thus far from Sen. Booker, its just a mishmash that kind of massages last year’s (George Floyd Justice in Policing Act) and kind of changes superficially some of the language, but it's not something that a group like us could support at all in its current form," Johnson said.

"We have grave concerns about the current draft,” Jonathan Thompson, executive director of the National Sheriffs Association, told Politico. “However, we remain open to the possibility that something balanced and reasonable is achievable."

With lawmakers openly contemplating ending the legal doctrine, some police groups argue that it is time for Congress to codify the legal defense into law.

“It is almost impossible for an officer to determine how a legal doctrine will apply to a split-second factual scenario,” Patrick Yoes, national president of the Fraternal Order of Police, wrote in a letter in February urging Congress to make qualified immunity into law.

“Thus, unless there is existing precedent that squarely governs the facts before the officer, the reasonable officer needs to be afforded a certain degree of discretion to make split-second decisions in situations that could put lives, including their own, at risk."

Representatives from the Fraternal Order of Police declined to be interviewed for this story.

"We have discontinued the policy of talking to outlets where we have to pay a fee to see how we are quoted," a Fraternal Order spokesperson said.

The future of qualified immunity

Sen. Scott, the lead Republican negotiator on police reform, has consistently said individual police officers should not be held liable, though he has expressed openness to reforming the provision.

"The more you dig into the bill, the more there is to talk about," Scott told reporters on Monday.

He has signaled openness to making police departments liable for misconduct claims while still shielding individual officers.

Drafted legislation leaked to Politico showed that lawmakers were moving in Scott's signaled direction, with the latest bill stating "the public employer of that officer shall be liable to the party injured for the conduct of the officer in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress."

The text also would make it illegal to use excessive force if the agent "knows" or "consciously disregards a substantial risk that the force is excessive."

“Qualified immunity is a problem. It’s a pretty simple solution: Don’t sue the police officer, sue the department,” Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., Scott's co-senator from the Palmetto State, told Fox News in April.

“If you want to destroy policing in America, make sure every police officer gets sued when they leave the house.”

Some Democrats remain skeptical that such a measure would be effective in curtailing police misconduct.

"We compromise on so much. You know, we compromise, we die. We compromise, we die," Rep. Cori Bush, D-Mo., told CNN in April. "I didn't come to Congress to compromise on what could keep us alive. ... If you don't hurt people, if you don't kill people, if you are just and fair in your work, then do you need the qualified immunity anyway?"

U.S. Supreme Court has ruled recently on qualified immunity

The Supreme Court has also indicated it may revisit the scope of qualified immunity soon. In November, the court overturned a ruling that protected Texas corrections officers from a prisoner's lawsuit that alleged he'd been kept in "shockingly unsanitary" conditions.

"Confronted with the particularly egregious facts of this case, any reasonable officer should have realized that Taylor’s conditions of confinement offended the Constitution," the court wrote.

In February, the court similarly ruled that the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals should reconsider a case where it upheld qualified immunity. Some legal analysts argue that the rulings from the court may foreshadow a complete re-thinking of qualified immunity, though others point out the cases in question may merit extreme circumstances.

Follow Matthew Brown online @mrbrownsir.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Qualified immunity, explained: Behind the legal shield for police

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports